Dutyholders can be grouped according to those who have no obligations under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974, such as homeowners, and those who have a legal duty to comply, for instance highway authorities and commercial entities.

Establishing what the courts are likely to expect in each of these scenarios can be described in terms of the occupancy of the location, i.e. how many people or things could be harmed, the type of check, the credentials of the inspector, and the frequency of revisiting.

Dutyholders with trees and no business interest at their properties have no obligations under the 1974 Act – but they do still have a duty of care under civil law to take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions that cause a reasonably foreseeable risk of harm.

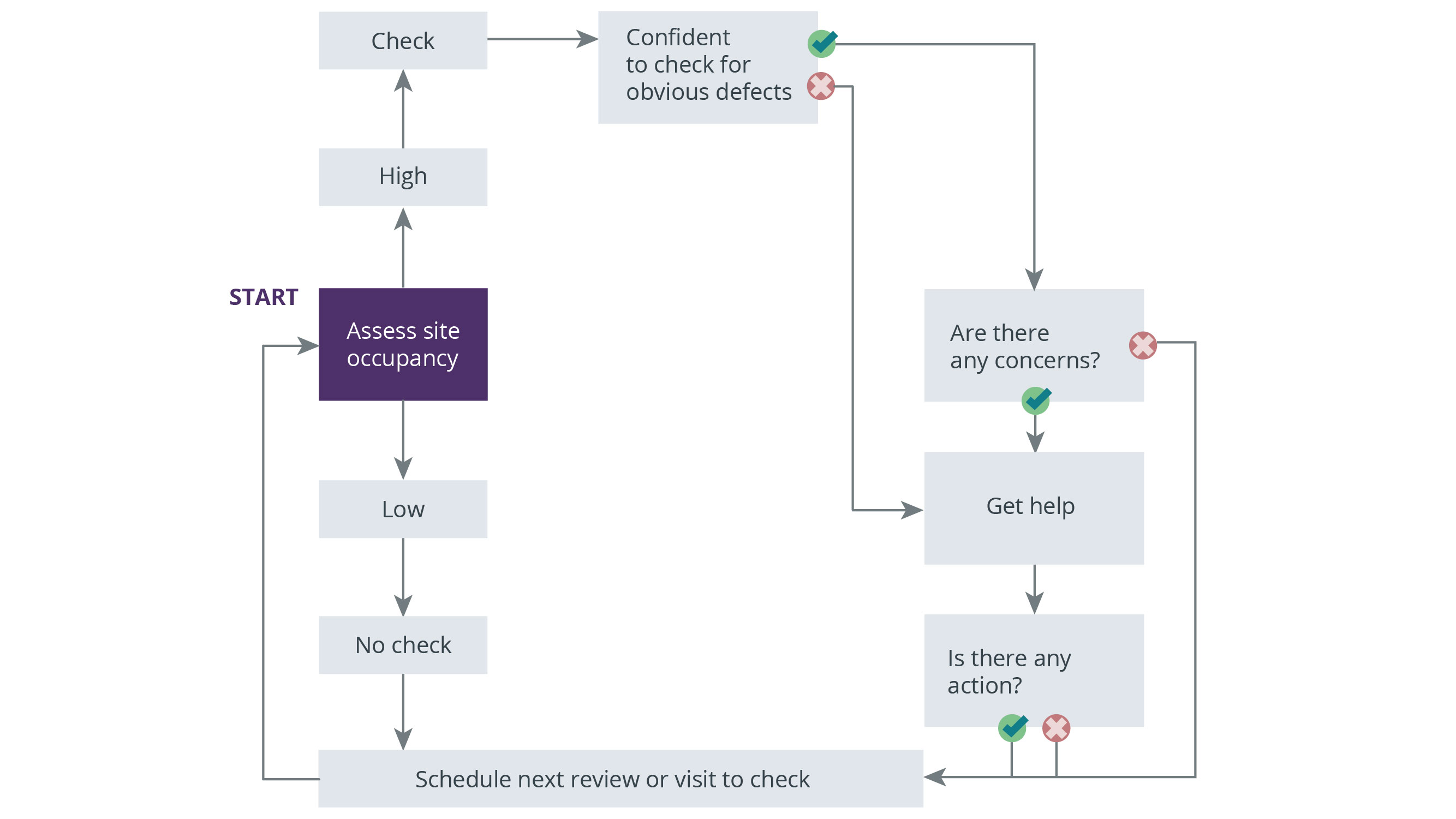

In practical terms, that means trees must be checked for obvious defects that could cause harm. Figure 1 illustrates a decision-making framework for dutyholders with no responsibilities to manage tree risk under the 1974 Act.

The starting point is to assess site occupancy, which provides a reliable indication of whether people or property could be harmed if a tree fails. The assessment of the level of occupancy needed to trigger a check is a matter of judgement for each dutyholder. If the occupancy is at the lower end of the range then no check is needed, and a future review must be scheduled. If the occupancy is at the higher end, the tree must be checked.

If dutyholders are not confident that they know what obvious defects are and can identify them, they should get help from a professional, such as a tree contractor or consultant, and act on that advice. If they are confident in their abilities, they can check their own trees.

If they see nothing of concern, then no immediate action is needed. If they discover a concern, they should get help from a professional, and act on it. The risk from all trees should be regularly reviewed, irrespective of whether it is the dutyholder or a professional who makes the check.

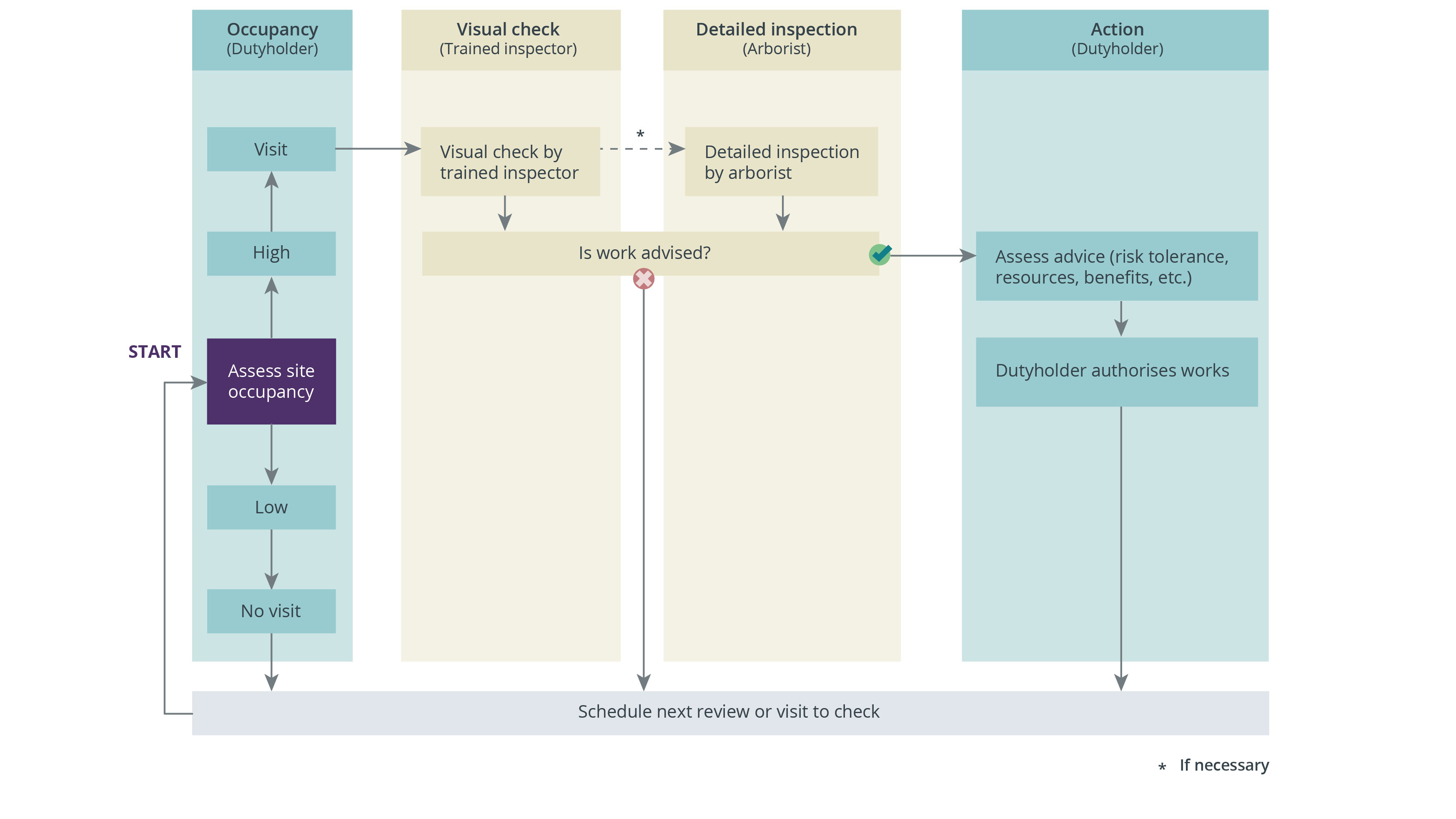

Dutyholders with business interests at their properties who have obligations under the 1974 Act also have a responsibility to take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions that would cause a reasonably foreseeable risk of harm. In practical terms, the process of assessing the risk and reacting to the findings can be shared between the dutyholder and the tree inspector, as shown in Figure 2.

Dutyholders usually know how heavily the land is occupied, and there is no need for expertise in trees to assess whether to visit to check them.

The assessment of the level of occupancy needed to trigger a check is a matter of judgement for each dutyholder. If the occupancy is at the lower end of the range, it is unlikely to need any specialist input. All that is necessary is to schedule a future review.

If the occupancy is at the higher end then a check is needed, and there is an expectation that it will be carried out by someone with enough experience or training to discover significant defects. This could be a trained tree contractor or consultant, or a person from another profession with specific training to recognise such defects.

If the check reveals no cause for concern, no intervention is needed and the next check is scheduled. If the check raises concerns, the need for intervention is assessed and the dutyholder is notified. If there is an imperative to keep the tree, because it has a high ecological value for instance, and the inspector is not sure about the implications of any discovered problems, or the extent of intervention required, a more detailed inspection by a trained arborist can be advised.

This is a much more detailed investigation than the check, and will clarify what intervention, if any, is notified to the dutyholder. How dutyholders react to this advice is for them to decide, based on their circumstances.

Controlling costs

There is no obvious expectation from the HSE or the courts that managing tree risk should be an onerous or disproportionately expensive burden on dutyholders. Most significantly, it is only necessary to record the area checked, the date, and who performed the check.

There is no requirement to keep a detailed inventory of every single tree checked. It is enough that all trees that could reasonably and foreseeably cause harm are included in a checking regime, and that those requiring intervention are identified in a way that allows management recommendations to be implemented.

Professional tree risk assessment is a complex process that requires specific training and experience to provide balanced and proportionate management recommendations. It can be a false economy to use poorly trained and inexperienced inspectors: a lack of confidence can result in them erring on the side of caution, often specifying unnecessary and costly management works.

Similar caution must be applied to employing the same company to provide both advice and contracting services, because of the obvious conflict of interest. An effective way to keep overall costs down is to use properly qualified, trained, and independently vetted consultants, such as the Arboricultural Association Register of Consultants.

National Tree Safety Group (NTSG)

The NTSG, on which RICS is represented, is currently updating its core guidance document Common sense risk management of trees.

The NTSG, on which RICS is represented, is currently updating its core guidance document Common sense risk management of trees. This document provides guidance for inspecting and maintaining trees; guidance that is reasonable and proportionate to: the low risk from trees, the benefits of trees, and the health and safety obligations of those responsible for trees.

As a national guidance document produced by an authoritative and representative group, its content and recommendations, if followed, should assist tree owners involved in personal injury or compensation claims when presented to the court as supporting documentation.

This updated guidance is due to be published shortly and will be subject to wider consultation after which the feedback received will be considered. The additional existing NTSG publications, the summary homeowner and landowner booklets, will also be updated in due course.

All documents will be available online from the website.

Jeremy Barrell is managing director of Barrell Tree Consultancy and an accomplished expert witness

Contact Jeremy: Email | Twitter

A full version of this article appeared as 'The implications of recent English legal judgments, inquest verdicts, and ash dieback disease for the defensibility of tree risk management regimes' in Arboricultural Journal, © 2021 Jeremy Barrell, published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

Related competencies include: Management of the natural environment