Early last year people and politicians were talking about a right to roam and public access to the countryside, thanks to a decision on wild camping taken by landowners Alexander and Diana Darwall.

The Darwalls own not only the 1,600ha Blatchford estate in Dartmoor National Park, but also the 6,474ha Sutherland estate in Scotland. The Blatchford estate includes Stall Moor, an extensive area of unenclosed moorland. In 2022 they went to court, claiming there was no right under the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985, to wild camp on the moor without their permission, and in January 2023 the High Court decided they were right.

Their lawyer successfully challenged the historic interpretation of the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985 that there is a long-established precedent of wild camping on the Dartmoor National Park.

The 1985 Act states that 'the public shall have a right of access to the commons on foot and on horseback for the purpose of open air recreation'. The Darwalls' barrister argued that 'the whole point of erecting a tent was to escape from the open air' and, 'if a tent is acceptable, then why not a wooden hut?' He claimed that any form of camping was not included in the definition of 'open-air recreation'.

The Darwalls use Stall Moor for pheasant shoots, deer stalking and holiday rentals and complained that camping there was a 'real problem'. It was therefore only 'reasonable' to receive compensation for the loss of control over who could camp on their land. The problems referred to were not detailed, however.

Following the removal of the right to wild camp in January, the Dartmoor National Park Authority took the dispute to the Court of Appeal, and in August won the restoration of the right for open-air recreation, which includes wild camping.

This was because the 1985 Act does not refer to the right to roam, but to 'open-air recreation'. It is worth clarifying that elsewhere in England, the right to roam does not include wild camping. Dartmoor is unique in this giving the right to 'open air recreation' rather than 'to roam'.

It is important because access to the more remote areas of the National Park is not possible in a single day, and without overnight stays these areas will become out of reach to those seeking to assert their right to ' roam' on these remoter areas, defined as access land in the Countryside and Rights of Way (CROW) Act 2000. So some Scots saw this case as an attack on the principle of the right to roam itself.

At the time of publication, the Darwalls' legal team has announced that it will appeal to the Supreme Court.

What is the right to roam in England?

In the CROW Act 2000, the right to roam is defined as the right for walkers to access mountains, moors, heaths and downs that are privately owned, and registered common land, defined as 'access land'. The 32nd report of the Commons Select Committee on Public Accounts of 2007 records that this amounts to 8% of the English landscape, 77% of which is in the north of England.

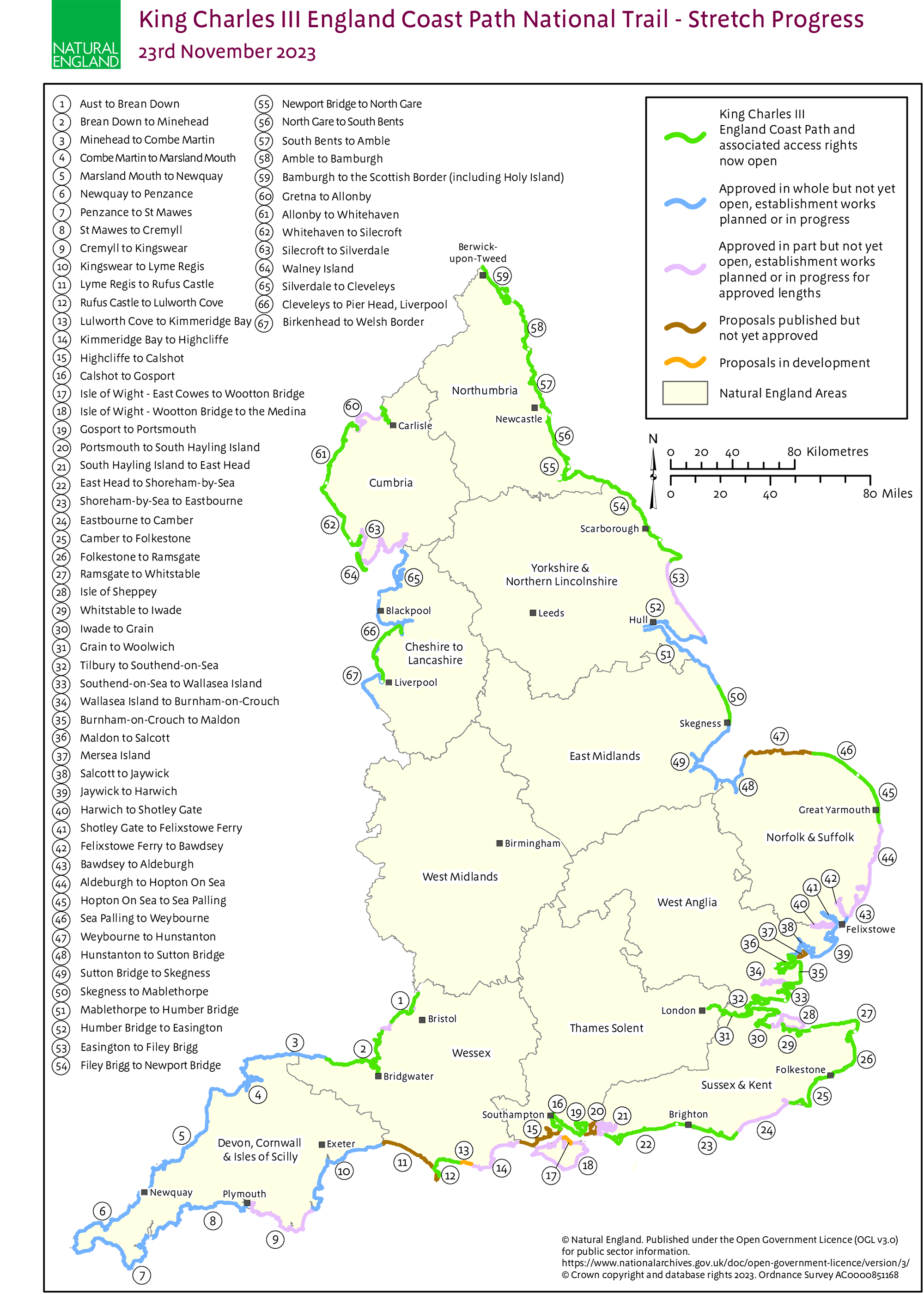

To this has been added the King Charles III England Coastal Path, which is planned to run the entire coastline of England. As of 2023 this has been negotiated, and around half the English coast is already open.

Map shows the stretches of the trail that are open to the public and those where work is still in progress. Right click to see the image in full view.

Legislation extends definition of trespass

The movement to improve access to the countryside for the public started in 1932 with the Kinder Scout mass trespass, but it was not until 2000 that the right to roam was granted for limited parts of England. In Scotland it was enabled in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, covering 30% of the national landscape.

According to the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000, access land can only be used for walking, running, watching wildlife and climbing, which clearly does not include wild camping. Access land must not be confused with rights of way, which have clearly defined permissible user groups and only allow users to travel along them and not linger or camp.

In 2021, after the first year of the pandemic and the increased recognition of the health benefits that nature offers, the government began a review of access to nature under Lord Agnew. However, in 2022 this was shelved and its findings will not be published. This follows the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022, which reclassifies some types of trespass as criminal rather than civil offences. Despite recognition of more need for access, legislation is restricting it further.

This has frustrated organisations pushing for greater access to the countryside such as the CPRE, Friends of the Earth, the Right to Roam campaign and groups such as walkers, climbers, kayakers and horse riders who have interpreted it as weakening their right to access the countryside.

The stated aim of the 2022 Act was to prevent unauthorised encampments; but its wording enables it to be used against anyone encroaching on someone else's property. Trespassers can now face imprisonment and a fine, depending on the location and nature of the trespass.

Landowners can remove access rights from access land for up to 28 days, at their discretion. Longer restrictions are also possible, by applying to the relevant authority, such as Natural England, the local National Park Authority or the Forestry Commission, depending on the location of the land in question, or the purposes of land management, public safety and fire prevention.

Land management includes any type of activity such as farming, forestry, sports or other events. There are several examples of such restrictions being granted for years at a time. For example, a shoot at Gurston Down in Wiltshire was able to restrict access from 2016 to 2021, on the grounds of disturbance to quarry during the pre-season and shooting season.

Alternative European models

Also in 2022, though, Green MP Caroline Lucas tabled a bill in the House of Commons to extend the right to roam in England to woods, rivers, green belt and more grassland, effectively increasing coverage to 30% of England.

She used the 2003 Act as her template. As described in the Scottish Outdoor Access Code 2005, this gives responsible access to most land and inland waters for the purpose of many listed outdoor activities, including wild camping.

Responsible access to roam exists in several other countries, including Austria, the Scandinavian nations, Switzerland, Estonia and Czechia as well as Scotland. Guy Shrubsole's 2020 Sunday Times bestseller Who owns England? notes that English landownership law grants the owner the right to exclude the public, whereas in these other countries the emphasis is different.

Central to all versions of the right to roam across Europe, is that:

- there are sensible, listed exceptions and modifications to this right; Scotland for instance excludes houses and gardens and land sown with crops.

- according to the Scottish Outdoor Access Code 2005, 'this right only comes with strict responsibilities to both the ecology and community of an area'; these responsibilities are expressions of the 'leave no trace' philosophy – no litter, no fires, no damage to trees, wildlife or other elements of the environment.

The argument made by landowners who do not support the right to roam is that they believe the public will cause significant damage to the environment, wildlife and crops. However, most people accessing the countryside do behave responsibly and are unconvinced by this argument.

Nimo Omer in the Guardian quotes Right to Roam campaigner Jon Moses: 'The impact that people have on their environment is pretty minimal when you compare it to industrial agriculture and other practices that are destroying the ecology of the countryside.'

However, even in Scotland there is dissatisfaction with the actual level of access. One particularly important case is that of the Drumlean Estate, which is in the jurisdiction of the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA). The estate is owned by entities in Liechtenstein, which were first reported to be obstructing public access in 2007.

Following consultations, there has been no improvement in access, despite the case being heard in the Sheriff Court in 2013, and repeatedly in the Sheriff Appeal Court from 2015 onwards. The argument used for denying access was for the 'protection of all animals, people and materials on the farm'. However this argument was consistently denied by the judges, and this case now sets a precedent in Scotland discouraging such an argument.

Overseas ownership of the estate means it remains closed to the public, and as of 2023 the LLTNPA has been unable to enforce the right to roam.

'Green MP Caroline Lucas tabled a bill to extend the right to roam in England, effectively increasing coverage to 30% of the nation'

Wild camping access is contentious

Following the relaxation of lockdown in 2020, there were many reported cases of irresponsible wild campers causing damage and behaving inappropriately. National Park rangers had to deal with campers and clear up the mess, and there was considerable frustration among locals. In 2021, wild campers were also blamed for a massive wildfire in Cannich in the Highlands.

However, even before the pandemic, LLTNPA held a public consultation on the subject in 2017 and introduced a camping permit scheme to relieve the pressure on some of the park's most heavily visited spots.

But concerned landowners need to be aware that the 2003 Act prohibits signs, notices, obstructions and the like that have no purpose other than restricting access rights. In addition, the act allows the local authority to serve a notice requiring obstructions to be removed, although there are numerous reported cases of such notices being put up in the national parks and not being removed.

The act further makes local authorities and national park authorities responsible for upholding access rights by asserting, protecting and keeping them open and free from obstruction. But it also lists 14 acts of the Scottish Parliament that curtail the behaviour of those using access land.

Weighing up wider right to roam

Following Lucas's bill and the recent defence of the right for the public to access the countryside in Dartmoor, the Labour party has pledged to extend the right to roam as it exists in Scotland to England.

Earlier cases mentioned suggest, however, that the law is not effective at forcing landowners in England or Scotland, in particular overseas owners, to observe the responsibility of granting access to land categorised as access land.

Half of Scotland is owned by 432 individuals, a few of these being overseas landowners including Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum and Anders Holch Povlsen as well as the Duke of Buccleuch, each of whom own vast estates.

The relevant English authorities also seem sympathetic to granting restrictions to landowners, and in Scotland are unable or unwilling to enforce court judgments forcing landowners to open their estates, as in the case of Drumlean.

It remains to be seen whether this thorny issue can be negotiated to the satisfaction of all concerned.

Gabriella Parkes is senior lecturer in Rural Economics and Event Management at Harper Adams University

Related competencies include: Access and rights over land, Land use and diversification