Taking armed guards along on a day’s work for protection from pirates is not something most chartered surveyors have to factor into their plans.

But for Dr Simon Spooner MRICS, president of the Anglo-Danish Maritime Archaeological Team (ADMAT) and one of the world’s leading experts in maritime archaeology, it goes with the territory when working on shipwrecks in the Caribbean.

It’s in stark contrast to his full-time role as director of facilities, planning and sustainability at Algonquin College in Ottawa, Canada. Here, the facilities management department look after about 1.6m ft2 of campus and there is a decidedly smaller chance of unearthing buried treasures from a bygone era.

“Treasure hunters and looters are a major problem in the Caribbean,” says Spooner. “There are lots of culturally important shipwrecks that do have very valuable cargos, but not all. The pirates think they must all contain gold because they’ve seen it on the Discovery Channel.”

ADMAT is a non-profit organisation that assists governments with the protection of their underwater cultural heritage and teaches students maritime archaeology. While much of its work is very newsworthy, certain governments such as the Dominican Republic, aren’t keen on much publicity. That’s because a feature in the local news about a new dive site could act as a beacon to bad actors who are looking for wrecks to loot.

“If you’ve got a 15-person team, 30 air tanks, two boats, scientific geophysical equipment and a marine with a rifle, word gets around very quickly,” says Spooner. “A lot of the time the local fishermen already know where these wrecks are, but because they’re buried they don’t know what is there.

“We conduct forensic archaeological surveys and it’s literally a race against time to get access to the information and protect all the artifacts. If they're not protected, the looters will take them and they'll be gone forever.”

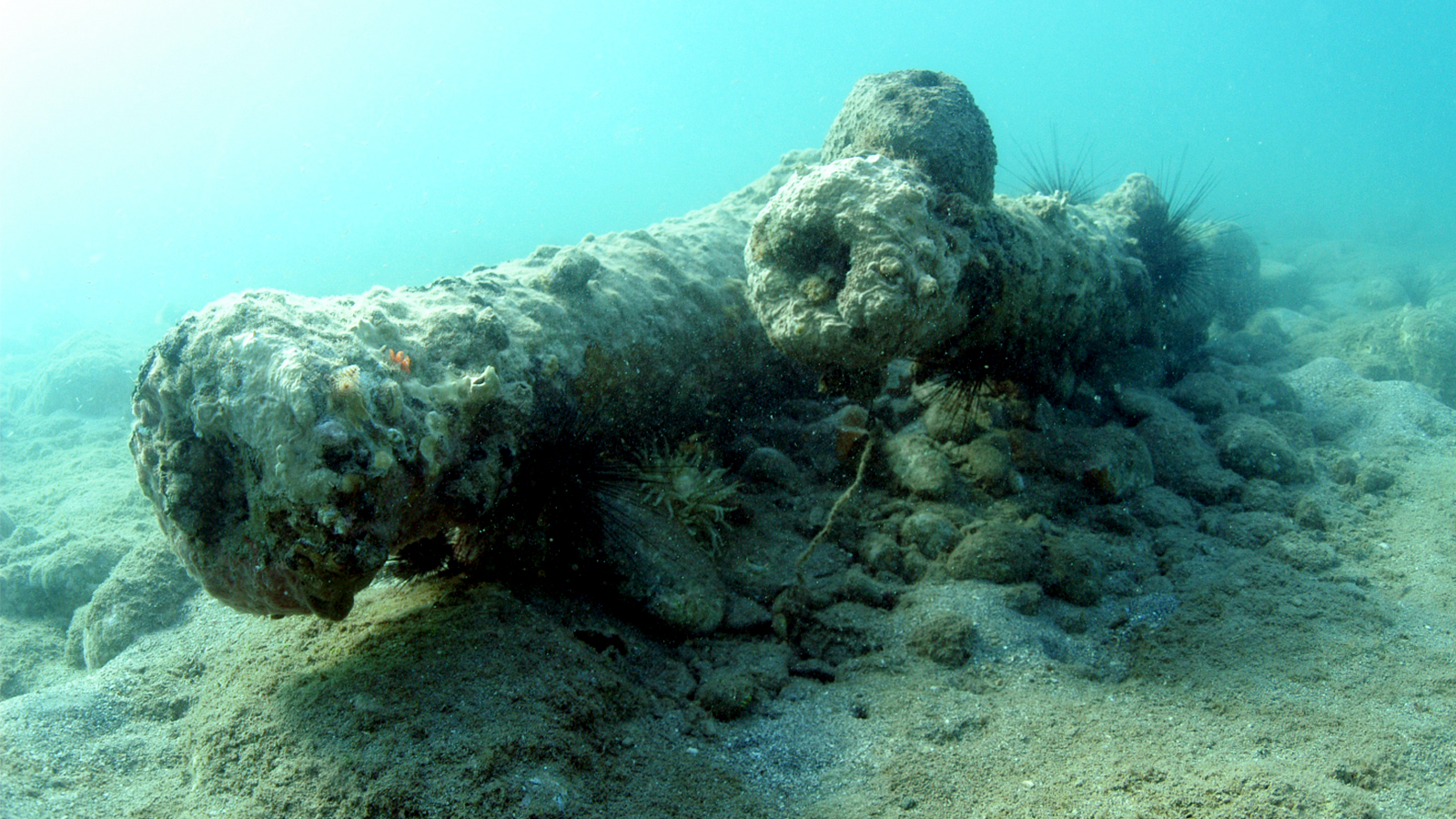

To illustrate his point, Spooner recalls ADMAT’s work on shipwreck called Le Casimir in the Dominican Republic. In 1998, a storm uncovered sections of the wreck site. Spooner conducted an initial survey on the site in 1998-99, when lead crystal perfume bottles and silver coins were discovered in tunnels in the reef. After they had gone, looters descended and destroyed large sections of the ship, using dynamite to blow up the reef as they believed there was more silver to be found. When ADMAT returned to the site in 2000 and 2005 for a full maritime archaeological survey, looters had been back and destroyed even more.

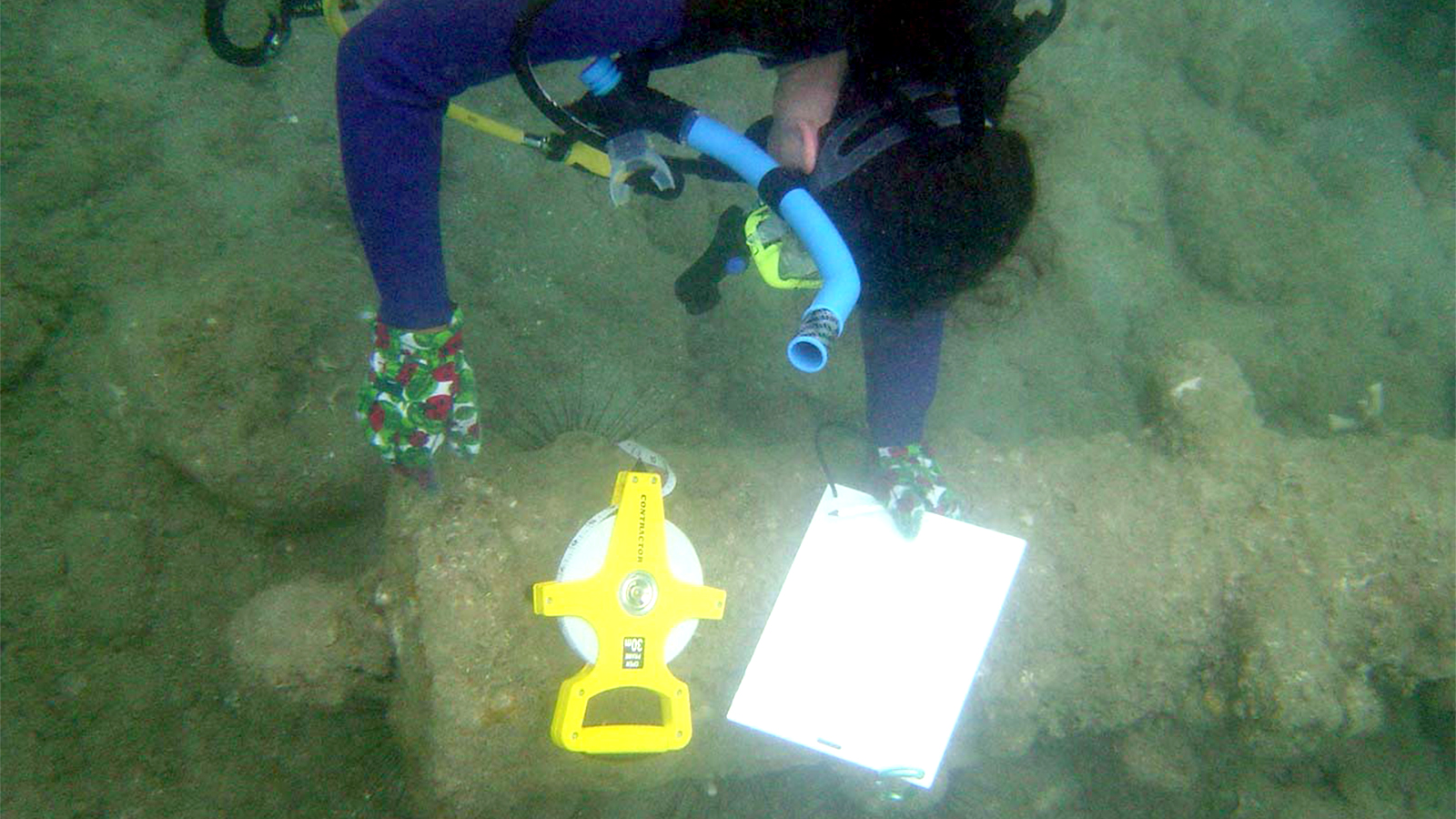

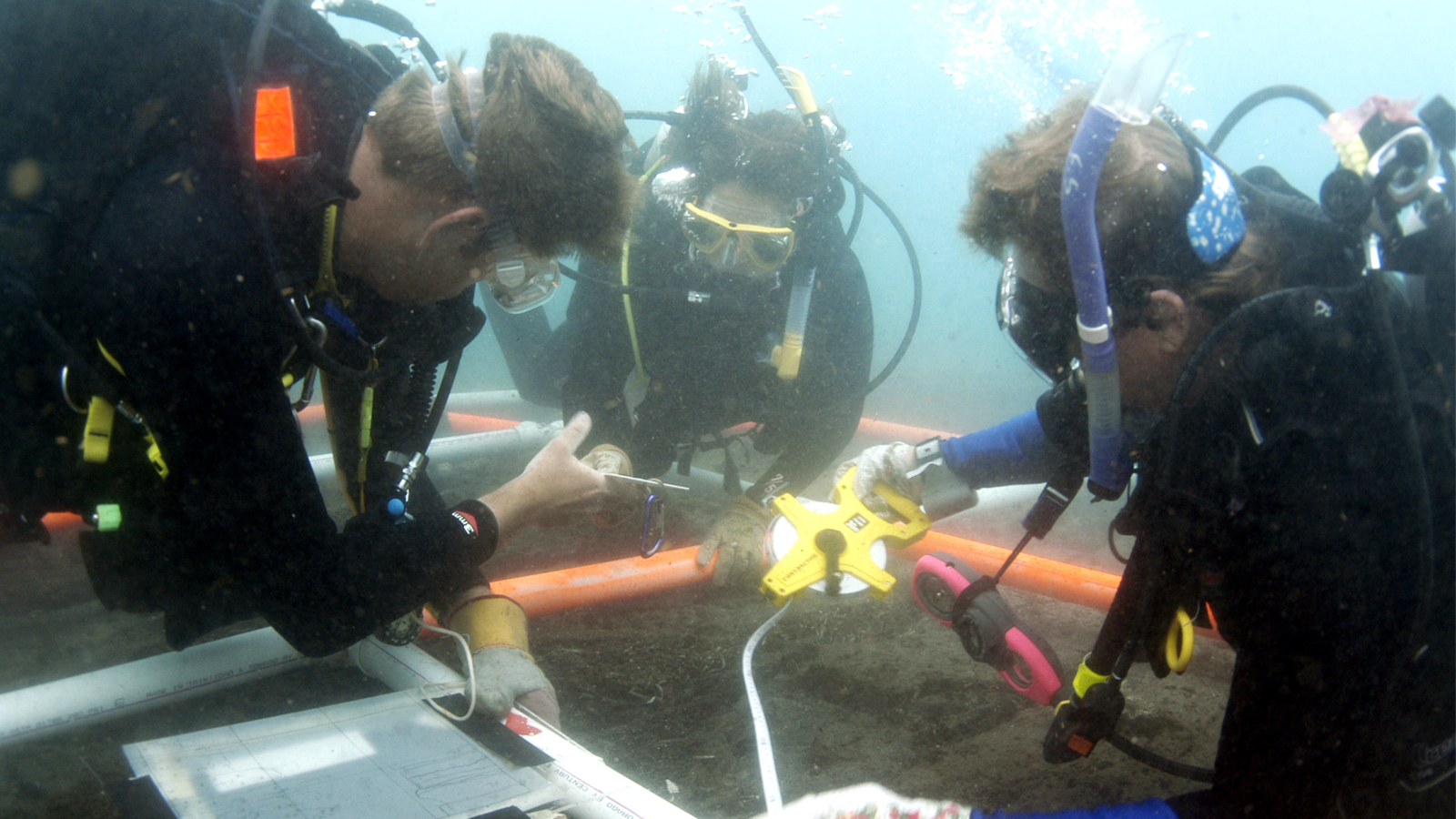

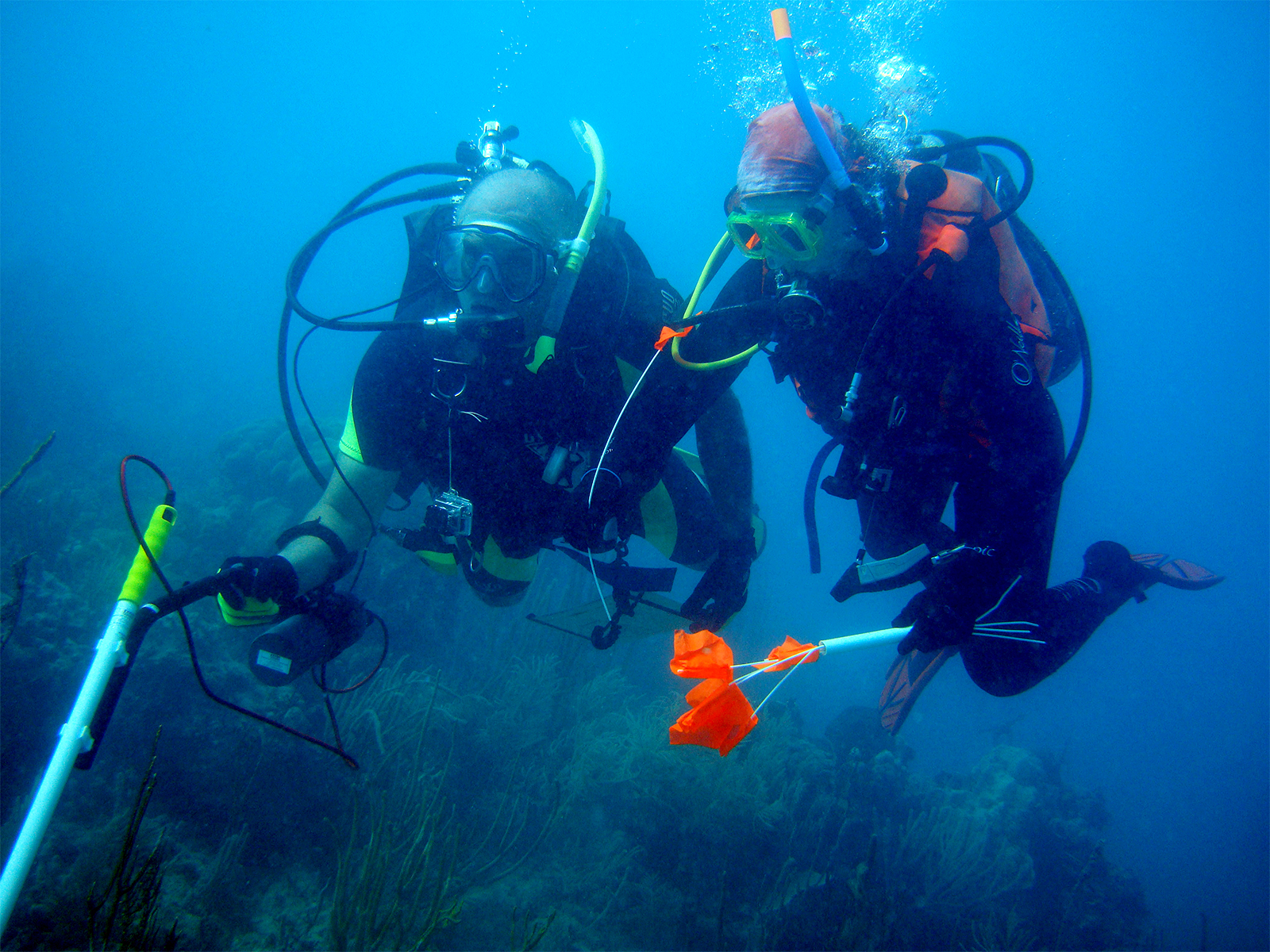

ADMAT surveying Le Casimir, sunk 27 April 1829, in the Dominican Republic. Finds included lead crystal perfume bottles

Under the sea

Surveying underwater requires a specialist skillset, but in many respects follows the same principles as working on dry land. Some elements are more manual because you can’t use most modern digital equipment underwater. A laser range finder won’t work because of all the particles in the water that will reflect the laser light back. GPS does not work underwater and if you are used to making efficient notes on an iPad-style tablet, think again.

“We use an underwater slate, made from plastic, and write with a pencil,” says Spooner. “Or Tyvek waterproof paper and a good old clipboard. We go through a lot of slates.”

Because ADMAT is usually working on Caribbean wrecks at relatively shallow depths of less than 10m deep in waters that are calm and warm, you don’t need to be a highly advanced diver. Spooner says the team, most of which are international student volunteers, usually have around 20 dives under their belt.

That said, it is still hard physical work and can involve spending five hours a day underwater. “Someone said to me once that maritime archaeology is like trying to measure things blindfolded while standing up in a hammock,” Spooner says. He also recalls being chased off one wreck by a swarm of highly poisonous lionfish.

The location of the dive sites has two main benefits for ADMAT. One is historical – the Caribbean is full of maritime heritage. “We realised early on that the Caribbean nations had thousands of historic shipwrecks as a result of the old European colonial empires, but they had no money or expertise to protect what is essentially another nation’s history,” says Spooner.

The other is that the sun-kissed location and favourable diving conditions attract students to volunteer their time with ADMAT. Without students working for the experience, ADMAT simply wouldn’t have the team needed to carry out the surveying and excavating work.

“I’ve done a fair number of lectures on cruise ships and one of them is entitled ‘History, Mystery and Baywatch’. If it's nice and sunny, you're going to attract people,” says Spooner. “If it's in the Arctic, you're not going to attract anybody. And the diving equipment needed for those type of environments is completely different, as well as the qualifications needed.”

“Maritime archaeology is like trying to measure things blindfolded while standing up in a hammock” Simon Spooner MRICS, Anglo-Danish Maritime Archaeological Team

“I felt the shipwrecks should be measured and recorded, and a chartered surveyor is one of the best people to do that” Simon Spooner MRICS, Anglo-Danish Maritime Archaeological Team

The origins of ADMAT

So how does a chartered surveyor go from the more traditional world of bricks and mortar to documenting 250-year-old shipwrecks in the Dominican Republic?

“Ironically, I couldn’t swim until I was about 14, I was frightened of the water,” says Spooner. “While I was at Kingston University doing my BSc in Estate Management, there was a scuba diving club where I learned to dive and became an instructor.” He also cites the vintage TV series The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau as a big influence in what would one day become his passion project.

With a father who had been a chartered surveyor and became the senior owning partner of Jones Laing Wootton (now JLL), Spooner says he “learned rent reviews at the age of six” and his career choice appeared obvious. “My first job was at Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, learning about local authority and running property portfolios. From there I went to Hillier Parker, where I ended up in the City, doing High Court arbitrations.” Over the past decade he has worked for Network Rail and DEFRA (the department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs), on a project protecting London from flooding.”

“I went down an archaeological route because protecting underwater cultural heritage was something that interested me. I felt the shipwrecks should be measured and recorded, and a chartered surveyor is one of the best people to do that. I set up ADMAT and at the same time was doing property work.”

ADMAT’s first project was in St Kitts, advising the government on the White House Bay Wreck. That ship had been involved in the Battle of Frigate Bay and the project went so well it was mentioned in the UK House of Commons at the time. It got a lot of good publicity for St Kitts and led to further projects in the Caribbean for the last 25 years, as well as the Button Wreck in Florida Keys, for the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

UNESCO estimates there are about three million undiscovered shipwrecks on the ocean floor, which means ADMAT is never going to be short of dive sites for the month or so a year that it operates. However, as a non-profit organisation, it’s not what you’d call a side-hustle – “I basically give up half my pay to keep it going, as funding is very hard to get,” says Spooner.

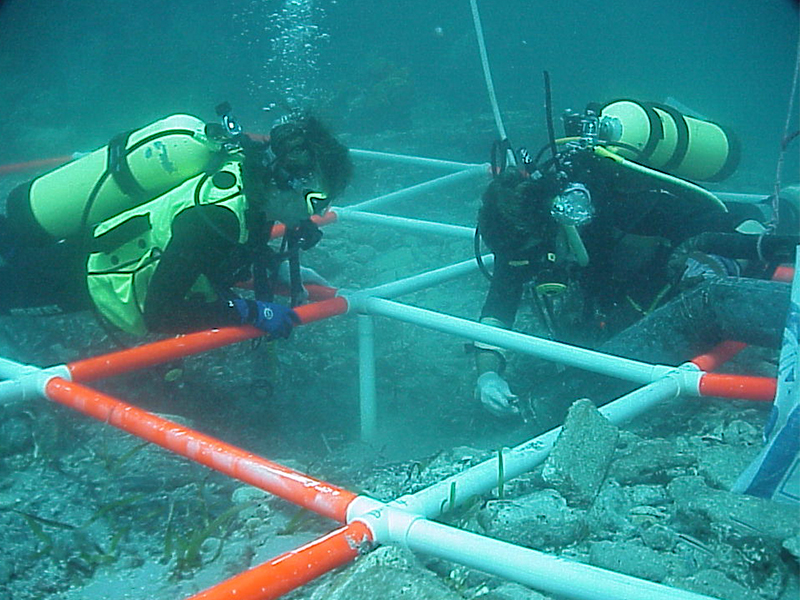

The maritime archaeological survey of Le Dragon on the north coast of the Dominican Republic. Video (right) is Simon working on the French Faience Wreck, built in the 1760s.

Diving into history

Most of the wrecks ADMAT works on are 200 to 300-years-old, with the oldest being the Tile Wreck, built around 1680. Unlike modern ships, when the construction is all documented, these ships do not have neatly archived plans that can help identify their constituent sections, cabins or equipment.

Spooner sees each dive as akin to travelling through time. “You're jumping from the surface in your 21st century armour, so to speak, which is your diving equipment and your wetsuit. Seven feet later you're touching the 17th century and their technology.”

“We forensically examine these shipwrecks over many years and then we go into the archives and we find their story, by piecing together all the little clues. It's like doing a 70,000-piece jigsaw puzzle without the picture on the box.”

And while they are wary of meeting modern-day pirates, there are fewer encounters with pirate ships from the Golden Age of Piracy (1650 – 1730) than you might think. Yet they regularly see traces of those infamous pirates in what they find.

“Monte Cristi, on the north coast of the Dominican Republic, is not too far from the island of Tortuga, which was the setting for parts of the film franchise Pirates of the Caribbean. On the Tile Wreck, we found 36 live grenades and loaded cannons which they must have armed because they thought they were going into hostile [pirate-inhabited] waters.”

You’d be forgiven for thinking boxes of grenades would perish in a ship that sank no later than 1723. But the reason the wrecks and much of their cargo survive for so long is because they are buried in the sand and kept out of sight as the decades pass by. “Anything that's buried in in the sand in the Caribbean will survive because it shuts off all the oxygen,” says Spooner. “The Tile Wreck also had alluvial mud from the mangroves on top of it.”

Which only adds to make the task of surveying shipwrecks more challenging. “A maritime archaeologist not only has to be a good surveyor, they have to know ship construction, be a good diver and understand logistics because you've got to make whole projects happen,” says Spooner.

Despite the exciting nature of the work, it’s still a very niche branch of surveying with few paid positions at commercial companies available, Spooner says. “I once told a conference at which I was speaking that there are more astronauts than there are experienced maritime archaeologists.”