?$article-big-img-desktop$&qlt=85,1&op_sharpen=1)

Depending on the outcome of the Brexit negotiations, there are a number of possible policy directions for food and agriculture in the UK. Nevertheless, the central question remains whether the sector will be able to meet the challenges of competitive international trade, in or outside the EU.

- improving farming productivity – is it possible to intensify in a sustainable way?

- a new environmental land management system that ensures public goods for public money

- maximising trading opportunities, with increasing exports being a government priority.

| Average annual trend growth rate | |||

| 2000-07 | 2008-17 | 2000-17 | |

| Outputs | –0.1% | +1.3% | +0.7% |

| Inputs | –1.3% | +0.7% | +0.0% |

| TFP | +1.2% | +0.5% | +0.7% |

Table 1. UK agricultural TFP, 2000-17

| Average annual trend growth rate | |||

| 2000-07 | 2008-17 | 2000-17 | |

| Outputs | –0.1% | +1.3% | +0.7% |

| Inputs | –1.3% | +0.7% | +0.0% |

| TFP | +1.2% | +0.5% | +0.7% |

Source: Office for National Statistics; Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs

This period can be split roughly into two halves. Until the 2008 financial crash, aggregate output growth was stagnant, but with a decline in growth of inputs TFP consequently increased by an average of 1.2% a year. Since 2008, output growth has exceeded input growth, leading to a net trend growth rate of 0.5%.

Overall, TFP in agriculture since 2000 has grown at 0.7% a year. The annual trend growth in production and manufacturing as a whole was by comparison 0.3%, so in that respect the sector has performed better than the rest of the UK economy. However, from an international perspective all is not so rosy.

A major study by the economist Keith Fuglie, supported by the US Department of Agriculture, looked at TFP in more than 120 countries between 1961 and 2015. While the measurement methodology was slightly different to that of the Office for National Statistics, from whose numbers Table 1 is derived, Fuglie found the UK's annual growth rate was 1.1% – lower than most major agricultural exporting nations. Indeed, Brazil, China, France, India, the Netherlands, Thailand and Turkey had TFP trend growth rates two to three times higher than the UK, while those for the USA and Australia were also marginally higher.

Furthermore, the annual TFP growth of 0.7% for UK agriculture is above that of the subsectors using its products. Since 2000, TFP has averaged 0.6% annually for the food manufacturing sector, 0.3% for food retail and minus 0.2% for catering, with 0.4% being the average rate across these sectors. Given the increasing long-term dependence of agricultural prosperity on the efficiency of food processing and distribution sectors, this is worrying.

Trade balance

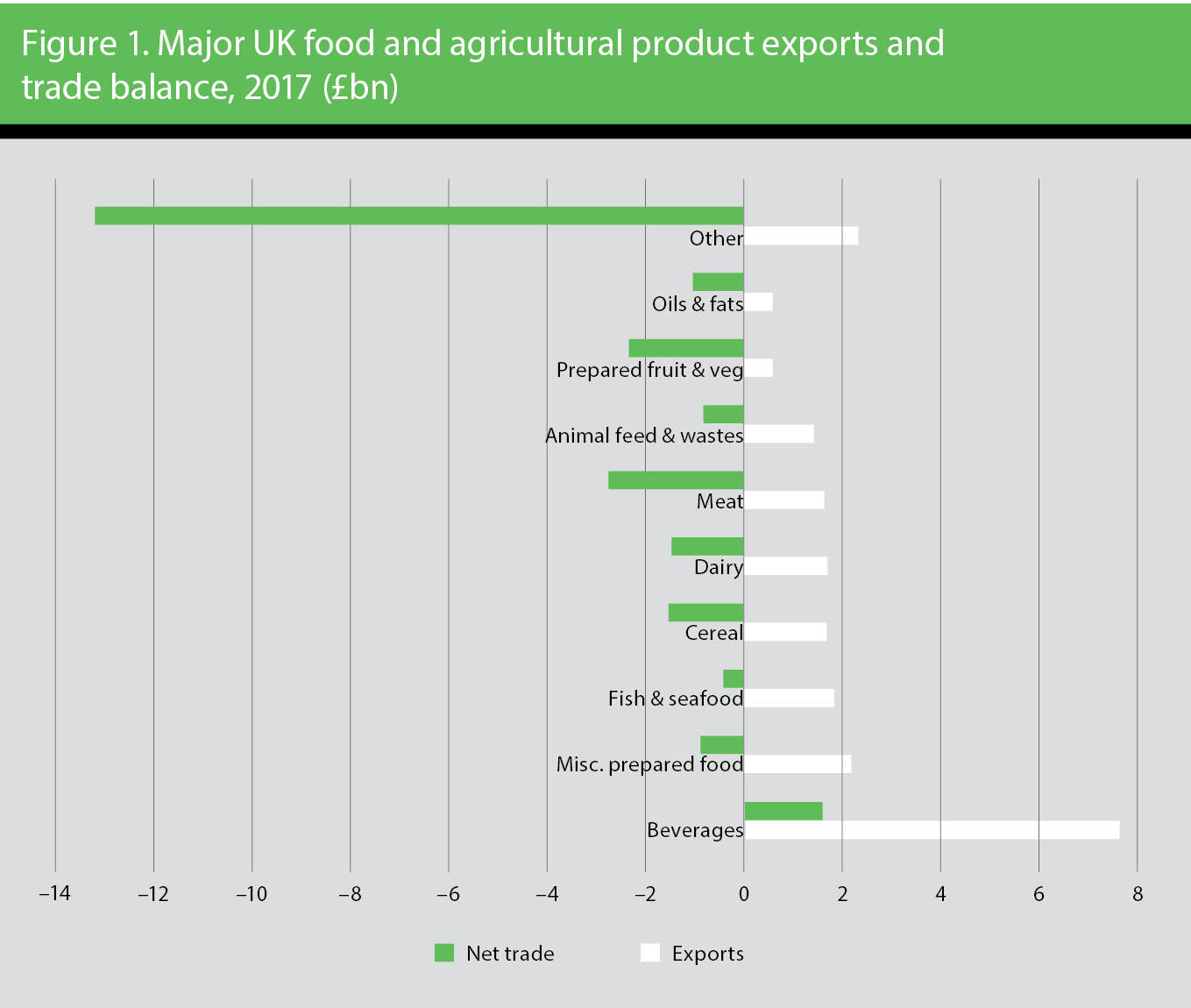

The UK exported more than £21.5bn of food and agricultural products in 2018. However, its net trade balance in the sector – exports minus imports – was still in deficit to the tune of £21.3bn.

- beverages, including spirits, earned a £1.6bn surplus on exports of £7.6bn

- processed cereal products had a £40m surplus from £400m of exports.

Even for major exports such as meat, dairy, miscellaneous prepared food and cereal, the values were generally less than half those of comparable imports. Of course these are large product group aggregates, and some individual products may do better than others. While all exports clearly contribute to reducing the trade deficit in food and agricultural products, it will still be a major challenge if future policy requires that an export-led sector significantly reduce the £44bn of UK food and agricultural products that are imported.

There are a number of ways economists measure comparative advantage and whether a sector of the economy is stronger than others in international trade. The two most common are the Balassa Index (BI) and the Lafay Index (LI). The BI measures a product's share of total exports from a country relative to the world trade share of that product in total world trade. Effectively it measures the relative degree of specialisation a country has in exporting that production onto world markets with BI>1 indicating specialisation.

The LI, by contrast, examines the relative importance of a country's net trade in a specific product/sector relative to the country's total net trade, thus including imports in evaluating its strength, with an index greater than zero signifying a product's comparative advantage in total domestic trade. Hence BI just considers comparative advantage and specialisation in exporting, and LI product or sector specialisation in total trade.

Based on 2016 data, beverages, milling products and miscellaneous prepared food were the only UK agricultural and food product groups that had both a comparative domestic advantage in trade and were export specialisations. Cereal preparations and dairy products qualified as export specialised product groups as well, although only just.

Looking at UK export specialisation in relation to similar product groups from other countries, however, the picture is not so positive. The UK's highest-placed group, beverages, does not rank in the top ten countries exporting these products – it is at 28 – while miscellaneous prepared foods, meats, cereal preparations, dairy products and cereals are ranked 34, 40, 52, 53 and 57 respectively in world trade.

So it is not only export specialisation that is important in gauging a country's pecific product strength in global markets, but the degree of specialisation compared with international competitors. On this count, the UK is at best a modest performer in some specific product areas.

Export potential

The potential for export growth, and indeed its prioritisation in UK agricultural policy, will depend on the trade arrangements with the 27 EU member states after Brexit, and how much further the domestic market is exposed to international competition than it has been as a member state itself. Production may also be constrained if UK policy seeks to de-intensify domestic agriculture; combined with global market conditions, all these factors will affect export opportunities.

What is clear is that, should the UK pursue an export-driven policy once it leaves the EU, it will find it difficult to redress the loss of trade with the bloc any time soon; currently, trade with the EU dominates UK agriculture and food exports and imports.

New Zealand is often cited as an example of how to make the transition from a supported agricultural sector with a single dominant market to a global exporter. Its food and agriculture sector was first prompted to diversify its markets by the UK's admission to what was then the Common Market in 1973 – the UK was until then its largest export market – and subsequently by the deregulation of subsidies to export sectors such as sheep meat and wool during the late 1980s.

The 1990s and early 2000s were a time of economic growth and trade liberalisation in South East and East Asia, markets on New Zealand's doorstep, and early trade deals with Australia, Singapore, Thailand, China and Malaysia from 1983 to 2009 were each concluded in no more than four years. But a deal with Hong Kong took nine years, and negotiations on the upgrade to the China free trade agreement are into a fourth year, with the Pacific Alliance into a sixth, and with Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan more than eight.

From a strategic perspective, the UK will need to make up for any lost trade with the EU in the event of a no-deal Brexit or ungenerous trade agreement with the bloc. Non-EU countries that have a relatively large share of the world's imports of a specific product will be important but difficult targets. Countries with smaller import shares but a growing proportion of the market could also present opportunities, but making the most of these will be a different matter. Winning a share of some larger markets with declining imports might still be beneficial.

Clear patterns have emerged for some major agriculture and food product groups in non-EU import markets over the past five years. For meat, dairy and cereals, it is mainly the 15 western EU members that have taken the largest shares of our exports, but their import growth rates have mostly declined and the UK has lost ground in many of them.

Outside the EU, there is growth potential in Hong Kong, China, the USA and the Philippines for meat, but opportunities for dairy and cereals are relatively fragmented. For cereal products, the UK has been losing market share in China, the USA and the Gulf states, countries that have been expanding their imports.

Beverages, the star performer of UK food and agriculture exports, have probably the most diversified market, especially outside the EU; however, they have been losing market share in import growth markets such as China, the USA, Hong Kong and Taipei, and also in those with declining import markets such as Singapore and Japan. The USA nevertheless dominates UK exports, taking 20% by value.

In conclusion, there are no easy trade deals to be struck with major economies or large countries. The shift to greater protectionism by the USA and its dispute with China have ensured that world trade has become less open, and the UK will face serious difficulties in terms of its future exports to the EU27, if in granting access to the US agri-food industries, it has to compromise on its current EU food hygiene, safety and welfare standards, that have been trailed as sacrosanct domestically after Brexit.

There is also a strong possibility that environmental pressures and policies may lead to reductions in UK agricultural output, although there may be policy-promoted productivity gains with lower output from even fewer inputs in both food production and processing.

Increasing public goods such as biodiversity, environment and landscape may not offer the greatest public benefit all the same if the economic output of food and agriculture as a whole diminishes, because public benefits depend as much on the numbers of people who can access them as they do on the provision of natural capital and ecosystem services. Balancing potentially conflicting policy objectives will therefore be a challenge, not least for a sector where most product groups have not distinguished themselves in terms of export performance and underlying determinants such as productivity, market diversification and innovation over a number of years.

Brian Revell is professor emeritus of agricultural and food economics at Harper Adams University

Contact Brian: Email

Related competencies include: Agriculture