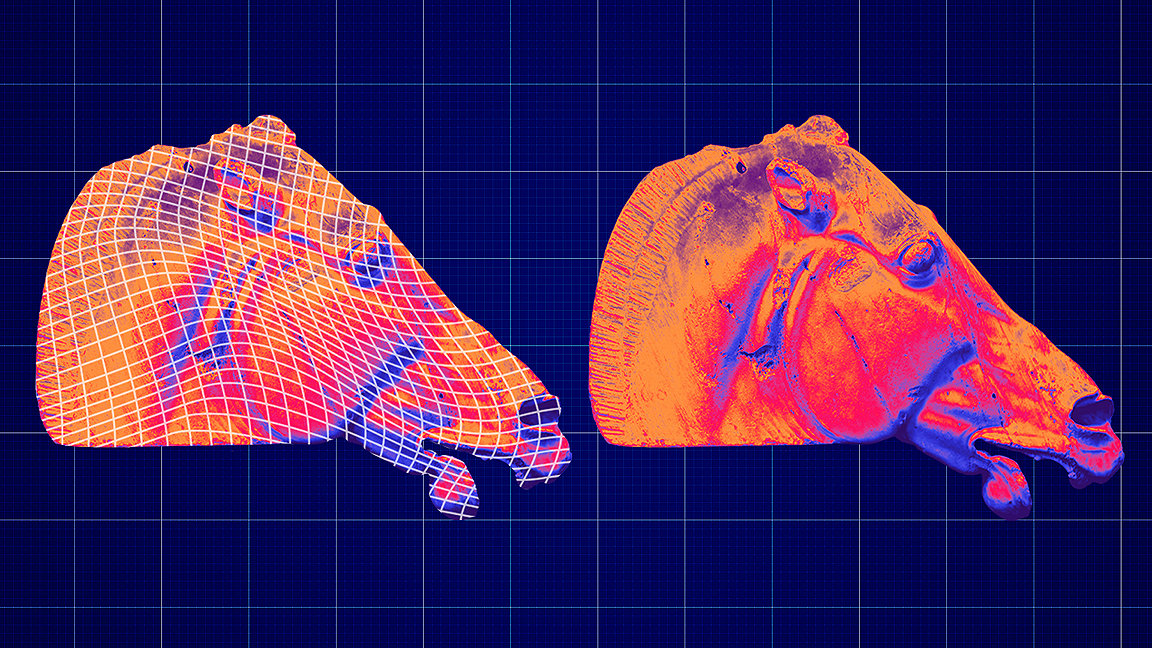

Horse of Selene

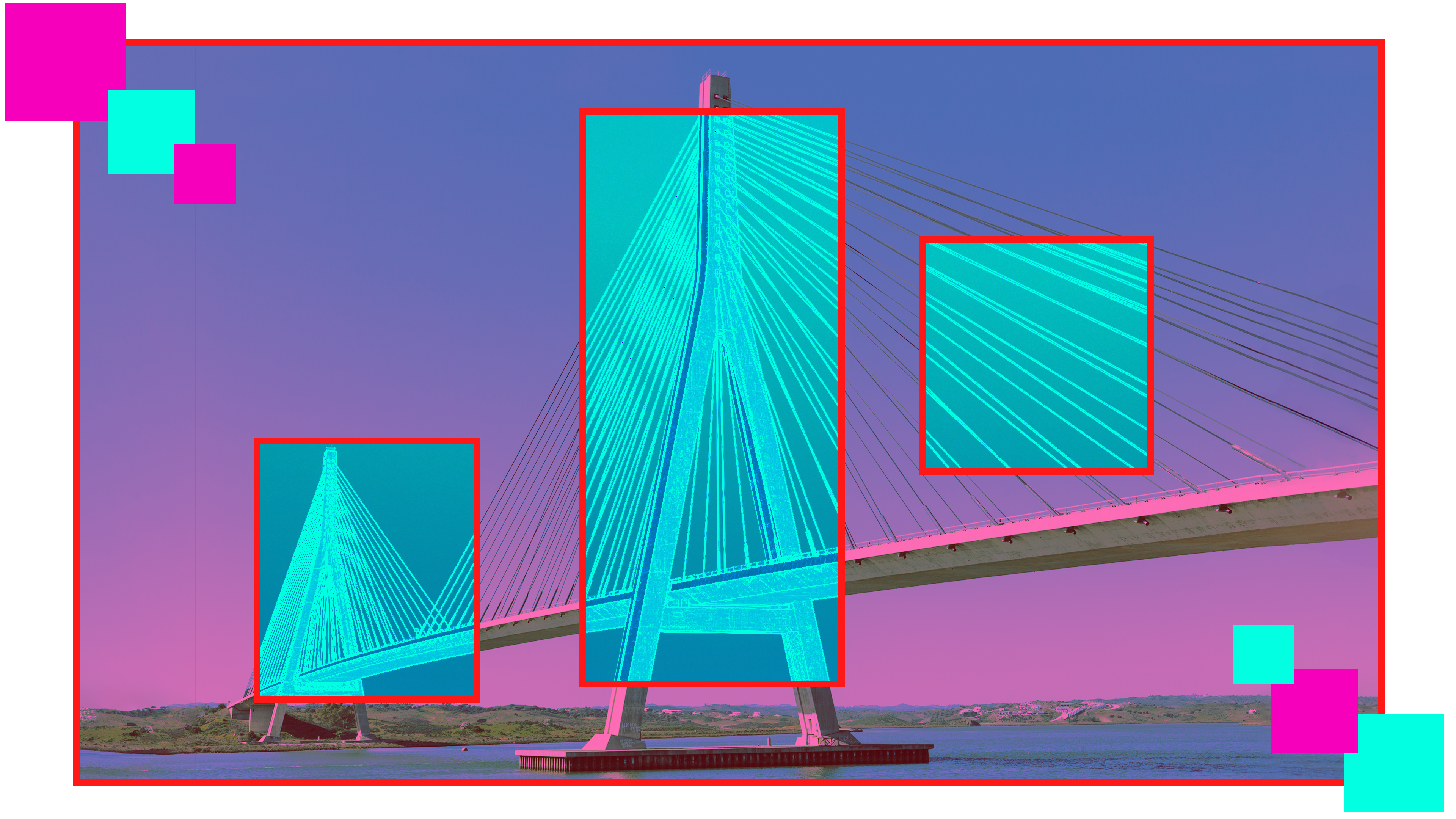

Archaeologists are normally associated with patient research and site investigation, not covert operations. But one day in March 2022, two experts from the Institute of Digital Archaeology (IDA) paid a visit the British Museum to ‘capture’ one of its most precious exhibits.

The pair entered the Duveen Gallery as visitors and, working “entirely within visitor guidelines,” used an iPhone, iPad and camera to scan detailed 3D images of the Horse of Selene – an ancient sculpture of a horse’s head from the Parthenon in Athens, the Greek temple famed for its incredible marble sculptures. They did nothing illegal, despite a more formal request made to the museum being refused, although it’s arguable that there was an element of stealth involved.

The data was subsequently enhanced to full millimetre resolution by technology partner AccuCities, then uploaded to a six-axis robot at a workshop in Carrara, Italy, which carved a copy of the sculpture made from the same Pentelic marble.

As you might have guessed, this was no heist, but an attempt to resolve an ongoing dispute between the UK and Greece over ownership of the so-called Elgin Marbles. The priceless collection of sculptures and bas-reliefs were taken from Greek temples on the Acropolis site by agents of Thomas Bruce, the seventh earl of Elgin, between 1801 and 1812.

The IDA hoped its ‘like-for-like’ copy of the horse, and potentially other pieces, would be put on display by the British Museum instead of the originals, enabling them to be returned to Athens.

Technology is changing the conversation

Although debate over where they should reside continues, the IDA’s work highlights how far 3D survey techniques, including LiDAR (light detection and ranging) laser scans and photogrammetry, have come in recent years, revolutionising how ancient monuments and artefacts are studied and preserved.

Innovative smartphone apps have democratised the act of surveying, allowing almost anyone to document, with relatively high accuracy, treasured objects and details that may be destroyed as result of war, natural disasters or climate change. The rise of AI is enhancing the analysis of 3D survey data, making it possible to spot hidden relics underground.

Dr Alexy Karenowska, director of technology at the IDA, who managed the Horse of Selene project, claims we have reached a stage where survey technology capabilities are “no longer the limiting factor” when it comes to meeting project demands.

“What you can access is just incredible,” she says. “Hollywood would have given its right arm for this kind of thing 20 years ago …The really exciting part now is what you do with the data once you've got it.”

Fake or fortune?

In a world where our professional and private lives are increasingly populated by virtual digital experiences – VR and mixed reality are becoming part of everyday technology – the IDA project raises questions about ideas of authenticity and reproduction.

The horse’s head has the same “touch, feel and density of the original,” says Karenowska, because it is made of the same marble, lending credibility to the copy. The ability to produce high quality replicas for museums at the push of a button opens the door to a situation where, “rather than have to slice up the cake,” you can simply “bake another one,” and historic objects can be distributed anywhere and experienced by almost anyone.

The potential to transform our understanding of history and enrich educational experiences is inspiring, says Angeliki Ntourou MRICS, art and antiques surveyor at Art Valuation: “High quality 3D replicas of ancient or historic monuments, especially designed for museum purposes, can bring culture closer to the public, providing educational experience with interactive displays. Museum visitors can touch and feel the unparalleled excellence of past artistry, while online visitors can also view detailed, photorealistic 3D representations of mankind’s greatest monuments.”

Culture capture

Warfare can swiftly erase cultural heritage and with it a country’s identity, but digital scans are helping preserve artefacts and buildings and the 3D models can be stored in archives safe from the threat of bombs and bullets.

The ground-breaking initiative Backup Ukraine, led by the Danish UNESCO National Commission, Blue Shield and 3D start-up Polycam, was set up in response to the damage caused by war in Ukraine.

The project has turned ordinary Ukrainians with smartphones into amateur surveyors, able to capture buildings and monuments as full 3D models with Polycam’s app. Machine learning algorithms convert this data, alongside data from LiDAR and location sensors, into high-definition museum-grade 3D digital blueprints, which are stored in an open, secure archive in the cloud. Tens of thousands of captures have been made to date and 3D printing technology used to create replicas of threatened statues.

A similar 3D printing approach was applied to an entire monument by the IDA when it created a life size replica of Syria’s 1,800-year-old Triumphal Arch of the Temple of Bel, after the original was destroyed by Islamic State militants in 2015. The replica arch was erected in Trafalgar Square in London.

It's not only wars that can destroy cultural heritage. Natural disasters, such as earthquakes and tsunamis, pollution and extreme weather brought on by climate change can damage or aggressively erode the surface of ancient buildings and monuments. Thankfully, 3D capture and/or 3D printing make it possible to document them before they disappear.

This can sometimes reveal features that would otherwise remain hidden, explains Angelos Sotiropoulos, an expert conservator and restorer at the German Archaeological Institute: “Ancient monuments often have hidden features that the human eye cannot trace. Detailed scans can reveal traces of ancient or historic graffiti (engravings), details about decoration, and deformations in the structure due to natural disasters.”

“High quality 3D replicas of ancient or historic monuments can bring culture closer to the public” Angeliki Ntourou MRICS, Art Valuation

Syria’s 1,800-year-old Triumphal Arch of the Temple of Bel replica in Trafalgar Square

"Analysing LiDAR data with AI can expose historical features, such as ancient earthworks, that are difficult to detect with the naked eye” Iris Kramer, ArchAI

Mission critical

California is home to several historic mission church buildings, built in the 1700s during Spanish occupation, most of which are in a fragile state of partial-ruin and exposed to earthquakes in an area known for seismic activity.

Survey specialists GB Geotechnics USA is involved in a project to laser scan the Mission San Juan Capistrano in Orange County, a Spanish Baroque-style church built in 1776 by Spanish Catholic missionaries. The firm is monitoring the building’s movement over time by comparing detailed models, combining 3D point clouds and photogrammetry, year-on-year.

“Advances in laser scanner technology mean that today you can carry out a massive, detailed survey in days,” says Chris Gray MRICS, associate reality capture at GB Geotechnics USA. He recalls a job in the 1980s, surveying the west front of York Minster in the UK after a fire, when “it took about two months to scaffold it, then six months to measure it.”

Capturing ancient buildings damaged by fire is a challenge for surveyors if there are safety concerns or if architectural details can’t be reached by conventional methods due to risk of collapse.

The risks were so great for architects and restorers surveying the massive fire-damaged monastery of Skete of Saint Andrew on the Athos Peninsula in northern Greece, they decided to turn to the use of drones to do the work.

The entire building complex, covering some 20,000m2 per floor over six storeys, plus multiple underground complexes, was captured by the firm Imantosis. Using a combination of aerial photogrammetry and 3D data from terrestrial laser scanners, they created a model with a precision of one millimetre for every construction detail.

“Advanced 3D reality capture creates a faithful digital twin of the historical subject, freezing time at the moment of data acquisition,” says Kampouris Apostolos, an architect and restorer engineer at Imantosis. “The 3D representation serves as a database where historical entities coexist and are available for simultaneous study and evaluation.”

The company was able to achieve the same level of detail capturing the entire archaeological site of the Temple of Zeus in Ancient Olympia, one of the largest archaeological sites in Greece, where the Olympic Games originated.

Signs of life

Apart from fire, historical sites are under constant threat from construction as inadequate or poorly executed field assessments leave buried archaeology exposed to potential damage and destruction by diggers, excavators and other heavy machinery.

UK-based tech start-up ArchAI aims to improve their protection by using AI to analyse LiDAR, satellite imagery and historic maps and automatically detect potentially historic sites where construction is due to begin.

Archaeological site assessments are required as part of environmental impact assessments when seeking planning permission in Europe. ArchAI’s AI models interrogate thousands of images and give rapid feedback to developers and project planners.

Temple of Zeus, Athens

“Advances in laser scanner technology mean that today you can carry out a massive, detailed survey in days” Chris Gray MRICS, GB Geotechnics USA

Mission San Juan Capistrano, California

Mission San Juan Capistrano, California

Skete of Saint Andrew, Athos. Photo by Саша Шљукић

A pilot case study on the Isle of Arran identified 200 new potential sites, of which more than 130 were verified as true sites by experts at Historic Environment Scotland.

Company founder and CEO Dr Iris Kramer was last year awarded a £50,000 grant by Innovate UK’s Women in Innovation programme to scale-up the business. Current clients include the UK’s Forestry Commission and the National Trust.

Kramer says: "Analysing LiDAR data with AI can expose historical features, such as ancient earthworks, that are difficult to detect with the naked eye. These insights are crucial for advancing our understanding of the historical landscape and filling in knowledge gaps about our heritage."

Deploying the technology in the early planning stages avoids “project delays, and reduces the risk of incurring additional costs," she adds. However, one limitation of LiDAR is its “inability to detect buried archaeology”, and although combining it with satellite imagery can improve detection, this “can increase project costs.”

Blending past and present

Survey hardware and software tech is constantly evolving or combining with systems already in use. Recent advances mean “areas too inaccessible, dangerous, or expensive to visit can be viewed from the safety of home,” says Sotiropoulos, who adds that it is now possible to “experience the past and present simultaneously,” by viewing the “historical 3D representation of a monument blended with its current dilapidated condition.”

Super accurate and high-fidelity datasets have been made possible through the combination of laser scanning, photogrammetry, the improvement of camera sensors and other methodologies. Andy Beardsley, an AssocRICS surveyor and managing director of geospatial surveying company Terra Measurement highlights how gaming algorithms have accelerated the way models can be viewed and interacted with, while zooming in can reveal detail almost at a granular level.

However, that doesn’t remove the need for humans in the mix to bind all the data together to produce accurate results. “Best practice survey methodology will never change,” says Beardsley. “Data must always be controlled, otherwise how can you know that something is as accurate as you claim?”

Beardsley says he frequently has to deal with data or surveys that have not been done properly because people that aren't surveyors have been convinced to buy the latest gear and use fast-track methodologies without having the necessary expertise or training.

So, what about the future? According to Yiannoulis Dimitrios, an architect and restorer engineer at Imantosis, cutting edge approaches include real-time scanning using systems like SLAM (Simultaneous Localisation and Mapping) and “special vision glasses” that photograph from the perspective of the wearer and use the data to generate 3D models, although “this still needs improvement,” he says.

Just as the ancient Greeks could never have predicted that one day an autonomous robot would be able to carve a near-perfect copy of one of their fabled sculptures, who knows where new surveying developments will take us and what marvels will be possible in centuries or millennia to come.