As our cities have grown and become more densely populated, the sewers have struggled to keep up with what we put into them. Fatbergs are a relatively new problem for underground sewerage networks to deal with – the term ‘fatberg’ (a portmanteau of fat and iceberg) was officially added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2015.

Use of the word fatberg has grown as quickly as the actual ‘bergs themselves – in extreme cases they have known to weigh more than 100 tonnes and measure up to 1km in length. While some of the most notorious fatbergs have been discovered beneath London, it’s a global issue with similar problems occurring in New York, Melbourne and Valencia. They are subterranean monsters living beneath the streets of densely populated cities, sometimes developing for a decade before they are discovered.

It’s an accolade London could do without, but it has become the fatberg capital of the world. The city’s sewerage system was a marvel of Victorian engineering when it was constructed in the mid-19th century, under the guidance of Joseph Bazalgette. But it was designed to serve a population of 2.5m and in 2021 London is home to just short of 9m people. The labyrinthine network of tunnels needs help, which is why the multi-billion pound Thames Tideway mega-project is underway to increase the city’s sewerage capacity and prevent overflowing sewage being spilled into the River Thames.

Once found, removal of a fatberg is no walk in the park. They become hard and dense and have to be chipped away with shovels and pickaxes or high-pressure water jets. They can be broken down into smaller pieces that float away to the nearest sewage works or they are removed manually with buckets.

Thames Water, which manages London’s water supply and disposal, dispatches teams of ‘flushers’ to deal with fatbergs late at night when the roads are quieter, because they need sewer access through manhole covers.

“These huge, solid masses can block the sewers, causing sewage to back up through drains, plugholes and toilets,” says Anna Boyles, operations manager at Thames Water. “It can take our teams days, sometimes weeks, to remove them.” In short, they are an environmental and logistical nightmare.

What's in a fatberg

To understand how to deal with the problem of fatbergs, it helps to know how they are created in the first place. While non-degradable wet wipes being flushed down the toilet are partly to blame, the other building blocks of fatbergs are nothing new, says Boyles.

“Pouring fat and oil down the kitchen sink has always had the potential to cause blockages, but it wasn’t until wet wipes began to be marketed as a luxury alternative to toilet paper in the early 2000s that the problem became much worse,” she says. “If fat is the mortar, wet wipes are the bricks.

“These blockages are slow-growing and can take years to get to headline-grabbing proportions, but by 2010 we were starting to see the rise of the fatberg in London.”

And if you are wondering what a years-old mass of congealing fat smells like, Boyles adds: “Fatbergs are rancid. The smell has been compared to festival toilets and rotten meat. Our fatberg-busting team typically wear gas masks and rubber suits and carry monitors that continually check for harmful levels of combustible gases.”

James Barker is a professor of analytical science at Kingston University’s Faculty of Science, Engineering and Computing. He has analysed the composition and chemistry of fatbergs, learning more about how they are formed.

“In general, fatbergs contain four main chemical components: calcium, free fatty acids, FOG (fat, oil or grease) and water,” he says. “[That combines with] other items that do not break apart or dissolve when flushed down the toilet, such as wet wipes, sanitary towels, cotton buds, needles, dental floss and condoms, as well as food waste washed down kitchen sinks.

“Fatbergs form at the rough surfaces of sewers, where the fluid flow becomes turbulent. This can happen when tree roots break through into drains or when there is damage to the brickwork of London’s Victorian sewage system.”

Cooking oil may go down the sink in a liquid state, but it cools and solidifies in the sewers below. And while the finger has often been pointed at areas with high concentrations of restaurants, Barker says that around three quarters of the oils, fats and grease in sewers come from domestic sources.

“For instance, lipids [found in hair conditioner] contain fats (triglycerides) that have congealed through cooling and have undergone a process of saponification. This is where the fat reacts with the alkaline mortar lining of the sewers, turning the oil (principally palmitic acid from animal fats, sunflower oil and dairy products, as well as oleic acid from animal fats and olive oil) into soap-like substances (fatty acid salts). It’s ironic that cleaning products, such as hair conditioners, are part of the blockage problem.”

Turning fat into fuel

It would undoubtedly be preferable if fatbergs didn’t exist at all, but every coagulated cloud has a silver lining. It’s estimated that by removing the oil from London’s fatbergs, more than 130 gigawatt hours of energy could be produced a year – enough to power about 40,000 homes.

However, as Barker explains, to do this efficiently and on a larger scale, it would require wastewater treatment to be decentralised. “Turning fatbergs into biofuel has been tested,” he says. “But we need more localised ways of collecting household waste so that it doesn’t have to travel so far to a central facility and it remains more concentrated.

“Tankers could collect fatbergs from processing plants and sewers and transfer them to a specialist plant. They would be heated to melt the fats and solids and water would be removed using a high-tech filtering system. The treatment company would then syphon off a fairly clean oil, to which various chemicals would be added to produce biodiesel.”

Fascinating and revolting

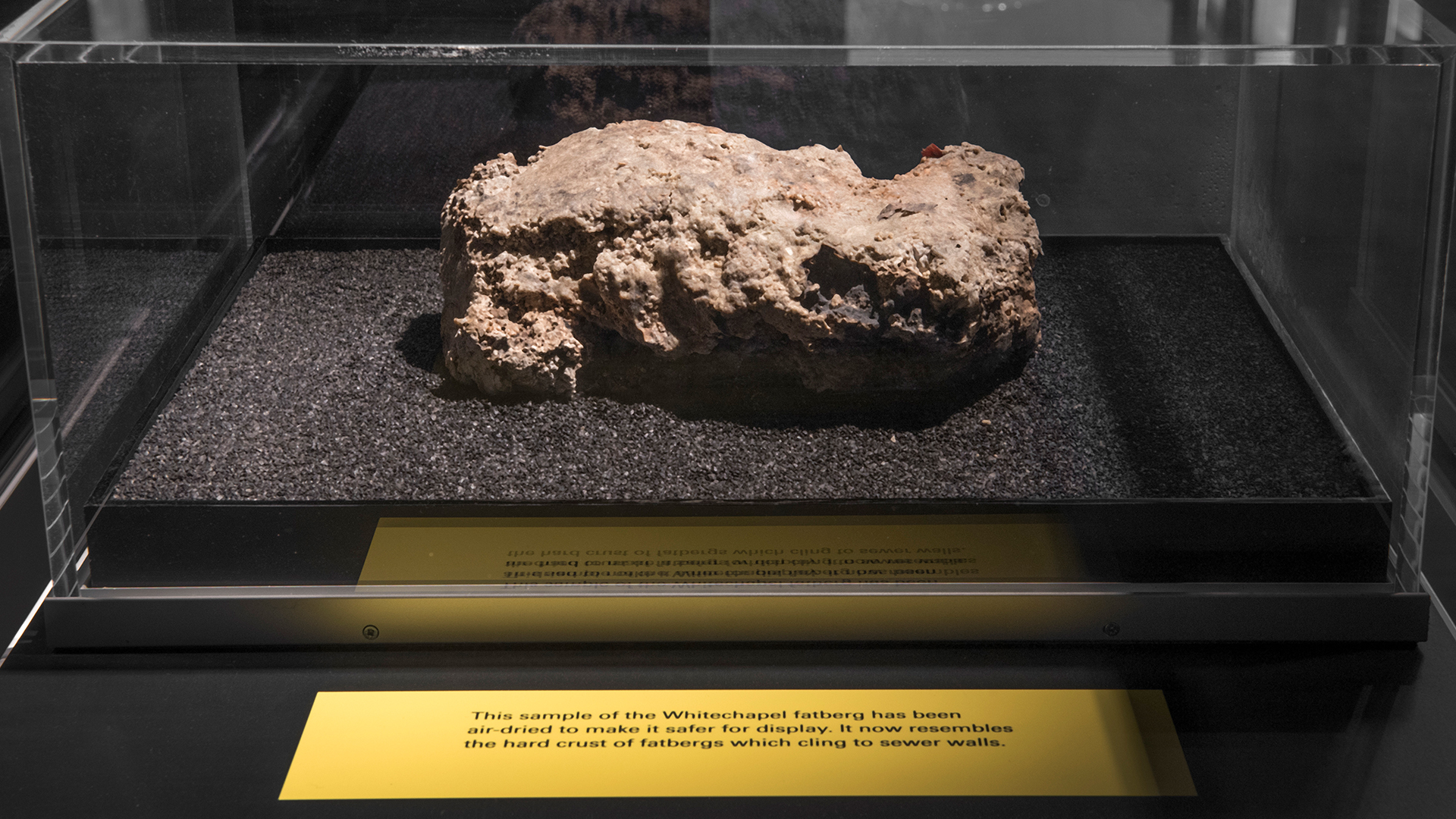

In February 2018, the Museum of London (MoL) opened what was to become an incredibly popular exhibition featuring a piece of the Whitechapel fatberg, known as the ‘Monster of Whitechapel’. The rugby-ball sized piece of fatberg was encased in a specially sealed unit, which then went inside a display case and told a tale of London that many of its residents and visitors would rather not think about.

Barker says he thinks the popularity of the MoL exhibition was “because the public are both fascinated and revulsed at once. It’s a monster from the depths of our sewers, it shows our disgusting side! A microcosm of urban life, our infrastructure and our habits. There’s a bit of all of us in it.”

“It’s a monster from the depths of our sewers, it shows our disgusting side.” Professor James Barker, Kingston University

Fighting fatbergs

Stopping fatbergs forming in the sewers is a huge challenge, part infrastructure project and part public information campaign. Do we try to upgrade sewerage systems to the point where they can cope with anything we chuck at them or is that just further enabling a minority who continue to flush wet wipes down the toilet and pour gallons of oil down their sink?

“In West Ham and Harlesden we’re pioneering the next generation of ‘sewer level monitors’, which send data to help us pinpoint emerging problems before they grow into something more serious,” says Thames Water’s Boyles. “We will always invest in infrastructure, maintenance and technology to improve the resilience and performance of our sewer network.

“We’ve also worked with more than 2,000 restaurants, pubs and other food service establishments to help them install effective grease management in their kitchens, which capture fat before it can get into the sewer.

“However, spreading the word about the devastating impact of sewer blockages and encouraging everyone to help us ‘fight the fatberg’ is arguably the most effective weapon in the battle against these subterranean monsters. If we can stop the problem at source, we take away the raw ingredients needed for a fatberg to form.”

“Fatbergs are rancid. The smell has been compared to festival toilets and rotten meat.” Anna Boyles, Thames Water