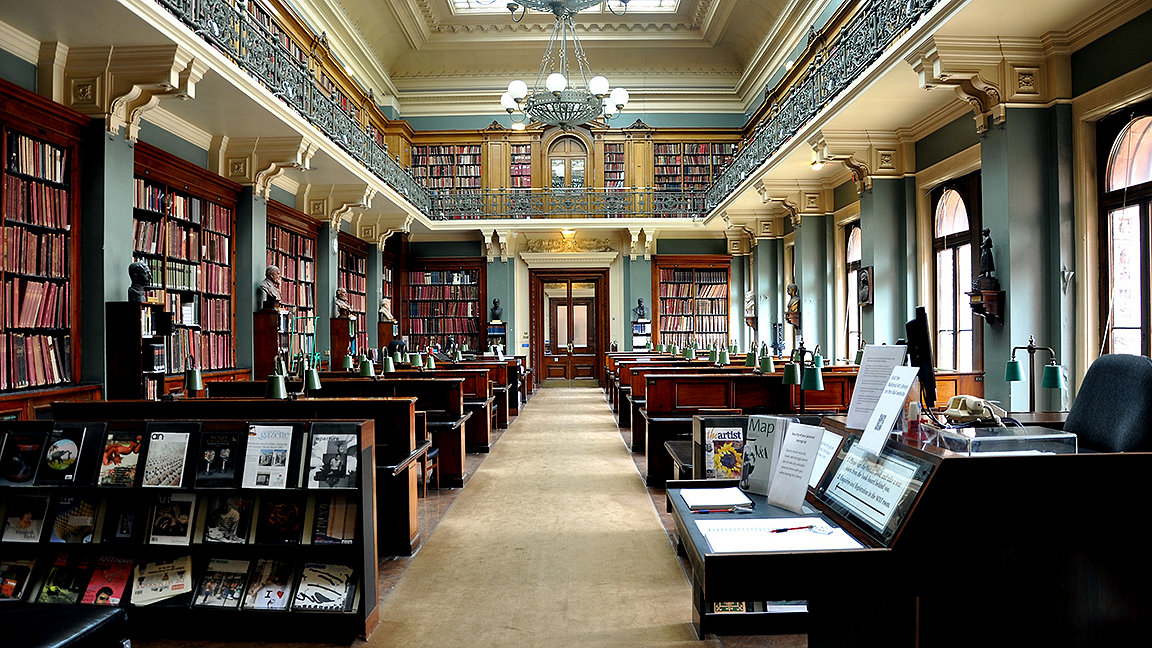

Andreas Praefcke, National Art Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 19 June 2011 © WikiCommons

It often seems that provenance is just a bulleted list of dead people that appears as a formality when completing art transactions. However, the list is only one piece of the provenance puzzle.

A comprehensive understanding of an artwork's ownership history can shed light on clean title, authenticity, condition issues, opinions of value, and even current art-historical interpretations. Without such information, an artwork may not be considered saleable by the relevant marketplace.

Clean title, aka valid title

"Indisputable right to ownership of property, supported by full provenance of the item since discovery or production."

International Council of Museums (ICOM): Code of Ethics for Museums

With services such as fine art title insurance, art fair vetting committees and commercial databases at our disposal, many of us do not pause to contemplate the implications of buying an artwork with little to no provenance. Yet these services are not catch-alls; rather, they are due diligence tools that can contribute to your provenance research efforts. As such, this article endeavours to shed light on some of the most common questions valuation specialists may face when reviewing the provenance records of an artwork or collection.

How to identify gaps in ownership

One of the most common questions people ask me about provenance is: ‘How do I recognise a gap in ownership?' These can often be identified quickly. When reviewing a bulleted list of past owners, each line entry should contain as much information as possible – the owner's name, location, dates of ownership, etc.

If there is no dated information or supporting documentation to indicate how the artwork transferred from one owner to the next, you have identified a gap. For example, let's take a quick look at the sample provenance related to a c. 1872–73 Corot painting sourced from a 1994 auction catalogue record:

-

M. O'Dard

-

M. Lagarde

-

William Astor, Esq., New York

-

Richard Green Gallery, London

Here, there are no dates indicating the duration of ownership for any of the listed parties. As such, a researcher looking at the 1994 auction record is faced with a gap of around 122 years.

This example leads directly to the second most common question I face: 'When should I do more research into a gap in ownership?' The answer: always.

Some of the most commonly recognised gaps to be wary of are those related to the Second World War and discriminatory practices of the Nazi era (1933–45). However, gaps can also arise from various other situations. For example, a gap may reflect that someone did not have the right to sell a work. A few examples include:

-

artworks that are part of unsettled divorce proceedings or other litigation

-

loans against an artwork

-

group ownership of an artwork, where an individual party claims sole ownership or seeks to sell without permission from the rest of the group.

Each of these situations can be hidden in the gaps, and each can have negative connotations for acquisitions, sales, loans and/or valuations.

'A gap may reflect that someone did not have the right to sell a work'

What is verifiable documentation?

One of the key components to deciphering the validity of provenance records is to have a strong grasp of what qualifies as verifiable documentation. So, what exactly is verifiable documentation, and how do you know if you have it?

Verifiable documentation is documentation that proves or corroborates the bulleted list of previous owners, exhibitions orand literature entries tied to a specific artwork. In other words, it is documentation that specifically references the artwork or collection being researched – examples include original bills of sale and archival records. Notably, the definition excludes provenance entries such as 'Private Collection' or 'Private Dealer' that are not corroborated by supporting documentation. Such entries should not be considered a reliable or verifiable record of the transfer of clean title or authenticity.

Distinguishing historical research from provenance research

When looking to locate or assess verifiable documentation, researchers must also distinguish between the methodologies of historical research and provenance research.

Historical research can, by definition, be quite unbounded, as researchers endeavour to learn about a particular subject, person or question. They may scour archives and libraries looking for an answer. However, even if researchers do not find the specific answer they were seeking, analysis can often be crafted out of their findings, or lack thereof.

At the same time, the scope of fine art provenance research is singular. Researchers are looking for concrete results: verifiable documentation that references the artwork or collection being researched. Without this, the scope of work cannot be met, and accurate assessments of the artwork's clean title, authenticity or ownership history cannot be made. While historical research may greatly bolster your understanding of the period for which you are conducting provenance research, it is the verifiable documentation that will help trace the artwork(s) in question.

Evaluating certificates of authenticity and appraisal reports

As part of the research process, some of the most common paperwork you will encounter comes in the form of certificates of authenticity (CoAs) and appraisal reports. But how do these documents contribute to your understanding of an artwork's provenance?

Proof of authenticity is vital to accurate valuations and an artwork's life on the market. As such, CoAs are often issued in conjunction with an artwork to establish that the piece in question matches sales-floor advertisements. These documents often list the artwork's identifying specifications, such as artist, title, medium and dimensions, and an assertion of authenticity.

However, CoAs rarely, if ever, touch on clean title or ownership histories. For example, the antiquities market is rife with pieces that are sold with guarantees of authenticity but lack the appropriate documentation to support clean titles. As such, researchers should verify what documentation the source countries require for items to be exported and sold legally. In many cases, a CoA will not be enough to prevent an item's seizure and the owner's subsequent loss of investment. This assertion applies to objets d’art of all mediums, eras and price points.

At the same time, appraisal reports can be informative starting points for provenance research. However, when assessing the validity of the ownership information included therein, it is important to note that most valuation reports that comply with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) and RICS Valuation – Global Standards (Red Book Global Standards) will often indicate that the appraiser is not an authenticator. Furthermore, these reports often indicate that the valuation specialist will not comment on 'authenticity, attribution, clean title, provenance, etc.' unless there is a specific reason for them to do so in assigning an opinion of value.

From this perspective, the provenance information included in such appraisal reports should not be taken at face value. For provided provenance information to be deemed credible, it should be accompanied by verifiable primary-source documentation that traces an artwork from its point of creation to the present day. This rule should encompass any secondary source listing provenance information such as written reports, auction catalogues, or catalogues raisonné.

RICS podcast: Applying art valuation principles in America vs Britain

What is the value of art? The varied interpretations of value in art makes the discipline a difficult one within which to offer valuations.

This RICS podcast looks at how to apply frameworks in a market with increasing complexity due to the advent of NFTs, wealthy outsiders influencing the market, and the challenge of provenance research. Listen to Jonathan Fothergill in discussion with Tom Flynn and Alvah T. Beander here.

Moving forward with provenance

The goal of all provenance research and due diligence efforts is to locate verifiable documentation that confirms, revises or expands the bulleted list of past owners. As such, art market professionals, including valuation specialists, should thoroughly assess the provenance of each work they encounter. What does the market require for a specific artwork or artist's oeuvre in relation to questions of authenticity, levels of available documentation and gaps in ownership? These can be difficult questions to answer for many works, and specialists should seek expert assistance where necessary.

Accepting unverified provenance information at face value can have wide-ranging impacts, including a loss of investment or saleability. For example, if an artwork does not meet market requirements for saleability, valuation specialists should adjust their opinion of value to reflect the appropriate marketplace. Opinions of value do not stop with an appraisal report – they can influence insurance premiums, estate taxes, or even transactions. And it is the comprehensive review of provenance that will effectively enable valuation specialists to assess questions of clean title and authenticity when assigning opinions of value.