In an east London carpark, part of a rundown area ripe for redevelopment, a temporary arena has become a site of pilgrimage for thousands of global music fans. They are flocking to watch the visually-resplendent, virtual reunion show of Sweden’s greatest musical exports, ABBA.

Opened in May 2022, the 3000-capacity ABBA Arena at Pudding Mill Lane, near Stratford in London, is home to ABBA Voyage, a holographic depiction of the group in its 1970s heyday. The life-size “Abbatars”, are projected on to a 65-million-pixel screen to perform alongside a live band and backing singers, creating a cutting-edge digital show. It’s all part of the growing immersive reality sector, a slice of the entertainment market that was worth $61.8bn in 2020 – up 19% in just one year.

But, for all the technological innovation of the performance, the arena too sets a precedent: designed by entertainment architects, Stufish, and built by ES Global, it is the world’s largest demountable venue. Its unusual hexagonal shape has been specifically developed to give uninterrupted views of the immersive concert. Building an arena specifically for the ABBA Voyage experience may seem profligate but at the end of what is likely to be a five-year residency, the sustainable, flatpack venue can easily be moved. It will be packed up and transported to the next location, making way for planned development on site.

The concert itself and the venue have been instant successes so could this change the way musicians decide to perform, demanding their own custom-built, transportable arenas that are completely adapted to their needs?

“It’s definitely upped the game, and it will be interesting to see how others react,” says Alicia Tkacz of Stufish, a lead architect for the ABBA Arena. The studio was established in the 1970s by Mark Fisher, who worked with Pink Floyd and the Rolling Stones, and the practice more recently designed Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way Ball” world tour, and Beyonce’s 2018 Coachella performance.

There are few groups out there with ABBA’s power to pull in concert-goers night after night – nor do many have the ABBA-sized wallet to mount such a show. The Stratford model, however, is an example of what can be achieved – essentially, an extremely high-tech version of the travelling circus rolling into town.

“The [ABBA arena] is about that next stepping stone, where other people can think, ‘I can do that’. OK, maybe not on the same scale… but with demountable, you can do anything really, it’s just a case of time and money,” says Tkacz. “The bigger the structure, the longer it’ll take to [dismantle] and move, and the more expensive it is.”

Stufish has been exploring the idea of demountable venues for years, but the ABBA project “allowed us to realise and do it for the first time,” says Tkacz, adding, “Other demountable venues exist, but not on an arena scale. [ABBA] is taking it up to that scale, [knowing] how you take it all down, fit everything into a truck or a container to move: that needs to be factored in at the beginning of the design process.”

The Stratford site was chosen by the ABBA group members themselves, because of what the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC) has achieved with its east London site. The LLDC was formed in 2012 with a mission statement to “use the opportunity of the London 2012 Games and the creation of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park to change the lives of people in east London”.

“ABBA were attracted to the achievements we had delivered post-Games. Our vision, and their vision worked,” says Rosanna Lawes, LLDC executive director of development. “Arts and culture are fundamentally important to successful neighbourhoods… ABBA is an extension of that and an opportunity to expose and bring more venues to the park.”

There is also an argument to be made that placing this type of venue in an area in need of regeneration offers place-making opportunities: it can help boost existing businesses while creating hype around future developments.

“A temporary venue is a great way of adding or changing the character of a development because it’s associated with arts and culture, young people and that is all good,” says Alex Thomas, regional design director, sports & entertainment, at architects HKS. “It would be part of a wider mix you would do on any site to capitalise on investment and enhance it by initiating a draw factor.”

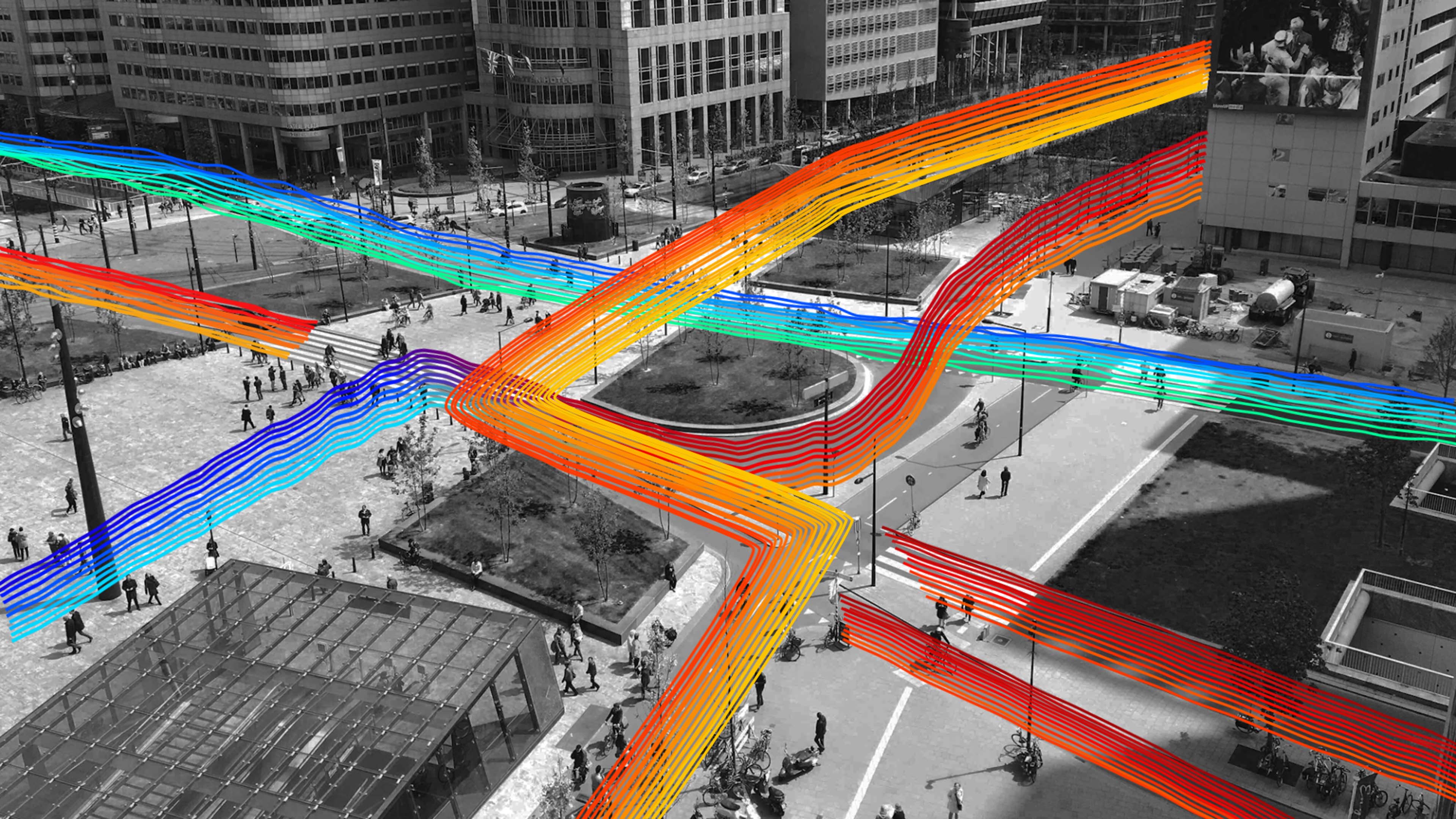

What also helped ABBA decide on the location of the arena was the site’s infrastructure. “That is a big factor in where you decide to put these demountable structures because people need to get there,” says Tkacz. “Bigger sites are normally out of town, where the infrastructure is usually not as good for transport.

“The positive about Stratford is its travel connections. Maybe no one has ever heard of Pudding Mill Lane station, but it’s right next to the site so people can get there easily.”

“A lot of developers are doing large-scale schemes, with 10 to 20-year plans meaning they have pieces of unused land while working on other parts of the site. This interim use is the perfect place to put these structures” Alicia Tkacz, Stufish

“A temporary venue is a great way of adding or changing the character of a development because it’s associated with arts and culture” Alex Thomas, HKS Architects

Acoustics is another issue. Despite the ABBA Arena being in a large area, it is surrounded by residents, so Stufish had to ensure the venue could be acoustically sealed. “The closer you get into the cities, the more stringent the regulations are on noise break-out. It’s always a balance,” says Tkacz.

If the arena is going abroad, then weather and geological climates need to be taken into consideration – such as if it’s a hot or cold country, susceptible to earthquakes, or rainy seasons.

“You must be zonal. The Europe version may have to be slightly adapted to go to America, or Asia,” says Tkacz. “Yes, the weather conditions will impact the design.”

Research on making demountable venues more portable is on-going. “The larger the structure and spans/heights, the more challenging it becomes to create a truly relocatable structure, as they typically require more permanent connections, such welding versus bolts,” says Darren Seary, FRICS principal of California-based Optimum Modular Solutions.

Stufish is working with fabricators on alternatives to building arenas from steel – the ABBA Arena used a hybrid steel and mass timber construction methodology – as metal can be impractical due to weight and cost of transport, especially when touring the world. Instead of using steel trusses, the fabricators are developing structural inflatable elements that can hold the same weight which will make them easier to move to sites.

And, as Tkacz explains, there should be opportunities to site these long-term pop-up arenas as they can almost be built into substantial projects. “A lot of developers are doing large-scale schemes, with 10 to 20-year plans meaning they have pieces of unused land while working on other parts of the site. This interim use is the perfect place to put these structures.”

The ABBA effect

At Stratford, the knock-on effect of the ABBA Arena to the area has been felt by the surrounding hotels, food and drink outlets and shops. Snoozebox is a temporary 80-bed hotel, made of shipping containers opened in July 2020. The website boasts it is: “Right next door to the custom-built ABBA Arena so only a hop, skip and jump away if you are heading to the concert that evening.”

A Snoozebox spokeswoman says: “The positive impact that temporary structures have in reinvigorating areas targeted for regeneration is very evident. This presents itself in terms of footfall, recruitment of local staff, contributions to local businesses.”

Europe’s largest shopping centre, the 1.9m sq ft Westfield Stratford City, is also on the arena’s doorstep. Alyson Hodkinson, general manager, and UK head of CSR at the mall’s owner, Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield, says the centre “benefits from increased footfall around music, sport, and cultural events in the local area… [which] benefits our retailers, restaurants and leisure and entertainment businesses.”

Tkacz says the project has meant Stufish is “now more mindful that it’s bringing people there who might live in the area in the future. And it is also drawing tourists out of the centre... [who] probably wouldn’t have gone to Stratford.”

Ultimately, for any artist, the show is what matters, and whether they need to create a nomadic circus. When 2027 comes and the 1970s Abbatars pack their virtual suitcases to head to the next city on their tour, the arena’s financial and logistical success will undoubtedly have inspired other entertainers to consider creating not just their own show, but their own venue as well.