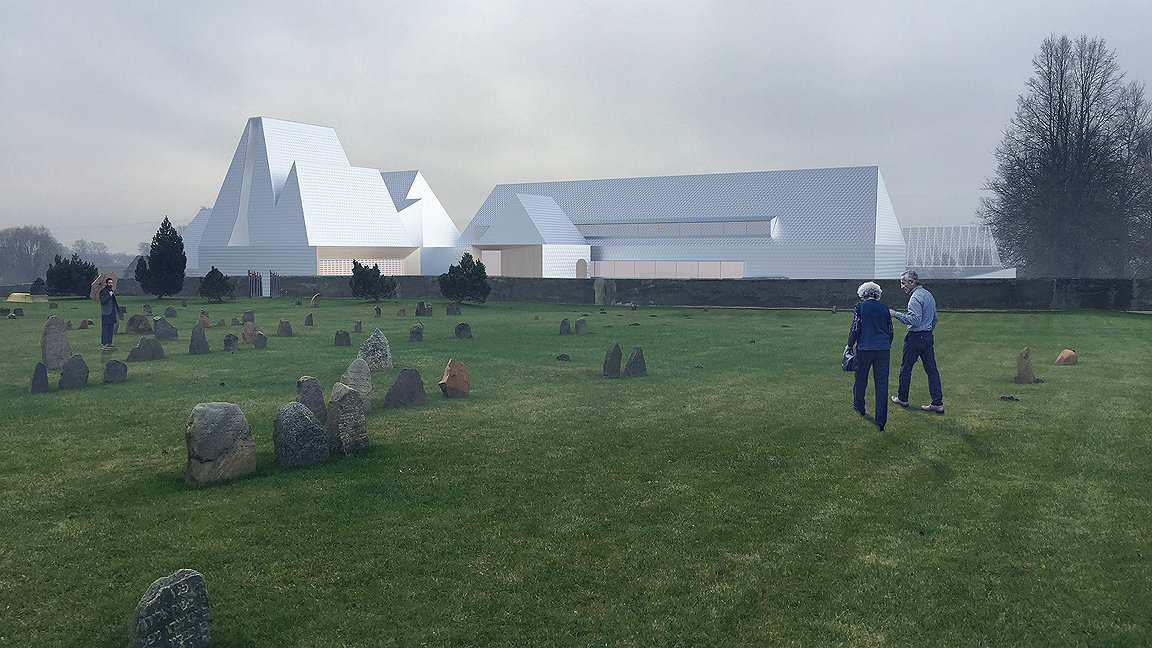

A CGI render of what the Lost Shtetl museum will look like

David Duffy FRICS has been an involved member of RICS for 50 years. In fact, his membership began on 8 November 1971, the same day Led Zeppelin released their untitled fourth album featuring the single Stairway to Heaven.

His career as a chartered surveyor started in the UK, with Ridge and Partners, before he spent 10 years in Africa working on projects ranging from game lodges in South Africa to a cement factory in Nigeria. He also worked in Baghdad as a deputy project manager during the Iraq-Iran War in the early 1980s, sent there to stop work on a job that Saddam Hussein was not going to pay the contractors for.

In 1987, Duffy formed Ecas AG in Zurich, Switzerland and has been based there ever since. Leap forward 34 years and today he’s project managing the Lost Shtetl museum in Seduva, Lithuania. ‘Shtetl’ is the Yiddish word for small town and the museum is a monument to the Jewish people of Lithuania, living in such towns, who were killed during the Holocaust.

Modus caught up with David ahead of his 50th anniversary as a member of RICS to find out more about the museum and the challenges involved in working on a historically significant project.

What is the Lost Shtetl museum project and why was Seduva chosen as its location?

We got involved with the project in 2016. The architect for the building design is Lahdelma & Mahlamäki Architects from Finland, who did the Warsaw Holocaust Museum. In the early days of the project, Rainer Mahlamäki told me: “A museum project always takes seven years” because of all the angles to consider, from the sponsors to the people who are going to run the museum, design the exhibitions and construction of the building itself. Seven years sounded about right to me and that’s what we will have taken if it opens in 2023.

The location is Seduva because the sponsors have family heritage in that region, where there were a lot of shtetls. There are two foundations involved in this – the Lithuanian Foundation (SZMF) and a Swiss organisation that does a lot of work with Jewish communities in eastern Europe.

Seduva isn’t really a place that’s on the tourist map but there are two areas they are hoping to get visitors from: one is the Jewish diaspora, for whom it will be very special and unique. It’s also on the tourist route from Vilnius to Riga, Latvia so it could well be a stop-off for tourists of all nationalities.

Shtetl’ is the Yiddish word for small town and the museum is a monument to the Jewish people of Lithuania, living in such towns, who were killed during the Holocaust.

How has the museum been designed?

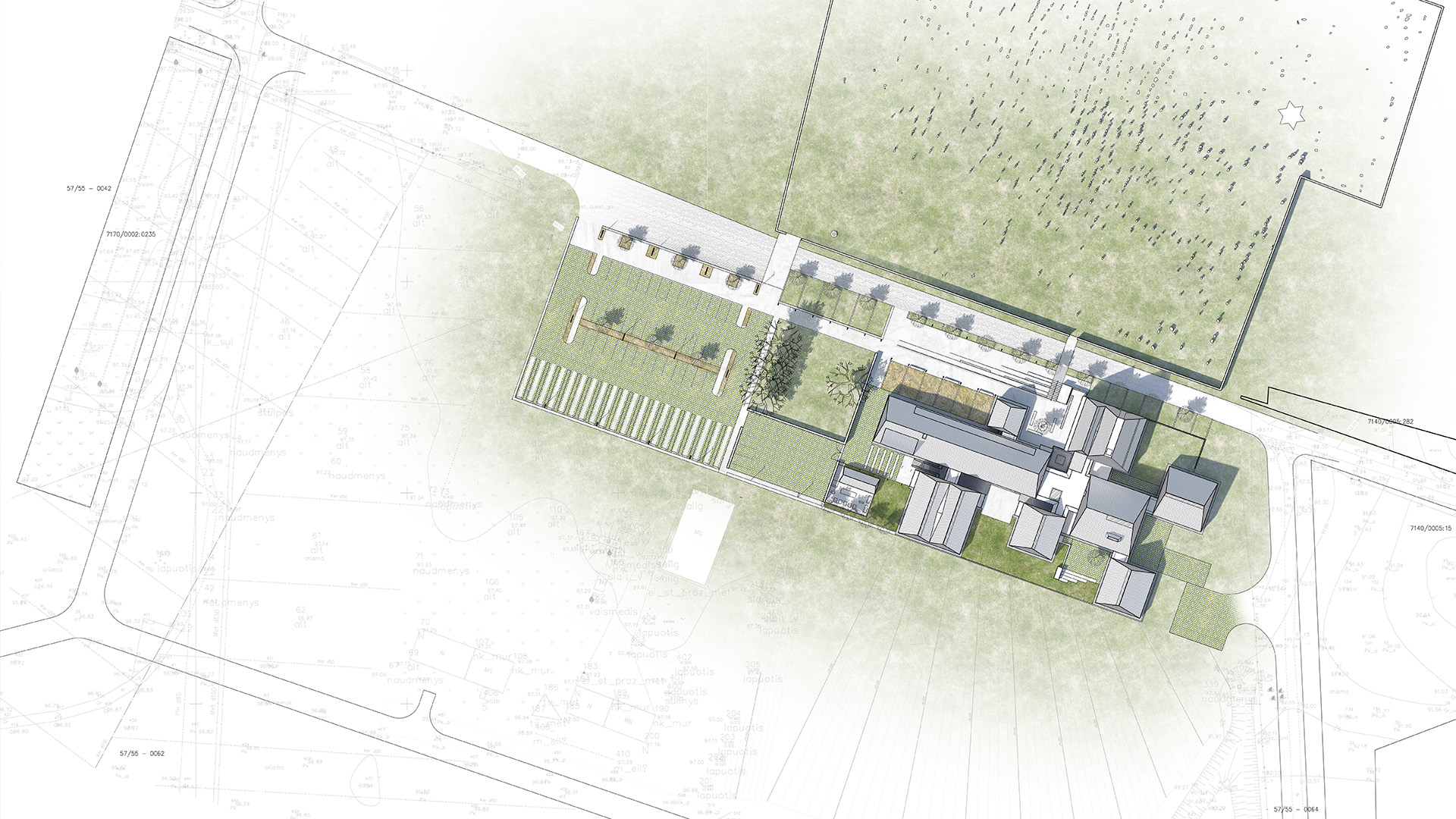

The architectural concept of the museum is a cluster of different buildings to represent the cluster that a Jewish shtetl would have been composed of. Once you’ve been into the admin building, you go down into the first gallery. The biggest gallery in the middle that you always go through is the marketplace. Then there are various galleries along the way, the voices gallery, the synagogue. Then you get to the final gallery, which is the Holocaust gallery that climbs up eventually to the top floor called the Canyon of Hope. And then you end up looking over the renovated cemetery.

The early galleries are about conveying what Jewish life and culture was like in the early 20th century. Then the Holocaust gallery will show the impact and very dramatic effect of a lot of Jewish people being killed very quickly in that area of Lithuania during the Holocaust, partly because of the collaboration of non-Jewish Lithuanian people with the occupying forces.

There’s an Economist article on the subject, which goes into more detail on the “widespread collaboration” of the Lithuanians who helped round up and murder Jewish people. Around 90% of the 250,000 Jews living in Lithuania at the time were killed, one of the worst rates in Europe.

The prime minister [of Lithuania] told the press after a visit to the site that it’s something the country still hasn’t owned up to – these basic facts of the Holocaust in their country.

What’s your involvement in the project?

We project manage the building, but not the exhibition inside. On the one hand we look after the building project for the sponsors, and on the other hand we have full power of attorney from the Lithuanian Foundation to run things for them, managing a team of Finnish design architects, Lithuanian engineers and contractors and of course coordinating all the building work with the American exhibition designers in New York.

What were the biggest challenges you faced in the design and building of the museum?

The Finnish architect is doing a contemporary interpretation of a cluster of shtetl buildings. All the buildings are different sizes, all the roof shapes are different. Even the concreting of some of the roofs is very challenging for the Lithuanian contractor because they’re so steep.

We have Fins, Estonians and Lithuanians all working together, plus Americans on the exhibition side, which can make communication harder. You’ve got to be very careful that you really have been understood.

The cladding of the building presents a challenge too because that involves 40,000 anodised aluminium shingles. One of the sponsors of the project asked me recently what the most challenging project of my career has been and I told him ‘this one, of course!’

“A museum project always takes seven years because of all the angles to consider, from the sponsors to the people who are going to run the museum.”