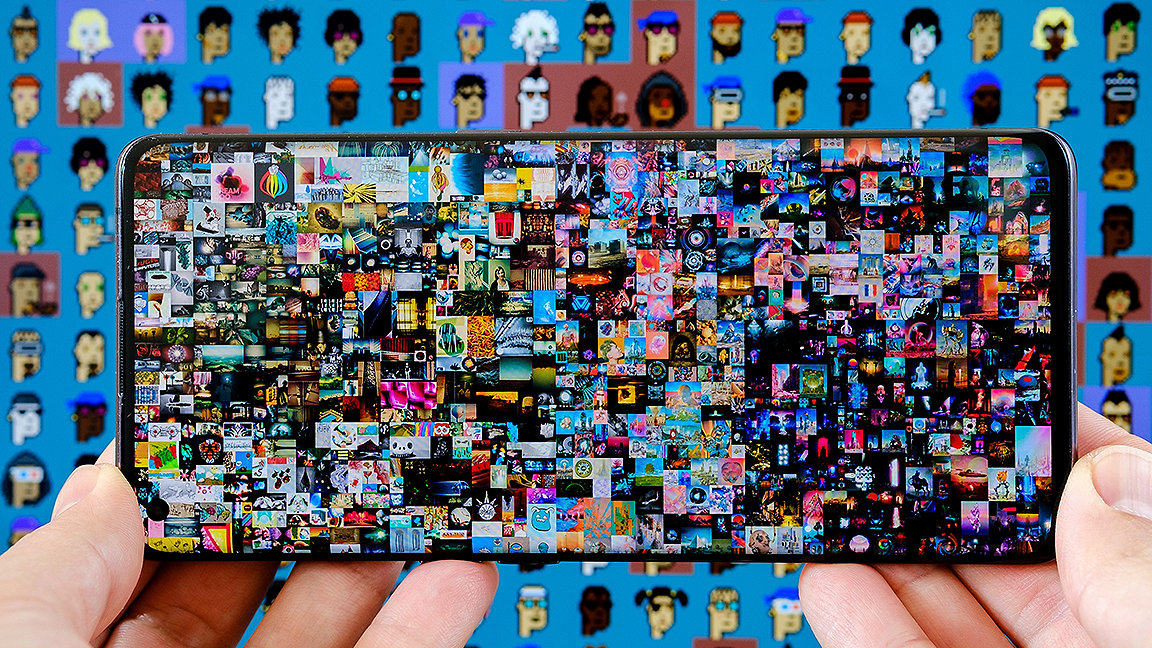

Christie's sale of Beeple's 'Everydays — The First 5000 Days' helped to establish NFTs as a medium for art

Historically slow to adapt, the art market is experiencing more online sales, blurred boundaries between galleries and auctions, a widening gap between the top and middle tiers of the market, and the pioneering frontier of crypto art.

Traditionally, the sector tended to be categorised into primary, secondary and wholesale markets. The primary market is where an item appears for the first time, such as at a gallery or directly for sale by the artist; the secondary market is where a previously owned piece appears for resale, such as at an auction house, another gallery, or by other forms of consignment; while the wholesale market is where a work is offered for sale to those who work in the trade, often at a significant discount.

Yet these traditional levels of the market may now be better termed spaces, as the means by which sellers and venues operate are increasingly overlapping. Economists are increasingly interested in where these transactions now occur, most notably in-person and digital transactions.

With the market experiencing so much transformation, sellers must adapt rapidly to stay viable, and often engage in multiple spaces simultaneously. This evolution affects the way that valuers analyse the market.

Lines between auctions and galleries blur

Unlike other assets, fine art's behaviour is not easily quantified. After all, its currency is not only monetary; it also confers prestige and has emotional associations. To own a work of art is to possess a powerful signifier of identity. This makes analysing the market a problematic endeavour.

There is an additional challenge in that access to private sales data is rarely given to those outside the art world. Exclusive networks within the trade rely heavily on word of mouth to compare values and sale prices, let alone comprehend the surrounding terms and conditions. When it comes to auction sales, even supposedly public records are not necessarily reported correctly or vetted by a reliable source. Neither are they obliged to disclose behind-the-scenes guarantees.

In general, the art world is minimally regulated by national and international law, with no uniform requirements for documenting transactions. The parties involved and arrangements made for a particular sale often remain unknown, allowing ample opportunity for manipulation and crime. Since determination of price varies by seller, object and negotiation, due diligence tends to be the responsibility of the buyer, many of whom choose to trust reputation rather than independent investigation.

Because high-end art continues to increase in value as a capital asset, some countries have proposed legislation to allow more oversight. However, these policy proposals rarely become law, because legislators view illicit art activity as negligible when compared to wrongdoings in other sectors.

This obscurity becomes murkier still due to the confluence of sales strategies by dealers and auctioneers: they nurture long-term relationships with collectors by becoming a one-stop shop for all their art needs, offering advisory services and enabling the transport of acquisitions.

In addition, gallerists and auction houses alike engage in public and private sales. Conventionally, galleries were the ones who dealt in private sales, while auction houses devoted themselves to public lots. Yet for decades now they have been venturing on to each other's terrain.

These days, auction houses are involved in all parts of the market, giving third-party guarantees, conducting private sales, providing advice, and offering works that are appearing for sale for the first time.

Meanwhile, galleries borrow from the auction playbook by creating a sense of urgency to buy at time-sensitive events. Art fairs and pop-ups add a theatrical element that buyers crave as part of their collecting experience. Websites also offer virtual booths for dealers and auctioneers. Platforms such as 1stDibs now have auction channels on their websites, allowing dealers to participate with fewer intermediaries.

Shifting network of relationships

Along with this hybridisation between auction and retail, consolidation is another trend. Many gallerists have joined forces, such as the consortium LGDR in New York. Auction houses are also partnering; UK-based Bonhams recently acquired Skinner in Boston, and Artnet and Chinese auction house Poly are working together to put on a special sale this summer.

Despite consolidations of former competitors, a small number of top-tier auctioneers and dealers continue to dominate the market. At auction, the big three remain Sotheby's, Christie's and Phillips. Galleries have also seen the rise of the mega dealer, whose business comprises several international outposts where they represent living artists as well as broker secondary sales. Larry Gagosian perfectly embodies the idea of the mega dealer.

The big three and their consolidated competition all aim to leverage international networks and place specialists strategically in cities with major art markets. But they know they need each other to exist, creating cooperative yet competitive relationships.

A recent demonstration of this was Gagosian's record-breaking bid at Christie's for Andy Warhol's Shot Sage Blue Marilyn for $195m. The price achieved made it the most expensive 20th-century artwork to sell at auction.

His winning bid was certainly a boon to Christie's, as the piece was the second most pricey artwork sold by the house. It also benefited Gagosian's status as the pre-eminent dealer in the world today, and there was significant press coverage of the purchase.

Blurring also happens in the form of crossovers with other markets – notably luxury goods, financial services, and blockchain technology. The financial sector has long wooed the art world and attempted to convert art into a more trackable asset that can be monitored as if it were a stock option. However, it may be the emerging market for crypto art – discussed below – that finally enables the desired commodification.

Meanwhile, living artists have with the help of gallery representation collaborated with luxury goods manufacturers to attract buyers' attention. Louis Vuitton has set the trend for merging high-end fashion with blue-chip art, offering exclusive handbags designed by artists such as Yayoi Kusama and Jeff Koons.

Contemporary and crypto art focus interest

While cultural differences may affect purchases made by high-net-worth (HNW) individuals, they seem to agree on collecting a specific roll-call of contemporary artists.

The simplest reason for this is supply. Unlike the previously top-performing category of works by modern and impressionist artists, which are necessarily limited in number, contemporary art is abundant. With more buyers willing to spend significant money, a wider net must be cast. Sellers enjoy contemporary works because they can choose from a plethora of artists to promote and showcase simultaneously at auctions and galleries, therefore raising resale prices rapidly.

However, the intense promotion of a specific subset of contemporary artists, sometimes referred to as blue chip, has caused several problems. It can negatively affect living artists whose auction values exceed their gallery prices: their status can skyrocket from mid-career only to plummet within a few years when they are no longer a hot commodity.

It also reflects that the wealth spent in the upper tier of the art market is at the expense of a squeezed middle. Most of what might be considered historical art, created before 1900, tends to languish in comparison to astronomical prices commanded by their contemporary counterparts. The growing number of ultra-HNW individuals with a homogenous collecting style and the sudden arrival of crypto art exacerbate this polarisation.

Crypto art, best recognised in the form of non-fungible tokens (NFTs), is changing the rules. The watershed moment was the Christie's sale of Everydays — The First 5000 Days by Beeple, which ushered in NFTs as a type of art media that won't be ignored. The sale of this work at auction helped legitimise NFTs in the art market; it also attracted a new set of potential buyers who are more closely associated with cryptocurrency and comfortable with speculative buying.

While the NFT category is more volatile and will take time to settle, it has prompted the art market to consider seriously what is on the horizon. Who will be the leaders of crypto art platforms? Will those more used to the traditional market make the leap? The champions will likely become digital ambassadors to the art world. In the meantime, top-tier auction houses and mega dealers contend to become titans in NFT sales.

'The wealth spent in the upper tier of the art market is at the expense of a squeezed middle'

How changes affect art valuations

It's no longer enough to describe a sale as taking place at retail or auction. Did the artwork list for different asking prices, according to the venue? Did an auctioned lot meet the hammer price due to a private guarantee? Context is critical when reviewing comparable sales.

In addition to being connoisseurs, professionals must stay abreast of technology – both as a medium for art and as a mode of selling it. To do so, they can read reputable, market-specific news outlets, especially on topics of technology, finance and crypto art. They can also become involved in communities that discuss new media art, whether it be a LinkedIn group or a Clubhouse chatroom, or attend presentations by those involved in art-tech ventures.

The valuer's job is made tougher by the speed of change, combined with a lack of access to verifiable data. Transparency and regulation lag behind the shift from market levels to spaces, despite the increased financialisation of fine art. With reliable records scarce in an already tight-lipped community, discovering the factual circumstances behind sales is a difficulty that appraisers face daily.

The best strategy is to communicate specific findings and challenges encountered. The more explanation that is provided about the dynamics of a particular fine art category, the more resilient the valuation analysis will be.

Courtney Ahlstrom Christy is an art valuer and principal of Ahlstrom Appraisals LLC

Contact Courtney: Email