The rise of flexible working during the pandemic may have been anathema to some stiff collared bosses, but it has made life profoundly easier for millions of workers who have been liberated from the traditional nine to five.

It also seems that the pandemic may well have a lasting, positive impact on the way in which we plan and operate our cities. Specifically, the last two years has seen the proliferation of the 15-minute city concept, according to its originator and chief proponent, professor Carlos Moreno.

The idea also becomes more appealing as climate change awareness increases. It is already evident that extreme weather events have become noticeably more frequent – and better reported – in recent years. “We need to develop a more local economy, more local activities, to develop a more sustainable way of life,” says Moreno.

Famously, Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo made the 15-minute city concept a central plank of her 2020 re-election campaign in 2020, making Moreno a celebrated figure, at least in urbanism circles. But it does now seem that the idea is being embraced in countries with very different attitudes to urban density, not least the US, which is notorious for its car dependency.

Crossing the Atlantic

Moreno isn’t naive about the challenges involved in applying the model to many US cities, but he still believes it is possible. “Of course, you have North American cities such as Los Angeles that are very spread out,” he says. “This is hard to change. But there is a real possibility for changing the mindset and developing these new kinds of policies.”

Perhaps the most prominent example of an American 15-minute city is to be found in Utah, where a project is being brought forward to replace the Utah State Prison in Draper with a new community known as The Point. The prison is due to be demolished imminently and the redevelopment of the 600-acre site is set to include affordable housing, community facilities, employment space and more, all designed around Moreno’s concept.

In July, The Point of the Mountain State Land Authority selected Lincoln Property Company, a national developer, and their local partners Colmena Group and Wadsworth Development Group to bring forward the first phase of development. Infrastructure works are expected to begin hard on the heels of the prison’s demolition.

CG Images of The Point, Utah

“The Point represents the single largest development site in the country in recent years,” says Abbey Ehman, vice president at Lincoln. “[The project] is an innovative, community-centric development that uses sustainable, transit-oriented solutions and celebrates the area’s natural beauty.”

By keeping jobs and homes closer together, Alan Matheson, executive director of The Point, believes that they should be able to reduce traffic movements in the area significantly compared to local norms.

“There are plans underway to develop a transit line through the site and down into Utah County,” he told local radio earlier this year. “We’re also looking at internal circulators that would get people within a five-minute walk of any place in the site. There’ll be car-sharing and micro-mobility to go to different hubs, where you can continue your journey on a scooter or an electric bike. We’ll reduce traffic generation by more than 30%.”

What is a 15-minute city?

Moreno coined the term back in 2016, the year after – and in response to – the COP21 meeting in Paris. The idea is simple enough: that cities should be planned in such a way that all citizens’ day-to-day needs should be accessible with a 15-minute walk or cycle ride. That includes access to education and healthcare, but also work and shopping. The aim is to instil a stronger sense of community and massively reduce vehicle movements, thereby cutting carbon emissions.

According to Moreno, the idea attracted significant interest from the outset, but also prompted a sceptical response in many quarters. “It’s about living differently, reducing long commutes, developing multi-purpose buildings and more local activities,” he says. “But when I proposed this concept, some people said ‘this is very nice but it is a utopian idea because the most relevant activity for people is working and it's not possible to work [so locally]’.”

“It’s a city of neighbourhoods, so there are already these clusters of services throughout the city,” University of Washington landscape architecture professor Jeff Hou said recently. “It’s not like LA, where the density is so low, things are so far apart from each other that you have to drive. There is sort of an urban fabric in Seattle.”

Seattle leads the way

The 15-minute city concept is also being embraced in a very different context in Seattle on America’s north-west Pacific coast. In September 2020, the city’s Office of Planning and Community Development announced it would consider the 15-minute city concept as a potential guiding principle for the next version of its comprehensive plan.

Then the pandemic struck, a global shock that put it beyond doubt that yes, a huge variety of work could indeed be done as locally as the kitchen table. As a result, Moreno says, the 15-minute city spread around the world effortlessly. “Because of the pandemic, the concept was adopted in almost all continents,” he says.

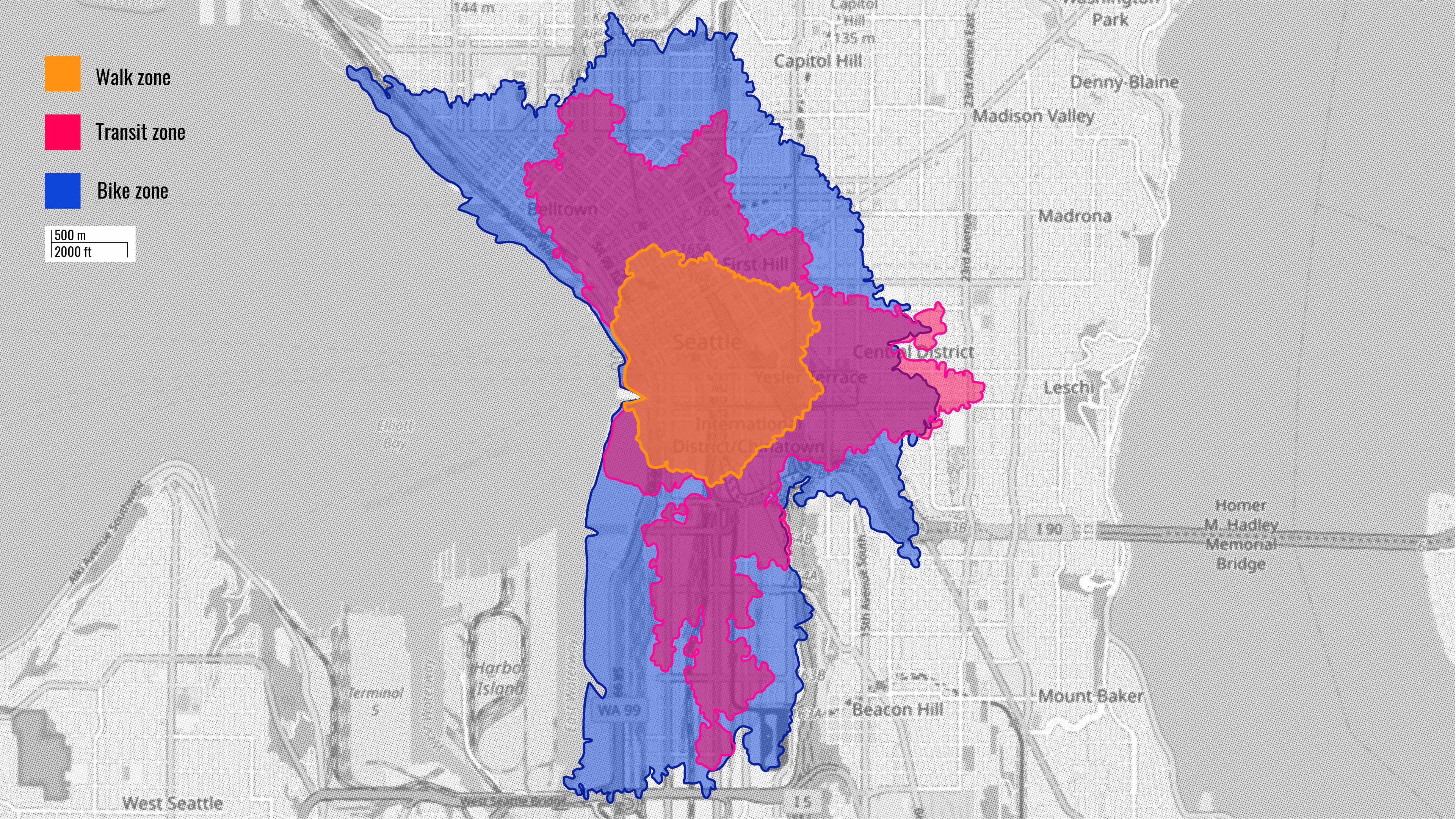

This map depicts how far people can travel by walking, cycling, and public transport in 15 minutes from downtown Seattle. Data taken from TravelTime. To see if you live in a 15-minute city, check out Here. Map © OpenStreetMap

It’s an aspiration helped in no small part by the fact that Seattle is currently investing heavily in public transport. “When you have urban core areas that are well served by transit, you can see this kind of a city planning and growing around that,” says Scott Biethan FRICS, senior managing director, Cushman & Wakefield.

“We have some areas that are well served for the 15-minute concept. And our inner light rail is expanding, so you can see a lot of development occurring around new transit. It becomes a lot more intentional. You can have environments that are much better for walking.”

The 15-minute city may have been born out of a specific urban context, but it is proving adaptable in countries even as wedded to the car as the US. And that, it is clear, is being super-charged by the legacy of the pandemic and the ever-growing threat of climate change. Quite simply, we need to change the way in which we work, live and play.