Photography by Jasper Fry

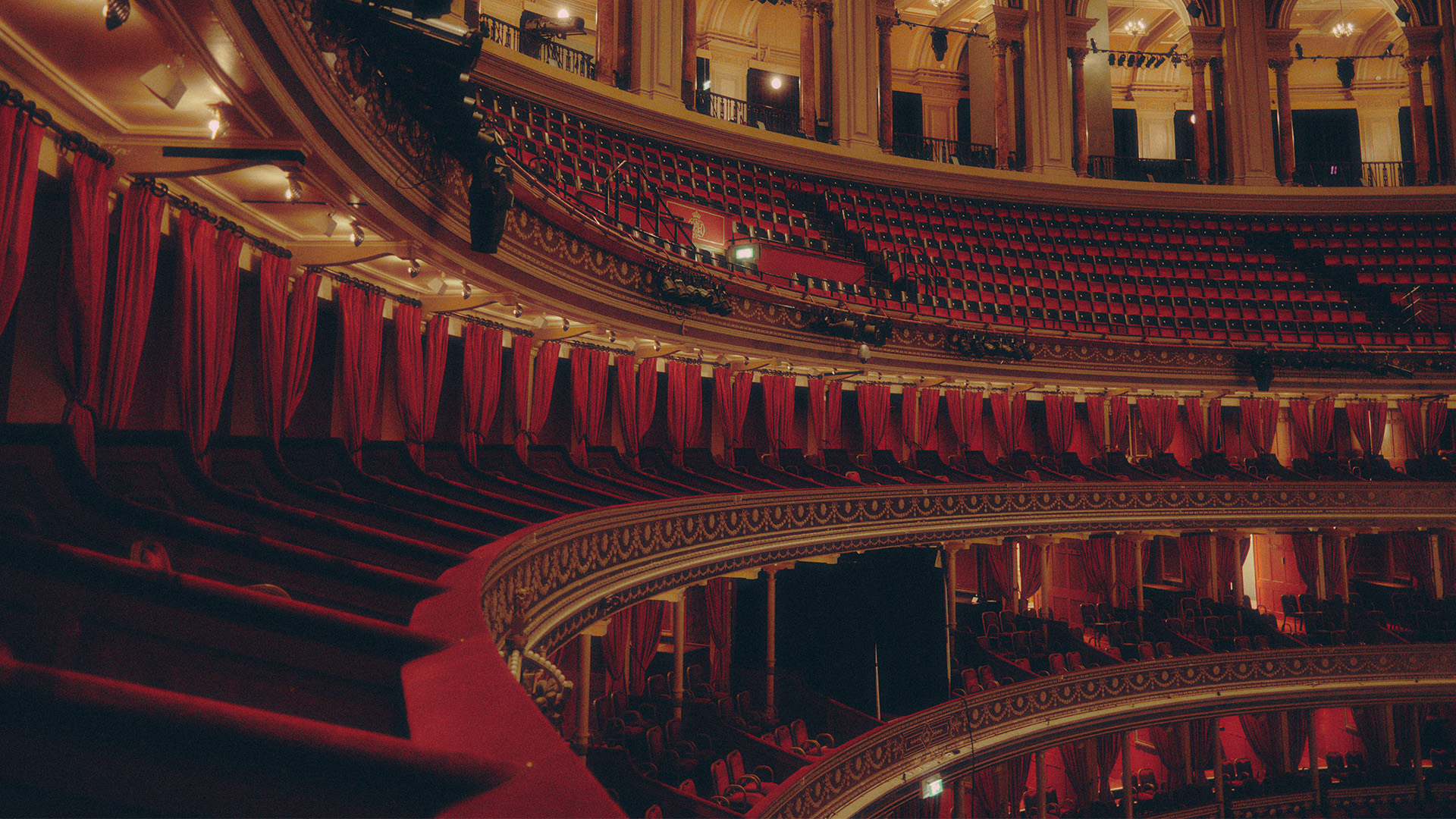

In November 2023, the Royal Albert Hall unveiled two pairs of sculptures. On the North Porch, made from Portland stone, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert gaze out over Kensington Gardens, occupying previously untenanted niches that have existed since London’s hallowed Victorian concert hall opened in 1871.

Meanwhile, bronze representations of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, depicted as they would have appeared in their 30s, adorn the South Porch.

The juxtaposition of Victorian and modern, together with the strong sense of continuity, embodies the task facing the professionals charged with maintaining the 153-year-old Grade I Listed building, while ensuring it continues to serve the needs of the artists and concertgoers today and in the future.

The storied history of the venue is an ongoing present-day challenge for its director of building and facilities, Neal Hockley. “The hall is a great place, but it’s quirky. Over the years it has undergone many developments, in both big packages and little make-do-and-mend gaffer tape moments,” he says.

Traversing the hall’s curving corridors, particularly in the crowded back-of-house areas crammed with flight cases, supplies and staff facilities, one is confronted by the most pressing difficulty that faces Hockley’s team: lack of space. It is a conundrum with its roots in decisions taken in the Victorian era. When it was built, the conservatory of the Royal Horticultural Society adjoined its south side.

“That provided the hall’s main public gathering space, but in 1888 it was demolished,” says Tom Gardner, a director at architects Allford Hall Monaghan Harris, which has been advising on projects at the Royal Albert Hall since 2018. “Since then, it has been a battle for space.”

South porch (below) adorned with the Queen Elizabeth II sculpture (above)

The show must go on

Maintaining the hall is an ongoing labour that requires judicious execution and meticulous decision-making, not least because any work takes place against the backdrop of a building in constant use by artists, the public, and its own staff. Receiving no public subsidy, the Council of the Royal Albert Hall relies on income from concerts to keep its doors open, so the show must always go on. In 2023, it staged 379 events in its 5,272-seat auditorium.

The last major redevelopment programme was carried out between 1998 and 2004, with the construction of the South Porch and the excavation of the basement to accommodate plant rooms, dressing rooms, and an underground loading bay. The next planned stage in its evolution was the ‘Great Restoration’ project.

“It was an extremely ambitious plan to completely renovate all the front of house spaces. There were lots of different strategies aimed at improving accessibility. We were going to have a rooftop garden and a champagne bar,” says project manager Alexandra Revell MRICS. “Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, and the hall had to close. That changed the financial situation, so we had a rethink, and that has led to the creation of our new estate plan.”

The plan outlines £73m of maintenance work and £261m of proposed capital projects over the next 15 years. It aims to diversify and develop the hall’s programme, audiences and engagement activities, strengthen its finances and operational resilience, enhance the visitor experience, and improve facilities for staff.

“Over the years it has undergone many developments, in both big packages and little make-do-and-mend gaffer tape moments” Neal Hockley, Royal Albert Hall

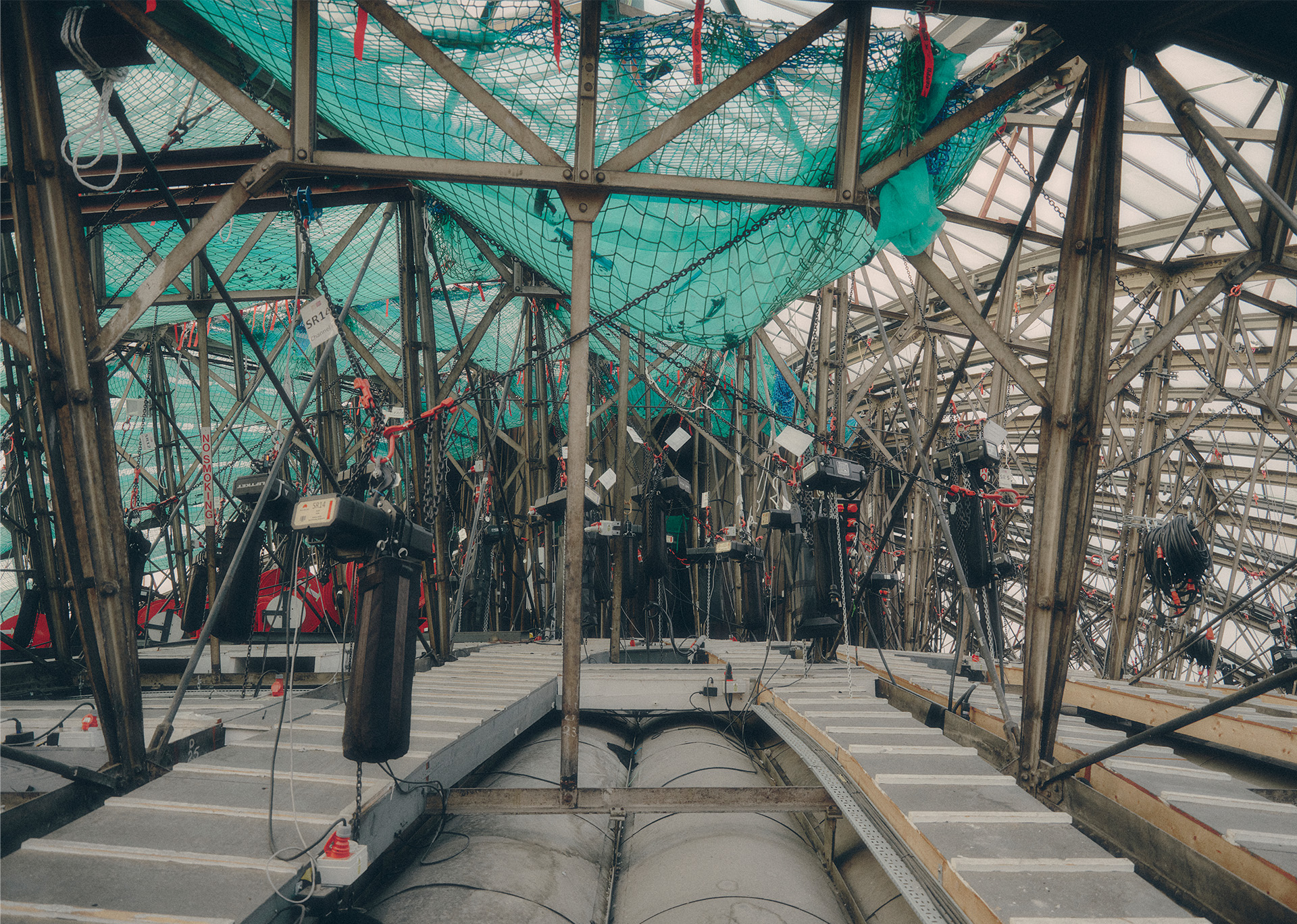

Inside the roof of the Royal Albert Hall

A scheduling puzzle

One of the chief complexities involved is the sequencing of multiple projects, which include creating an artists’ bar, relocating IT servers, creating a security control room, refurbishing seating and flooring in the auditorium, improving toilets, signage and accessibility, installing solar energy panels, rainwater harvesting and a green gallery roof.

Some will be paid for by charitable donations, but it is impossible to know which fundraising efforts will bear fruit first. With limited space available to perform a variety of functions, Gardner likens the process of moving activities from one space to another to enable work to be carried out to moving pieces around in a sliding 3D puzzle. The estates plan is designed to provide a flexible framework for the projects to be carried out.

Business cases will be produced for each project, and the feasibility of the capital programmes within the estates plan will be reassessed annually, says Hockley. Accessibility and sustainability will be addressed for each element. Meanwhile, a sustainability strategy is being developed, which will tie in with the estates plan. The building and facilities team is also collaborating with other South Kensington institutions to produce a net zero carbon plan for the neighbourhood.

A crucial preparatory step has already taken place with the completion of repairs on the hall’s 2,000m2 glazed-iron domed roof. Each pane of glass has been individually removed and either cleaned and refitted or replaced, while leadwork and iron downpipes have also been repaired or replaced.

Inside the hall's organ that contains 9,999 pipes

“There have been waves of building over the years, but essentially the hall has stayed the same” Tom Gardner, Allford Hall Monaghan Harris architects

With the dome watertight, conservation efforts can shift to the high-level plasterwork. Surveys have hitherto only been possible from above or below with the aid of binoculars. But the team has been working with specialist contractor Unusual Rigging to develop a purpose-built gantry, known as a “chariot” which will be capable of traversing the elliptical roof interior supported by the ring beams. In doing so, it will carry out more detailed examination and repair than was previously possible.

The chariot will also potentially be used to lift some of the largest pipes out of the organ for cleaning (the longest of which measures 12m,). A full-scale refurbishment of the giant instrument nicknamed ‘Jupiter’, which boasts 9,999 pipes, is planned, including the replacement of control modules, and the installation of safety rails.

The new archive will eventually be open to the public

The new archive

Within the bowels of the building, another major project has recently been completed – the opening of the new archive. Previously, historical resources such as construction blueprints, event programmes, records of committee meetings, and a variety of artefacts, had been stored in ad-hoc spaces throughout the building. Created out of a former dressing room, the new environmentally controlled facility will be open to the public later this year

Another major project sited below ground is an artists' bar that will provide refreshments to musicians and performers before and after shows, and in breaks from rehearsal. The venue will be fashioned from the shell of the former boiler house, which originally contained four Victorian steam boilers, before being converted to oil, then gas, and then relocated in 2010. The existing artists bar will become a dressing room.

Former boiler house and future artists' bar

“The pandemic changed the financial situation, so we had a rethink, and that led to the creation of our new estate plan” Alexandra Revell MRICS, Royal Albert Hall

The south-west basement is currently reserved as temporary space while functions are being relocated. But it will ultimately provide much-improved facilities for the hall’s personnel, some of whom must currently endure picturesque but cramped working conditions within the hall’s labyrinthine innards.

Near-term priorities for 2024 start with surveying the plasterwork in the auditorium, followed by refurbishment of toilets and a raft of health and safety projects such as replacing fire doors and improving balustrades on the south steps. “When you look at the estate plan you can see we are off and running already, especially with maintenance projects,” says Hockley.

Each of the multiplicity of projects is a contribution to preserving a great national treasure so that it can be enjoyed by generations to come, a small link in a long chain that connects the past with the future. “Recognising the sequence of layers and changes and how those are planted into the future is a big part of the estates plan,” says Gardner. “There have been waves of building over the years. But essentially the hall has stayed the same, occupying a consistent and unique place in London and the world.”

Fibreglass acoustic diffusers (nicknamed 'mushrooms') hang from the auditorium ceiling