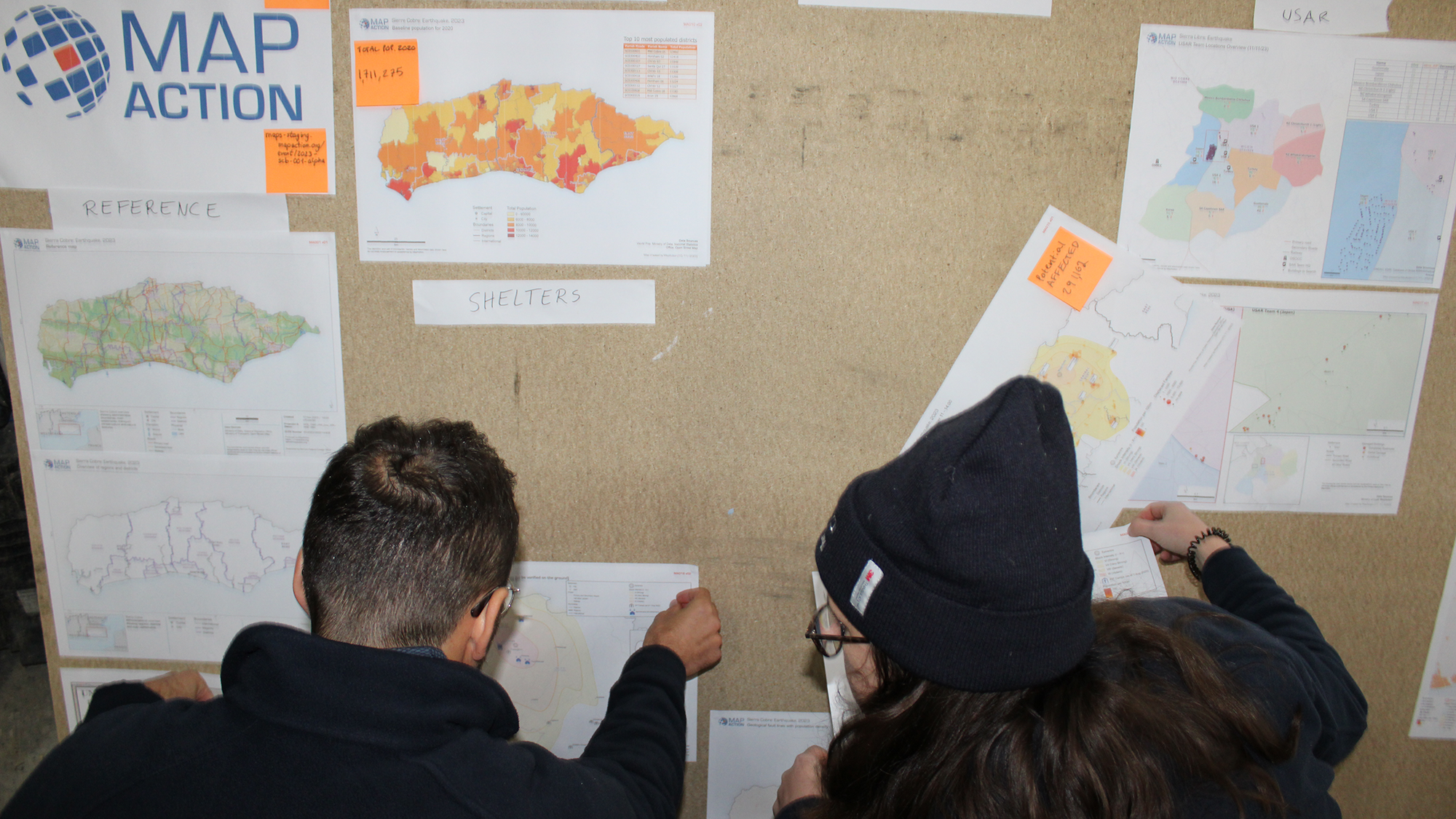

MapAction team photo, after disaster simulation exercise, Peak District, 2024. © MapAction

Land Journal: Can you tell us how your career led you to become chief executive of MapAction?

Colin Rogers: When I finished my master's in applied parasitology and medical entomology at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was working on a parasitic disease outbreak in what is now South Sudan. I got a job that involved some field experience in 1995.

The work involved going out with a global positioning system (GPS) and plotting vegetation, identifying forests where the transmission of this disease was known to take place. This enabled MSF to work out where to locate treatment centres.

I started in the front line of a civil war in Sudan and carried on doing deployments in such situations for around 16 years, leading the response to humanitarian crises for various agencies. I was moved to see the level of humanitarian need, how children and their families were suffering through no fault of their own. I wanted to use my skills in parasitic disease diagnosis to help reduce the suffering and ensure people got the treatment they needed.

After that I moved back to headquarters roles where I was in charge of different organisations' global humanitarian operations, advising national offices how to respond to future hazards and working on quality standards for humanitarian agencies.

The standards also provide a benchmark for agencies when planning, for example, how much water a person requires per day, informing their operational decisions. They also mean all agencies are working to a common benchmark, developed by technical specialists to support wider humanitarian work. Then the position at MapAction came up.

Since joining in October last year, I have been struck by the power of data in the humanitarian sector at a time when the number of people who need help, whether they are currently affected or at risk of a future crisis, is at an all-time high.

The funding requirements, according to the UN, just to keep people alive for this year are huge – $48.7bn. We're seeing increasing impacts from disasters on large population groups owing to climate change, with the associated political instability and displacement of people.

LJ: What do you think are the capabilities of data?

CR: Having had a lot of experience on the ground, I had never fully recognised how much more could be done with data. For instance, reliable data can reduce the stress on operational staff when you are under pressure to make difficult decisions in the middle of a rapid onset disaster, such as the Asian tsunami in 2004.

At MapAction we are a technical agency working with senior managers in operational agencies who are making life-or-death decisions: we support them by providing the data they need. We work to open people's eyes to data and geospatial specialisms, showing generalists that they don't need to be analysts themselves because we can help them understand their data to inform better decisions.

At the start of an operation or a crisis response, that data might be quite limited and incomplete. The quality could be problematic and there may be discrepancies, but we can help with various phases through consultation: once data is sourced and processed, it needs to be calibrated because different values have different ranges and units, such as number of casualties, corruption index, immunisation rate or health facilities density.

To aggregate these on a single index they must be normalised – for instance dividing them all by the maximum for a country or region – and then expressed in a common format as a value between 0 and 10. Finally, the data is reviewed and validated with indicators verified and, where necessary, corrected.

As an emergency response progresses and more reliable data comes through, an organisation should be able to feel more confident in its decision-making process. We want to ensure life-saving assistance reaches those most in need, saving lives, while at the same time enabling organisations to communicate communities' needs to donors and secure the funding to target help more effectively. Good, early information management in a crisis can help do all of that.

With the right data, disaster authorities can get funds early by triggering anticipatory action and implementing mitigation measures. For example, when a river level gets to a certain point a warning is put out so people have time to evacuate, move school supplies to higher shelves, get to emergency shelters or elsewhere to reach safety. They can move their cattle away. Given enough warning people can save their businesses, belongings and lives. Although we can never reduce the risk to zero, risk modelling and looking at predictive analytics can minimise the effects of a crisis.

We've done a lot of work around emergency response. In the past 20 years, our staff and volunteers have responded to more than 140 emergencies worldwide, including more than 70 at the request of UN agencies. We've supported decision-makers in more than 30 responses to major floods and another dozen major earthquake responses.

Now we can take our skill sets and apply them more broadly across humanitarian work, looking at preparedness, early warning and anticipatory action. One thing we are focusing on is predicting future shocks and working out how best to mitigate their potential effects.

We are looking at risk modelling and identifying risks locally, which until now has been mainly done at a national level. If a national government or local civil society organisation for instance is aware that a crisis could put certain communities and livelihoods at risk, it needs data to support investment in preventing it happening. So we work with many organisations to help them prepare for future disasters to build such models.

LJ: What about artificial intelligence (AI)? Is that important in the sector?

CR: AI is a buzzword, certainly, but I would like to get the basics of data sorted first. More granular data for emergency responses that accounts for sex, age or disabilities can help local organisations make more nuanced decisions. We are particularly keen to bring women to the forefront of our work.

MapAction recently published an advocacy piece calling for more such data to be made available to humanitarian organisations during emergency responses, and AI may be able to help in the process of disaggregating original data.

LJ: How are things changing at MapAction?

CR: Our role is increasingly not to be on the ground ourselves but to be the trusted partner, to ensure data is used to give people early warnings so they can respond appropriately. We're also working with national and regional disaster management authorities so they remain responsible for decision-making.

We need to recognise that the sector can tap into the technical capability of geospatial visual specialists and data scientists around the world more effectively, so the products we develop work in the languages of affected countries instead of all being in English.

Humanitarian, UN or disaster management agency partners know that when a MapAction volunteer is supporting them, whether in an emergency response, a training programme or professional development scheme, they are getting people at the top of their game. MapAction volunteers include 11 people who work for government agencies and nearly a dozen academics, as well as tech and humanitarian leaders in the private sector.

At the same time as tapping into global expertise, we're no longer flying people around the world as much as we used to, both because of increasing climate consciousness and the shift towards using more local expertise.

If we have volunteers who speak the language – our volunteers speak more than a dozen between them – understand the context and can work with their local counterparts, and we can ensure a speedy response, we'll get involved. But deployment has to fit our strategy of increasingly supporting locally led responses.

During the aftermath of Hurricane Beryl in July, we had volunteers in the Caribbean who could deploy immediately and support emergency assessments and coordination, though we also deployed people from Europe. So we had five volunteers on the ground doing all the mapping for three countries, working with the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Authority to strengthen its leadership coordination.

We've got to support the first responders so they can lead and make decisions. We should only ever be coming in to provide an additional resource, giving national disaster management authorities the information they need to allocate resources and set priorities.

We saw this in Belize recently, in May, when there were wildfires. We had two volunteers working with the National Emergency Management Organization, providing the tools, listening to what data products and maps were needed.

The director of the national disaster management authority used our maps and analysis to brief the prime minister, senior politicians and civil servants. It would have been great if we'd had a national volunteer from Belize who could have done that, but we were at least able to mobilise technical, skilled resources giving the national disaster management agency what it was asking for.

Our service has to be of the highest quality because it enables directors of national disaster management authorities to take the necessary decisions to safeguard well-being in an emergency. Working with new partner organisations means we can embed new approaches, carry out peer-to-peer professional development and share our skills.

We can also link local organisations with their counterparts in other parts of the world. Regions can learn from each other's experiences of dealing with such issues.

After training with a national disaster management agency in the Caribbean, 2023. © MapAction

Volunteers completing 2023 Operation Readiness course before taking part in any emergency response. © MapAction

LJ: What skills do people working in the humanitarian sector need?

CR: You need to be a technical person but soft skills are also important. In this context, they're actually quite hard skills, such as diplomacy and communication.

If you're working with colleagues and English is their third or fourth language, you have to be mindful of that. When I'm recruiting I often look for people who have French and Spanish; but if they have Bahasa (Indonesian), Thai, Haitian Creole or Kiswahili for instance, that means we can work with many more people. Then there's cultural sensitivity. It's very easy for someone to come in and upset people by wearing shorts to the office or even by the way they eat.

You don't want to be seen as the specialist coming in, but as an additional resource for those who have asked you to be there to share your skills.

LJ: What are the day-to-day challenges in the job?

CR: Because people know us as an emergency response organisation, our change of direction to apply our skills across a range of work from anticipatory action, preparedness to post-disaster recovery and not just emergency disaster response has to be managed. We want to be seen as globally diverse data and geospatial specialists. That concerns the way donors perceive us as well: to secure funding for new areas that we're moving into, we need to network.

I've just been to the UN Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management, for instance, where I met stakeholders, talked about where we're going and asked what they would like to see us do. We have to ensure we have the right staff and capabilities. As a global organisation, how can we hire people outside the UK and the EU so we can have a geospatial specialist in Indonesia or a data scientist in Colombia, for instance?

The operations side is another challenge – we need to think through the intricacies of labour law, and work out how, without having a legal presence in a given country, we could contract employees from outside the UK and EU. Are there any multinational companies with experience in international contracting that could provide some pro bono support and advice?

We want to be open to partnership opportunities that may arise so we can tap into professional help. For instance, a staff health department could provide pre-deployment support and advice for our volunteers, or an HR team could do a confidential post-deployment debrief where people can discuss what they have seen and experienced during a deployment or to just have a safe space to talk about the difficulties of working in a disaster zone.

LJ: How could Land Journal readers support your work?

CR: Climate change means the number and severity of disasters is on the rise. For a small agency such as MapAction, this increases demands on us to help countries prepare for and respond to crises. We don't currently have the funds we need to meet that need, neither do we have big reserves to draw on.

Please get in touch with MapAction's head of philanthropic partnerships, Zohab Musa, if you or your company can support us to use mapping and spatial analysis to help people in crises.