-29-Mar?$article-big-img-desktop$&qlt=85,1&op_sharpen=1)

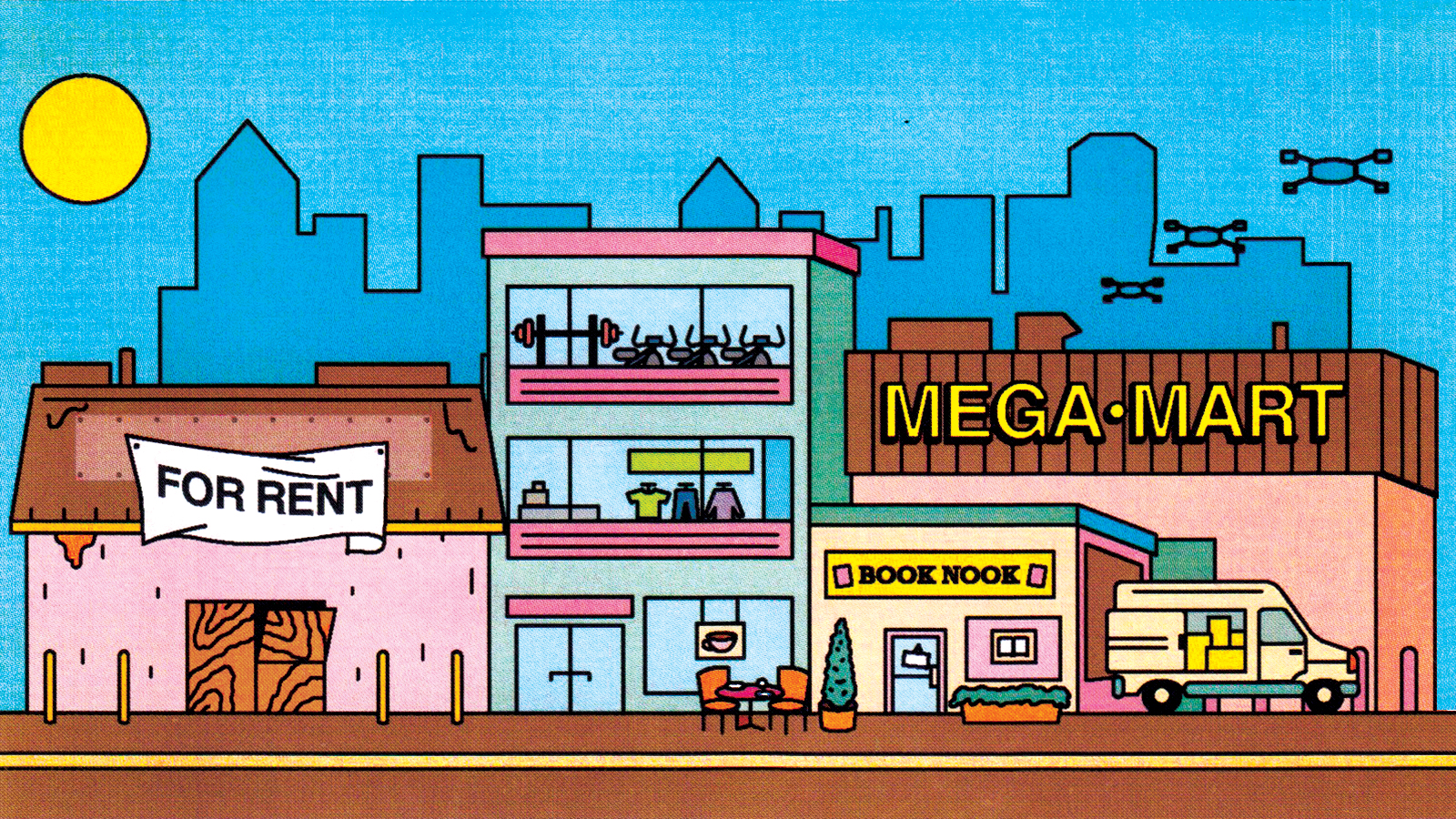

Illustration: Raymond Biesinger

There is a story David Harper FRICS tells those joining the retail agency Harper Dennis Hobbs (HDH).

“A long time ago,” says the firm’s chairman, “we acted for a coffee shop, which we offered to put in a newly-built Scottish city centre mall. We failed as the guy who was leasing it said he preferred Starbucks because his wife bought her coffee there. I said that Starbucks will not last in this city at £3 a coffee, and sure enough, they didn’t because residents could not afford it.

“But that was the perception of the owner of the centre: what his wife liked, the people of that city would like.”

It’s an example of landlord intransigence that makes many retail agents weep. But rather than depend on a landlord’s whims, today’s agents have a changing role from 20, or even 10 years ago - and placing retailers in shopping centres forms only part of their job. Over the past decade there has been a phenomenal rise in the food and beverages sector, alternative uses within centres, and the need to balance bricks-and-mortar shops with the exponential rise in online retails, which in the UK in January was shown to have climbed 74% year-on-year.

Fundamentally, however, whether they are acquiring agents, like HDH, or letting agents, their job and expertise, is to get the right operator, regardless of sector, into a scheme and to work collaboratively with the developer or landlord to help the centre’s success. And earn their fee.

How they do this is spotting the right tenant, having some sway over tenant mix, and keeping abreast of trends. Not easy in what was already a declining retail market before the pandemic struck. Lockdowns all over the world have affected retail: in many countries “non-essential” shops have been open only sporadically during the past year with stores in some parts of Europe having been closed more or less permanently since the new year.

The impact has been devastating. Figures released in February by the British Retail Consortium (BRC), for example, showed that non-food retail lost £22bn in sales in 2020 while data from the US projected a 60% loss in trade for department stores last year.

In the UK, the golden age of shopping centre development ran from the mid-1980s through to the beginning of the 2000s. Developers created out-of-town mega-malls, such as Lakeside in Thurrock, Essex; Metrocentre in Gateshead; Cribbs Causeway in Bristol, and Bluewater in Kent. Then there were the on-edge or in-town centres including the Westfield siblings at the east and west sides of London, Merry Hill in Birmingham, and the St Enoch Centre, Glasgow. The country was awash with retail space.

As time moved on, however, and the world entered the 2010s, new large-scale developments dried up, partly due to the credit crunch. Retail agents realised that consumers wanted more than just shops - they wanted an experience and they were insatiable when it came to food and leisure. Nevertheless, the basics of a retail agent’s decision in finding tenants, regardless of their sector, remained the same: “Understanding the demographics and the history of the place you’re going into,” says Harper.

Duncan Kite MRICS, managing partner at GCW, says he looks at the market segmentation: “Where does this client sit in that market, who are its competitors? Has it got a differential with those competitors, or is it just in the price? It also depends on whether it’s a start-up or more mature business.”

But they also rely on spotting trends. Kite draws from a wide international spectrum, paying particular attention to the US and emerging markets. He also follows commentators such as Steve Dennis, a strategy and innovation consultant, for updates on current consumer behaviour, how that is influencing what retailers are doing, and how retailers are responding to changes in technology. “But you see trends by keeping your eyes open,” he says, “and keeping them wide.”

For Richard Jones MRICS, director of retail and leisure at Avison Young, instinct is key. “We have been following many local food markets, witnessing these operators expand and take new units. Knowledge of such trends enables us to target and identify emerging operators for our clients.”

Risks on unknown tenants are still taken, however. “At a time when many multiple retailers are rationalising their trading portfolios, new independent and unknown tenants who have a compelling and relevant proposition can, to some extent, be the saviour of some of our shopping centres,” says Jones.

But mistakes can be made. “Everybody gets things wrong,” says Stuart Moncur, MRICS, Savills’ head of retail. “The world changes and the market moves or something happens out of your control. As advisers all we can do is influence within our control.”

Coupled with knowing the retailers, Moncur believes it is essential to know the actual centre. “You have to know everything about it. You can’t just send the retailer a plan and say, ‘Here you go, do you just want to pick a unit?’”

-29-Mar.jpg)

Dealing with an existing centre throws up its own challenges, as the scheme has an identity because of the tenants already there. “But they may not be the retailers people want, so that’s the opportunity to shape it in a different direction,” says Kite.

This throws into perspective the landlord/developer/asset manager relationship with the retail agent, and subsequently the retailers. Who has more sway over whom?

Graeme Jones, senior leasing asset and development manager, Sovereign Centros, which has Metrocentre, and Telford Shopping Centre as part of its 42-strong portfolio, says when looking at the process of getting in a retailer, it is they that set the agenda. “Ultimately, as asset managers, we set the business plan and formulate a strategy for tenant mix and alternative use strategies.”

In the past, says Moncur, developers and landlords used to be very prescriptive and would just tell tenants exactly what they wanted. Nowadays, dealing with a centre means having a vision of where he thinks it needs to get to, and what the reasons are for taking it to that point. “We advise clients,” he says, “and, if they agree, then we will try and execute that advice, so we do absolutely contribute towards the mix. Again, it goes back to advising the client on what we think is best, based on the research, and the other factors. Then you try and deliver it, but you also need the occupiers to come along with you.”

As to whether it has ever come to a conflict with the developer or landlord over particularly retailers, Moncur gives an emphatic “Yes! But that’s a healthy relationship with the client, when you can have those debates that you ultimately want to have, and then come up with the answer.”

For the past few years, a wave of empty units has flooded the market, with the on-going lockdown measures and subsequent business failures only adding to the supply. In December, Philip Green’s UK-based Arcadia empire collapsed – including the TopShop fashion chain which had branches across the world. It will add another raft of empty space: according to the BRC-LDC vacancy monitor, shopping centre vacancies in the UK were up to 17.1% in Q4 2020 from Q3’s 16.3%; in the US, Bloomberg predicts an 18% fall in retail property value as tenants shut up shop for good.

-29-Mar.jpg)

You see trends by keeping your eyes open, and keeping them wide

Given the shifting market, it is unlikely any vacant units will be filled with retail. Moncur advises on a major shopping centre in Glasgow, St Enoch Centre, which had a large anchor retailer Debenhams before the chain went bankrupt. He feels the space is unlikely to remain as big box retail in the future – another redundant department store in the shopping centre is set to open this spring as a Vue Cinema, with nine food and beverage units.

“Bringing in alternative uses is a big part of the strategy we put forward as part of our yearly business plans,” says Sovereign Centros’s Jones. “The agents have to be more flexible in how they look at that - you can’t just be a retail niche agent anymore if you are going to reach out and cover those voids with these alternative angles.

And flexible they are as the shift in the retail market hurtles to more mixed-use, meaning an evolution in the retail agent’s role.

“We need to change the way we approach clients, because we are not just brokers doing deals – that is very 10 years ago,” says Moncur. “We are advisers, and we need to advise clients on what they should and should not be doing. Or at least, what the options are.”

There have been many changes in the retail world, but the biggest and unforeseen upheaval of all has been the pandemic. Kite, an agent for 30 years, describes it as “both challenging, and interesting”.

“Booms and recessions are part of economic life,” he says, but “usually the reasons, and the route to recovery are clear. What we are seeing now, with the pandemic coming on top of what was already a declining retail market, is an acceleration of 10 years of retail decline that has happened in 10 months. It is not a managed decline that anyone is able to deal with: it’s an uncomfortable decline.”

The pandemic has not simply hastened the decline of bricks-and-mortar retail, it has taken some of our most beloved brands along the way. There have been, for example, discussions about building “COVID clauses” into new leases so that, in the case of another pandemic, both parties would share the pain in the form of a rent holiday or rent reduction.

But for everyone involved in the retail property sector, the hope must be a return not just to normality, but to some degree of stability.

-29-Mar.jpg)

The UK high street’s winners – and the losers

It has been a troubling few years for the British retail sector – some chains have survived, others have thrived but some of the oldest and most familiar have fallen by the wayside. Read full story