Illustration: James Andrews

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted a wholesale re-evaluation of the buildings in which we live and work. Offices have emptied out, people have found their homes unsatisfactory for spending extended amounts of time in, and many have caught the virus – or lost loved ones to it – because of poor air quality in the spaces we inhabit. It’s clear that we need to change the way we build to safeguard our health and improve our wellbeing.

“This pandemic is a pandemic of buildings,” says Orla Hegarty, assistant professor at the School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Policy at University College Dublin, and an adviser to the Irish government’s pandemic response team. “If we all lived in outdoor air quality there would be no pandemic. We have adopted building standards that are adequate for oxygen but not for disease protection, and we haven’t kept public health standards and ventilation in step with technological changes and energy efficiency requirements.”

There is increasing scientific consensus COVID-19 is mostly spread by shared air, rather than surfaces. It’s largely transmitted indoors and particularly in poorly ventilated spaces. It’s therefore likely to reverse the decades-long movement to seal buildings and prioritise insulation over ventilation. The focus will be on having openable windows where possible, and as many fresh influxes of outdoor air through mechanical ventilation where not.

More fresh air would not only reduce the risk of disease transmission, but would also improve wellbeing and cognition, spur efforts to reduce outdoor air pollution, and, if done right, cut energy consumption. The pandemic is expected to accelerate trends that have been around for a while, such as openable windows, outdoor spaces, more passive heating and cooling, and improved ventilation.

“Everything is aligning – the wellness agenda, sustainability, carbon emissions, stopping infection spread – and a lot of that is around how buildings use air,” says John Bushell, a principal architect at KPF. Bushell notes that London planning regulations require new builds to reduce carbon emissions by 35% against a 2013 baseline, while aligning with the Paris Agreement means cutting emissions by at least 70%. “We know the only way of doing that is involving natural ventilation in buildings.”

The most obvious way to do this, of course, is opening a window. The downside to this, of course, is that doing so while having the heating on would reverse energy savings. In buildings with mechanical ventilation, opening a window can cause complications, so more outdoor air could be driven through the heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system instead.

To reduce active heating and utility bills, one solution is mechanical heat recovery ventilation, where heat is transferred from the air being expelled from the building, to the outdoor air being brought into the building. Finally, “night time cooling”, or opening windows or vents overnight, could passively chill and refresh air in buildings only used during the day.

Although every building and room is different, around five to six air changes per hour are recommended to prevent transmission of COVID virus particles. A single air change can reduce contaminants by up to 63%.

Of course, one impediment to adding more outdoor air is pollution. This is why it's imperative to tackle both the immediate threat from COVID-19 as well as accelerate the energy transition. In Paris, local authorities have capitalised on empty streets during lockdown to pedestrianise and add cycle lanes at an unprecedented rate. But where pollution persists, and where noise pollution prevents windows from being opened in lower storeys, there are some other ways to take in cleaner air.

KPF's design for Hong Kong University of Science and Technology's Guangzhou campus, currently under construction, "will incorporate a combination of active and passive thermal comfort strategies to guarantee the wellbeing and enjoyment of occupants".

“If you’re worried about outdoor air quality, you take it in from higher up in the building,” says Bushell. KPF are implementing strategies to use “atrium air shafts” to allow natural ventilation in deeper floor spaces. “Then it’s about how much airflow we can get to happen naturally, assisted by a very-low-duty fan if needed.”

Filters are also vital for blocking out pollutants and pathogens. To combat COVID, HVAC systems in many buildings will need to upgrade to high-efficiency filters – ideally HEPA – which would remove a great deal of virus particles. Systems also need to be calibrated for 40-60% humidity to reduce transmission of pathogens, which are more easily spread in dry air. And it’s more important than ever that spaces are partitioned according to their ventilation system. Tenants often erect walls for corner offices and conference rooms that disregard the location of air ducts and vents, leading air to stagnate behind closed doors.

“There should be regulations that say you have to adjust the mechanical, electrical and plumbing design when you redesign an office space and cellularise it,” says Steve Morris, programme lead in property at RICS. “Some people say open-plan spaces are causing contamination. But actually, it allows you to ventilate better. And less cellurisation allows cleaning regimes to be conducted and monitored better, because there’s no locked doors.”

Many buildings with HVAC systems currently re-circulate around 80% of their air, according to Kevin Van Den Wymelenberg, a specialist in indoor air and head of the Institute for Health in the Built Environment at the University of Oregon.

“Most buildings have excess heating and cooling capacity,” he says. “That means you can probably drive more outside air and still maintain comfort.” But he warns that this may create condensation, and might necessitate more frequent filter maintenance, because outside air contains more particulates.

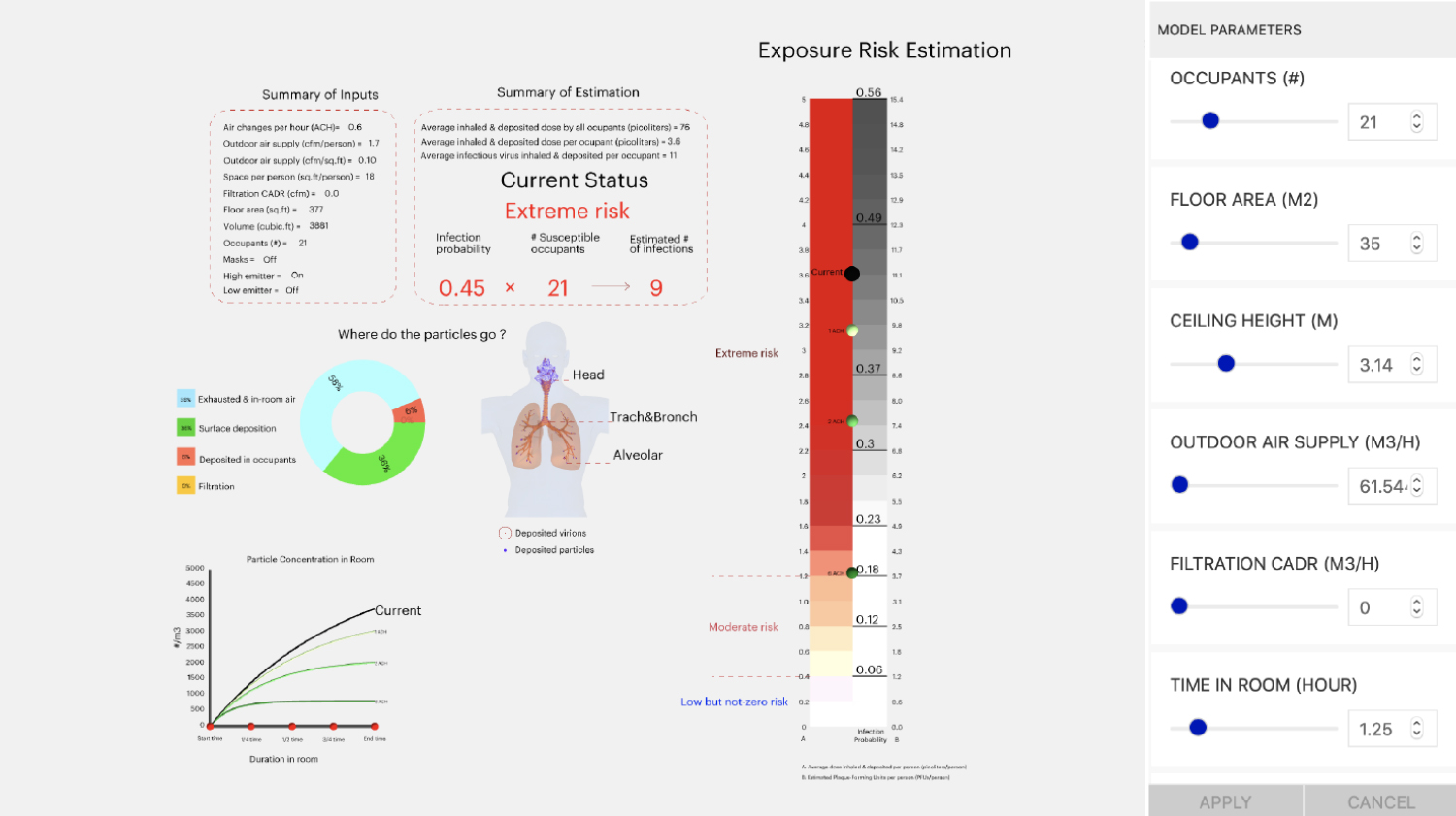

Van Den Wymelenberg and his colleagues have built a calculator to estimate exposure risk to COVID-19 indoors. By toggling variables such as the number of occupants, the size of the room, ceiling height, outdoor air supply and filtration capacity (CADR), the Safe Air Spaces Estimator calculates the probability of infection if someone with COVID-19 is in a space. In the future, such calculators may be used to judge when to pump more outdoor air in, or to increase filtration efficiency. They may also reassure occupants that the space they are in is safe.

Van Den Wymelenberg and his colleagues' calculator to estimate exposure risk to COVID-19 indoors

Carbon dioxide monitors, which are inexpensive and readily available, could also be used to measure air circulation. A reading of over 1,000ppm means exhaled breath is building up in a space, and if someone has a respiratory infection, others could be more readily infected.

However, both of these methods only measure the potential of transmission if an infected person is present, and do not count for how closely people are standing to each other. The ideal would be a sensor that can detect viruses. Enviral Tech, a company for which Van Den Wymelenberg is an adviser, provides kits to detect the SARS-COV-2 virus particles on surfaces and in air filters. They are currently surveilling more than 100 care homes in the US, with a 24-hour turnaround on results.

“I’m dreaming of a future where there’s a real-time viral detector in your building. With that data you can choose how to operate the building,” says Van Den Wymelenberg.

In the meantime, he recommends certain structural changes to lower transmission risk: higher ceilings, for example, increase air flow. Large windows let in more light and therefore more UV-C, the wavelength at which ultraviolet light kills bacteria and viruses. Along the same lines, traditional antibacterial materials such as copper and untreated wood may see a comeback, while we will can expect to see an increase in sensors and automation in touch points such as buttons and door handles.

There has also been much concern about lifts being hotspots of transmission. Reducing capacity so that people can socially distance is not going to be sufficient, since aerosols can stay suspended in the air for hours. An extraction and ventilation system on top of a lift, with a filter, is therefore preferable, according to Hegarty and Bushell.

And what about the occupants themselves? In a post-pandemic world, how comfortable are we all going to be about sharing the same spaces? Such a mood shift could lead to buildings with more space per occupant becoming prized.

“I do think dramatic densification is over, I think some people who went for that are regretting it,” says Maureen Ehrenberg FRICS, CEO of Blue Skyre IBE and former global head of real estate strategy at WeWork. “It’s not just about space productivity, it’s about: ‘How do my employees do their best work?’”

“I’m dreaming of a future where there’s a real-time viral detector in your building” Kevin Van Den Wymelenberg, University of Oregon

The same goes for increased costs from HVAC upgrades, or increased utility costs, says Ehrenberg. “It’s totally worth it, because people are healthier and safer. And there’s more oxygen in the air which means their cognitive power goes up, so they’re more alert and productive.”

As many people have found it possible or even preferable to work from home, luring people back to the office will mean assuring them that the building is not only safe, but an invigorating place to work, says Ehrenberg. Indeed, tenants are on the lookout for spaces with openable windows and high air quality, according to Bushell.

“Let’s say the previous model was that you wanted to maximise the size of the building, and minimise the space that each person uses. That’s all completely wrong. The buildings that are more generously planned out are the ones people can imagine using much more,” he says. “In office terms it's a matter of survival. They're the places tenants want to move into. The tenants are not looking at efficiency of space, they’re measuring by ESG [environmental, social and corporate governance] and CSR [corporate social responsibility].”

Of course, more space per occupant, more outdoor spaces, better ventilation and filtering of air will all cost money. However, some of these may be cheaper than labour-intensive frequent disinfection of spaces, which now seems to be less important than air quality. And higher costs may be unavoidable if tenants would otherwise shun the building. Investments might also be forced by new regulations as governments begin to process the science around airborne transmission of viruses. We could even see the introduction of new metrics, such as measures of the humane quality of a space, or an “optimum” amount of space per person rather than a minimum or maximum.

The silver lining of the pandemic will hopefully be a push back on some of the unhealthier trends that have emerged over the past few decades – insulation at the cost of ventilation, densification, cramped dimensions – as the arc of progress shifts to optimising human health. In some ways, it’s a return to the past, when “fresh air” was a healthcare mantra.

“All the principles of architecture have a strong public health background,” says Hegarty. “Daylight, sunlight, fresh air, openable windows, high ceilings, balconies, shelter, spacious rooms. They’re healthier buildings. Light and air, a view and mental health, space and privacy: many of these are the things people have tried to engineer out for property investment.”

“The previous model was that you wanted to maximise the size of the building, and minimise the space that each person uses. That’s completely wrong” John Bushell, KPF