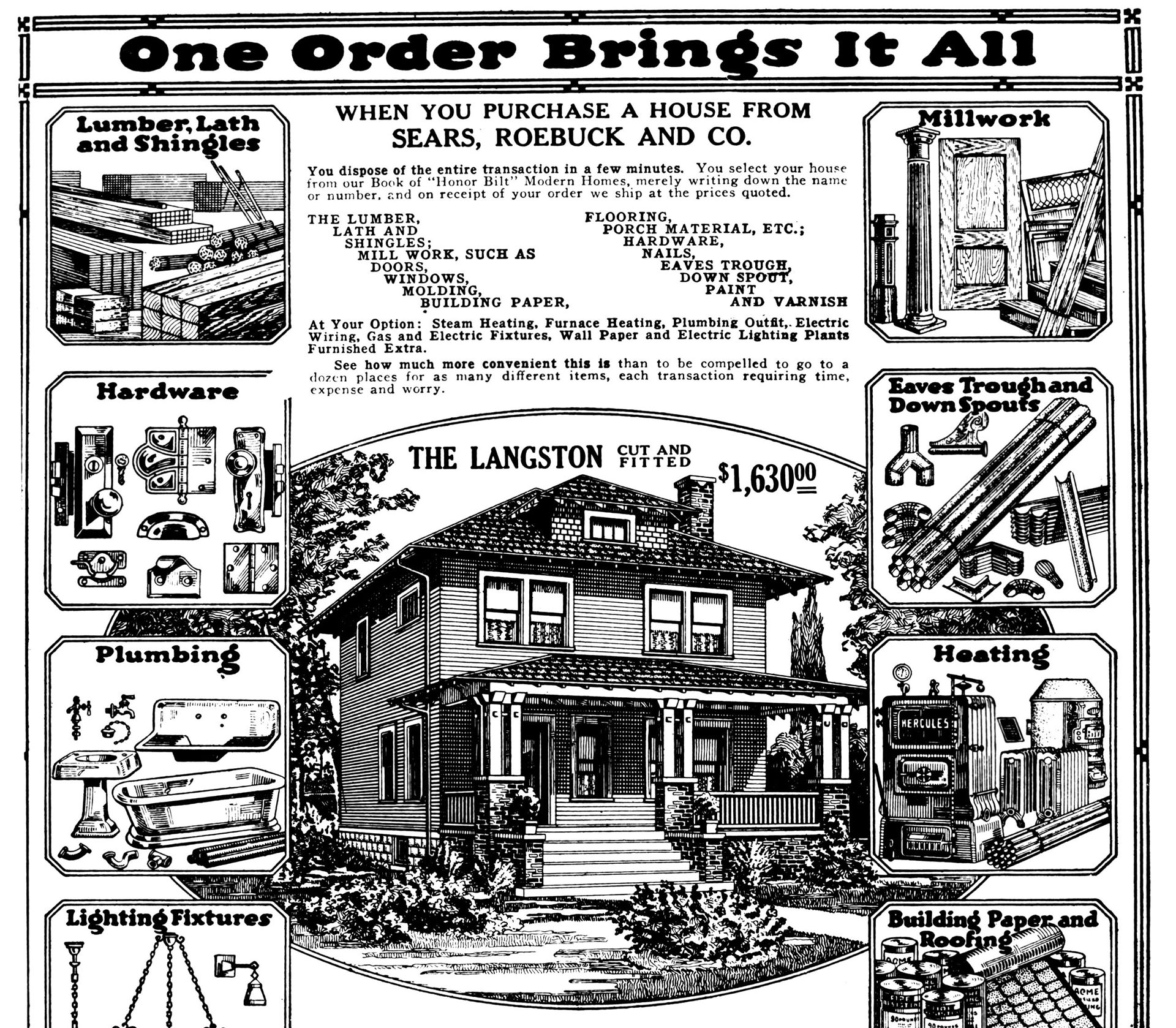

Over a century before Amazon.com proclaimed itself the Everything Store, US consumers could order just about anything they wanted from a Sears catalogue. The Chicago-based retailer shipped furniture, bicycles, household appliances, automobiles… and houses.

From 1908 to 1940, Sears sold some 70,000 kit homes that came in nearly 450 different designs. With precut lumber, doors, flooring, nails and paint, the handy buyer could follow the printed instructions to build a house from scratch much like a piece of Ikea furniture. Sears homes were affordable and well-made, and those still standing are prized in the property market.

Facing a housing deficit of 8.2m units (2023 data), the US today has a similar need today for low-cost, high-quality housing. Could something akin to the Sears model provide the answer? That’s the premise behind a number of new construction technology start-ups investing in prefabricated, or prefab, housing.

Prefab refers to any type of housing that is all or partially built off-site in a factory, then transported and assembled on site. Within that broad category, there are different styles, like manufactured homes – where the entire home is built off-site and can be placed on either a temporary or permanent foundation. And modular homes – which are built in pieces, or modules, off-site and then put together on a permanent foundation. In the US context, the former are built to meet federal code while the latter follow state, regional and local building codes.

In theory, the process is quicker and cheaper than building a similar house entirely on site from the foundation up. While the modern homebuyer or renter is far less likely to have construction skills than a turn-of-the-century newlywed farmer just settling down on the prairie like in the Sears catalogue era, the effect is largely the same: a limited set of options and less need for labour can streamline costs.

Between 1908 and 1940, 70,000 kit homes were sold through the Sears catalogue in the US

Cost-effective construction

Andrew McCoy, director of the Virginia Center for Housing Research, estimates that prefab can shave up to 10% off the cost of construction for new homes. In a market struggling with high interest rates and labour costs plus scarce developable land, those kinds of savings, if passed onto the buyer, can make housing more accessible for a broader swathe of consumers.

That’s been the common theme of cheerleading on the policy sidelines, from influential think tanks like the Urban Institute, Lincoln Institute for Land Policy and the Center for American Progress. The result is a rare note of bipartisan agreement with the public sector, in theory paving the way for private innovation.

Former US president Joe Biden unveiled a housing plan in 2022 that sought a revival in domestic home manufacturing. Later that year, the Biden administration’s Department of Housing and Urban Development hosted an annual housing showcase on the National Mall that included a range of prefabricated homes. In September, the second Trump administration hosted yet more new modular and prefab designs on display in the nation’s capital.

And yet, McCoy says, “They’re having a difficult time breaking through into the mainstream market.” Even with an annual production of more than 100,000 homes in four of the last five years (December 2025 results pending), at present prefab accounts for less than 10% of US market share in housing construction, but over 40% of the European market.

One of the biggest hurdles is local government. Building is a highly regulated industry with different rules per jurisdiction on issues like foundations, safety requirements and construction codes. For a prefab company to operate at scale, they must have access to a range of markets. But each new jurisdiction comes with pushback. “With anything new or innovative, you're going to see some resistance at the local regulatory level,” says McCoy.

“Prefab is like any other construction technique – there’s good, average and low quality” Scott Biethan FRICS, Cushman & Wakefield

Construction of modular apartments in the Netherlands. All components are prefabricated

Scott Biethan FRICS, director of valuation for the Pacific Northwest at Cushman & Wakefield, has seen this himself. He was recently advising a client seeking to build a luxury hotel resort on the Washington state coast using modular buildings, which flummoxed the planning department of a small, rural county. To move the project forward, a field trip may be in order. “We might need to take folks from a small town and send them to a factory in Europe where the modules are made just to get the officials comfortable,” he says.

While a high-end hospitality developer may have the margin for that kind of extracurricular lobbying, a homebuilder operating with limited startup capital and slim margins is unlikely to have an overseas site visit in their budget if they hope to keep homes inexpensive.

The other obstacle is stigma. In the US context, prefab carries negative connotations and conjures up images of mobile homes and trailer parks – housing typologies associated with low socioeconomic status. At their worst, older manufactured home communities are perceived as a type of rural slum.

But the new wave of prefab construction is far from trailer park stereotypes, offering everything from tiny homes to family-sized single-family homes to small apartment buildings that integrate into existing urban and suburban neighbourhoods. The architecture and design industry now issues awards and best-of lists for a once-maligned building typology.

Biethan advises his fellow surveyors to value prefab homes on empirical rather than socially determined merits. “Even though it’s more economical and costs less, doesn’t mean it’s of lesser quality,” he says. “It just means you are more efficient in the construction process. Prefab is like any other construction technique – there’s good, average and low quality.”

“With anything new or innovative, you're going to see some resistance at the local regulatory level” Andrew McCoy, Virginia Center for Housing Research

Puzzle Prefab is an award-winning prefab design that provides a carbon negative housing solution. It was created by Seattle-based design studio, Wittman Estes

Financial hurdles to growth

The buzz around prefab has also created a hype cycle for start-ups emulating the disruptive ethos of Silicon Valley tech entrepreneurs and produced some bumps in the road for the industry in the US. In 2021, the vertically integrated prefab housing firm Katerra, once valued at $4bn, filed for bankruptcy in a spectacular collapse.

There have been other less-high-profile examples of prefab companies going bust and leaving prospective homebuyers in the lurch, which has tarnished the reputation for a still emerging construction technology. On the financing side, the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau sued Tennessee-based Vanderbilt Mortgage and Finance in January for predatory loan practices. The agency dismissed the lawsuit in February.

Boxabl is the flashiest of the current contenders, with father-and-son CEOs Paolo and Galiano Tiramani racking up views for videos inside the company’s Nevada factory and demonstrations of folding homes that ship flat for easy transport. With catchy names like Casita for their flagship 361ft2 tiny home and Boxzilla for a planned factory the company claims will be the world’s largest facility for prefab homes, Boxabl has caught the attention of investors. In August, the company announced it would go public by the end of the year, with a $3.5bn valuation.

The public offering has opened up the company’s books, which appear shaky to analysts. Boxabl has only manufactured 744 casitas in its eight-year existence, with 285 delivered and installed by mid-August 2025. It recorded a net loss of just under $51m in 2024, and revenue of just $402,000 in the first half of 2025, which has led investors to question if Boxabl is really a start-up unicorn. A quarterly financial filing in August noted: “substantial doubt about the company’s ability to continue as a going concern is probable.”

While think tanks and industry analysts continue to believe that prefab technology has an important future to play in the US construction sector, they caution about companies aiming for hockey stick growth in a fickle industry built on slow change.

“There's so many entrenched special interest groups that have a say at different levels across the supply chain that can either veto or endorse these innovations,” says McCoy. “If you want to break through and vertically integrate … I haven't seen it really work yet. We’re a different industry, we’re incremental.”

The bold plan to increase housing in New York

Is a major shake-up of zoning regulations needed?