Illustrations by Carl Godfrey

A dynamic city-state known for its innovation and efficient urban development; Singapore faces tough physical constraints due to a severe lack of land needed to service a constantly expanding population.

Its population rose to a historic high of 6.04m last year, mainly due to an influx of non-residents. It’s a significant hike on the 4.27m citizens it had in 2004, and there are precious few undeveloped sites within the 734km2 territory left to deliver housing and employment.

The single largest area still available for redevelopment is the 800ha Paya Lebar Air Base (PLAB), and authorities are currently working out a strategy to transform the site when the military leaves in 2030.

Due to be completed in phases over two to three decades, the project would include some 150,000 homes, potentially housing almost half a million people, as well as zones for employment, retail and leisure, and improved connectivity between the north-east and east regions of the island currently separated by the airbase.

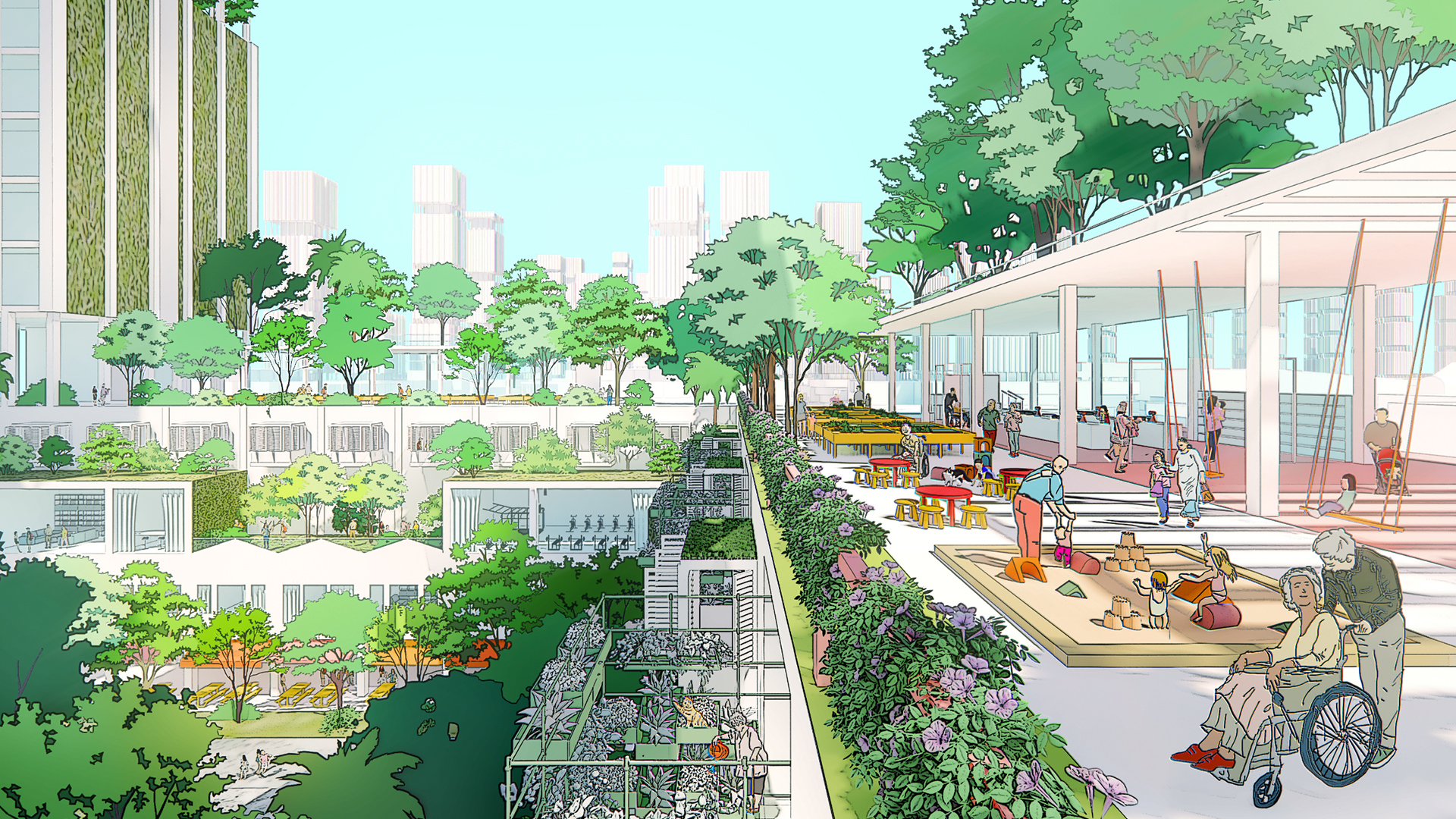

A complicating factor is that key existing features, such as the 3.8km-long runway, PLAB’s control towers and bunkers, will all be retained to pay homage to the site’s history as a former international airport. On top of that, advanced concept design studies for the redevelopment, developed by members of Singapore Institute of Planners (SIP) and Singapore Institute of Architects (SIA), include a target to reserve 30% of available land for green and blue space, something previously unheard of in Singapore.

“If PLAB is built, it will have the largest amount of open space and water features of any new town in Singapore,” says Jason Ho, former RICS North Asia MD and part of the design team at SIP. “That 30% only accounts for the major parks. Smaller plots and green spaces will add another 10%. We want to ensure everyone has access to a green or blue space within five minutes walking distance.”

Blue sky thinking

Plans for PLAB have been in gestation for a while. In 2021 Singapore's national planning authority, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), launched a public consultation on how the land should be repurposed over the next 40 to 50 years to optimise sustainability, self-sufficiency, and pandemic readiness.

URA appointed members of SIA and SIP to develop a concept master plan, and the team was subsequently divided into two smaller working groups to go into greater detail at an urban design scale.

According to Tan See Nin, senior director of projects in the physical planning department at URA, despite its density, PLAB represents a “vision for a highly liveable and sustainable town of the future … the equivalent size of two new towns with many new workplaces and amenities.”

Historically, Singapore was centralised around its business district, but urbanisation has, over the ensuing decades, transformed its outlying areas, known as the heartlands, into new towns. In the early 1990s, a drive to bring higher-paid jobs closer to homes and reduce traffic congestion, saw distinct centres established in five key regions.

PLAB is situated close to a centre in the East Region, and not far from the 50ha Punggol Digital District which is due to open later this year. According to Ho, this caused some debate over whether another major new town was required. Nevertheless, the benefits of bringing jobs closer to residents, cutting travel times and reducing congestion were seen as major advantages.

At the highest level, the concept master plan aims to reimagine what a future community in Singapore should look like. The common impression of Singapore may be of a clean, well-organised and innovative city, but underneath this veneer, there are issues with over-urbanisation, overcrowding and a stressed workforce.

“Planning projects typically consider how many people to house or how much commercial space there should be.” says Ho, “But with PLAB we wanted to think about how to create a physical environment that addresses issues like wellness, general wellbeing and resilience, not just in terms of extreme climate and biodiversity, but in terms of human relations and community building.”

“Planning projects typically consider how many people to house or how much commercial space there should be.” We wanted to create a physical environment that addresses issues like wellness, and resilience, in terms of human relations and community building” Jason Ho, SIP

Concept designers wanted to create a town where the aspects of “live, work and play” are in balance and social, economic and environmental considerations are all considered.

Aside from new housing, employment and commercial areas, PLAB will feature multiple sites for sport, recreation and leisure. Its car-lite approach will further encourage healthy and active lifestyles with a preference for walking and cycling in its neighbourhoods. In addition to two mass transit rail stations, parking “hubs” will be located 400 to 600 metres away from where people work and live, instead of the current practice of building large basement or multi-storey car parks. An autonomous vehicle loop will connect the entire district.

Singaporeans are proud of the city-state’s Park Connector Network, a network of linear green corridors developed by Jason Ho in a 1991 concept plan, that link major parks and nature areas across the island. The PLAB plans propose the airbase’s runway would act as both a central spine for the new town and a “green connector” community space extending from one end to the other. Furthermore, various water features would help the new town deal with increased rainfall resulting from climate change.

“Not only will the new town contain the perfect balance between public and private housing, but the airstrip will act as a natural air corridor and ‘green lung’ for the new town,” says Bill Jones FRICS, a Singapore resident and global head of workplace & corporate real estate at Maxeon Solar Technologies. “The new town will also create space for businesses, which means employment opportunities, further enhanced by the necessary construction activities.”

Land use remix

A former British colony, Singapore has tended to zone land in sectors such as residential, commercial, industrial or leisure. However, in the modern context of land scarcity and extended travel times between areas, PLAB proposes an innovative mixed-use approach better suited to contemporary urban lifestyles.

This would apply both horizontally, and vertically. “We wanted to challenge the typical two-dimensional land use classification for a building,” says Calvin Chua, a project architect for the concept masterplan and founder of design consultancy Spatial Anatomy.

The first-of-its-kind vertical zoning concept would see, among other things, industrial estates integrate activities, such as industrial uses and co-working spaces, with residential spaces on the lower, mid and upper floors, helping increase housing supply in a more land-efficient way.

The runway will be divided horizontally, public squares, and lower rise development would engage people in different ways as they move along it. Different stretches will have a different character depending on the mixed-use theme of the adjacent development, whether commercial- or residential-oriented.

This is all a radical departure from the existing Paya Lebar Airbase, which features many buildings dating back to 1954 when the then-Singapore International Airport was built to replace Kallang Airport.

Designers want to “redefine what it means to adaptively reuse existing pieces of infrastructure and not just erase everything and start from scratch,” says Chua. That means not only refurbishing the control tower and main terminal building, which are already earmarked for heritage conservation status, but expanding the definition of heritage to include “everyday heritage,” such as hangars and bunkers, which bring an “everyday value” to life in the city.

Heritage buildings would become anchor points for each precinct in the development’s 200ha Old Town area. The terminal building, with its double height spaces and interesting architectural features, would provide space for a museum; hangars would be turned into flexible spaces for research and innovation, like digital fabrication laboratories.

Investment opportunity

The decision to shift the airbase away from the site has already sent positive signals through the local property market, catalysing redevelopment in the surrounding regions of Marine Parade, Hougang and Punggol.

Lifting height restrictions when the airbase use is phased out is “expected to benefit both the airbase site and surrounding land,” says Tan, helping build on growing interest in the new town concept and its more relaxed ethos.

Plans for the PLAB site remain in their infancy, however, and, in the run up to 2030, “will need to respond to the evolving social, economic and environmental needs of the nation, including Singaporeans’ aspirations over time,” says Tan.

More concrete proposals for the project are expected to come later this year when URA publishes an updated master plan review for the whole of Singapore.