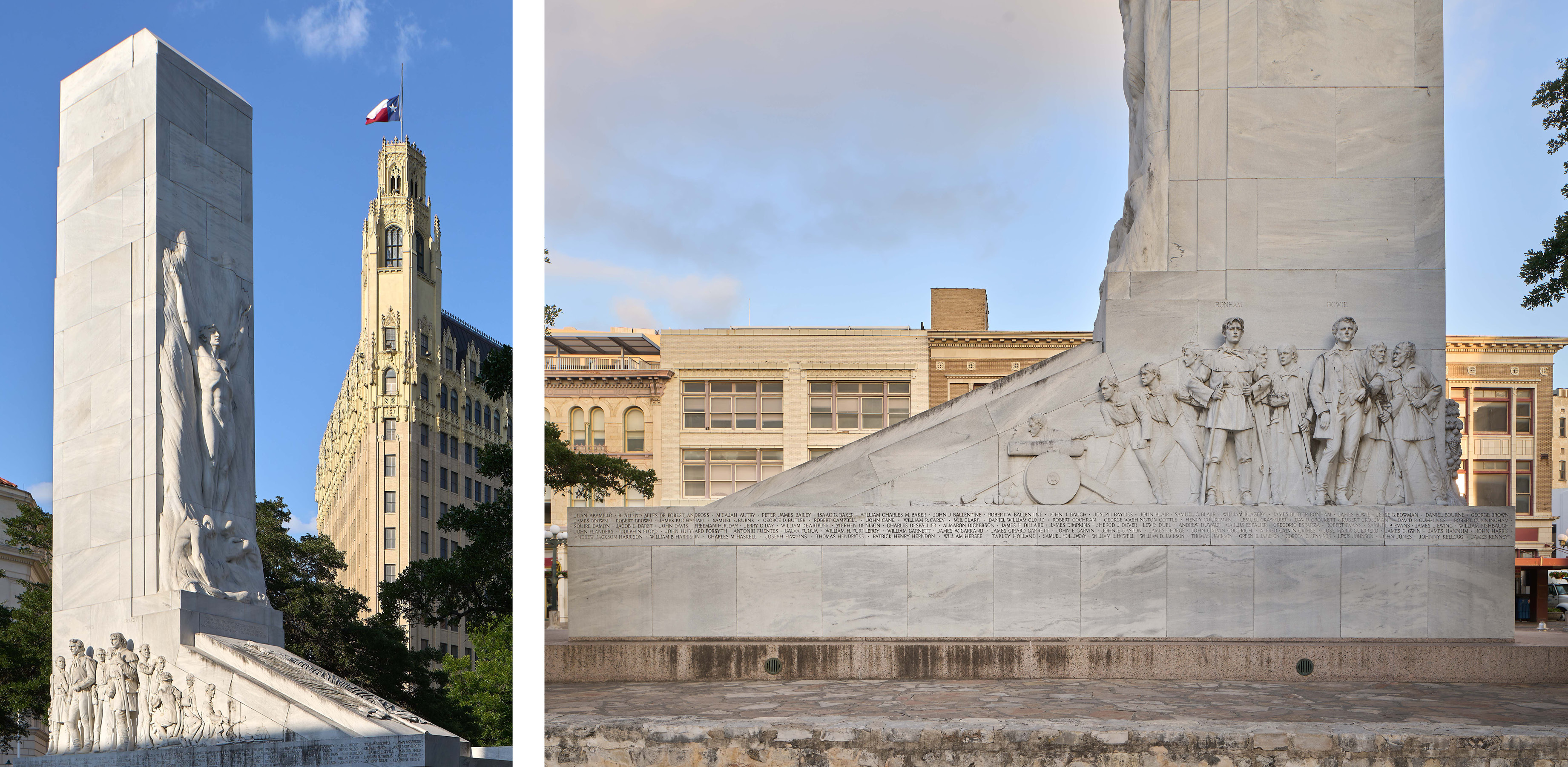

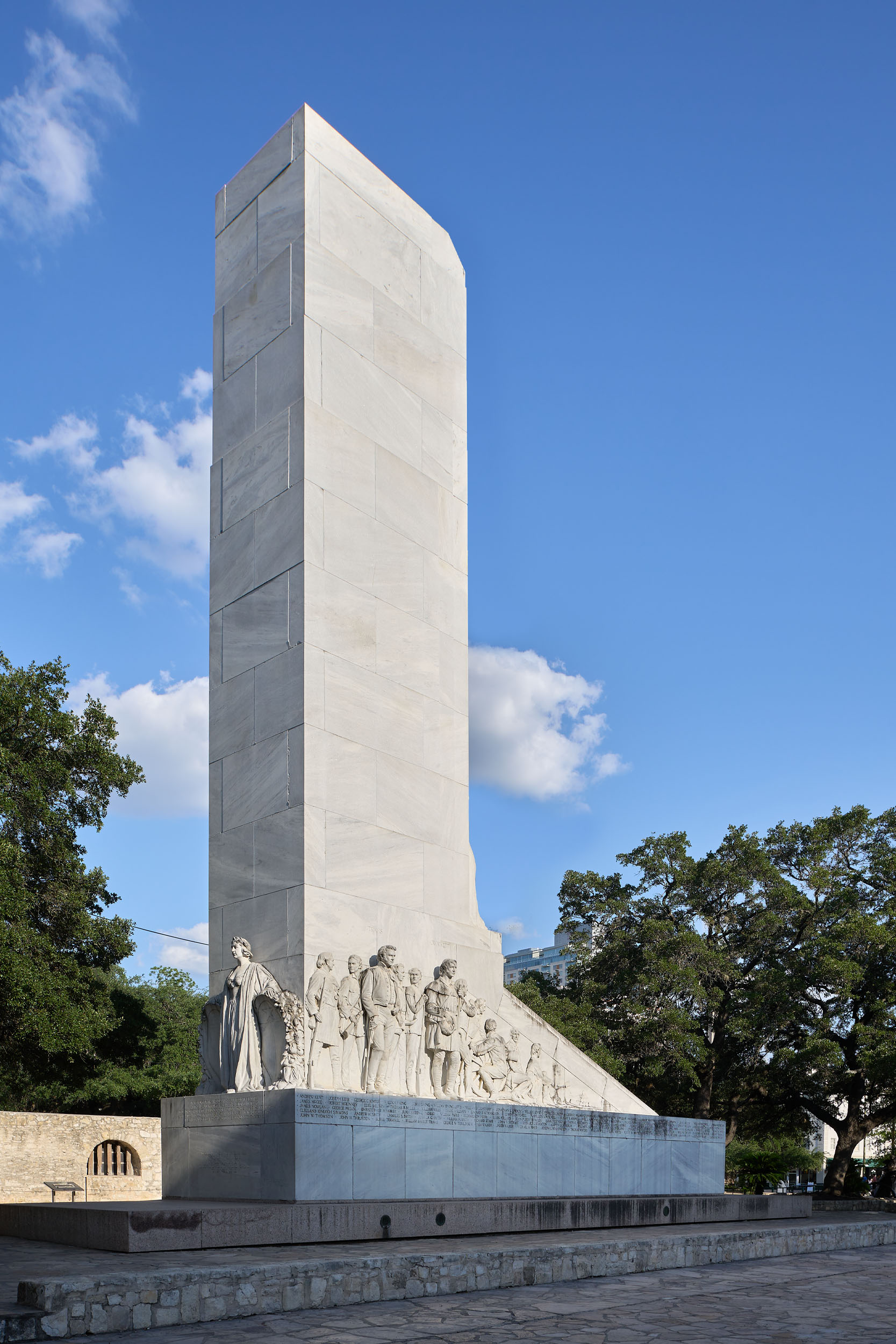

Photography by Dror Baldinger

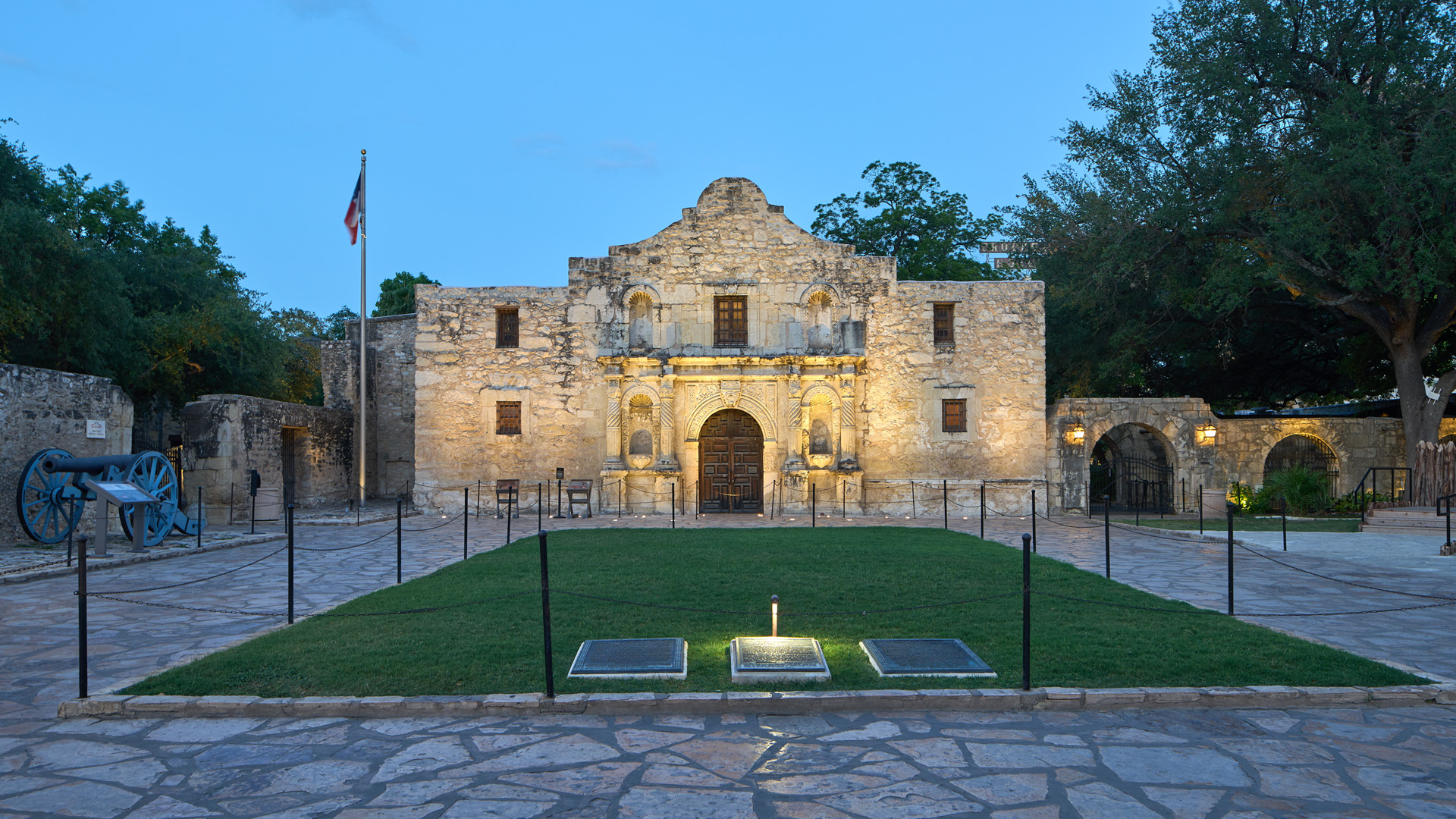

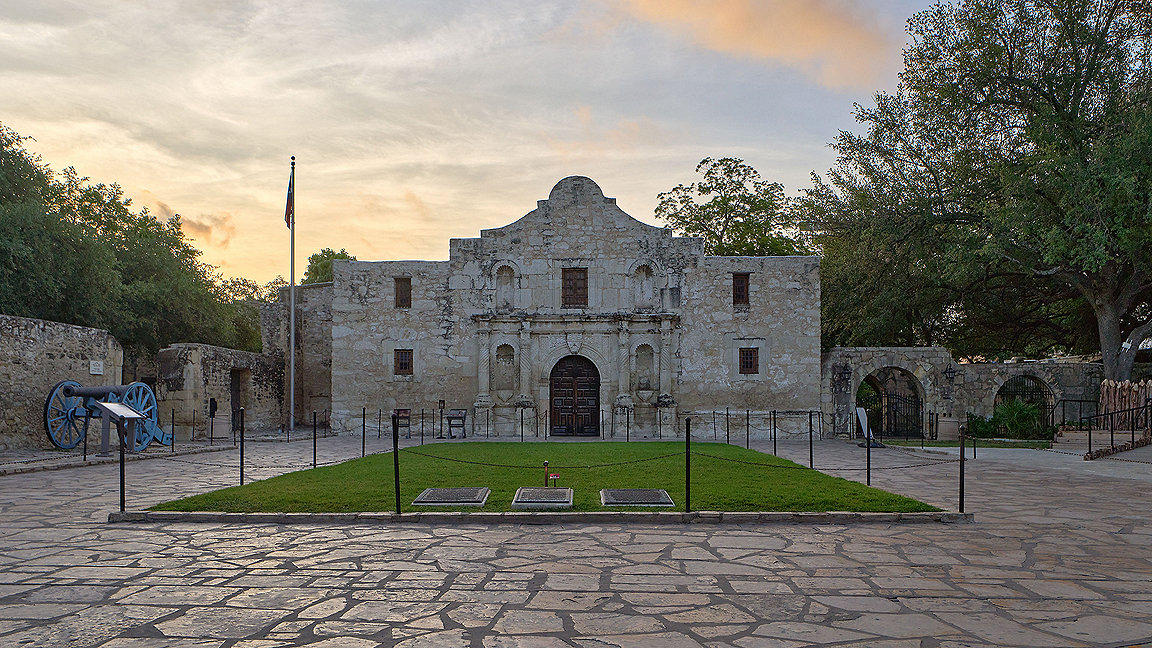

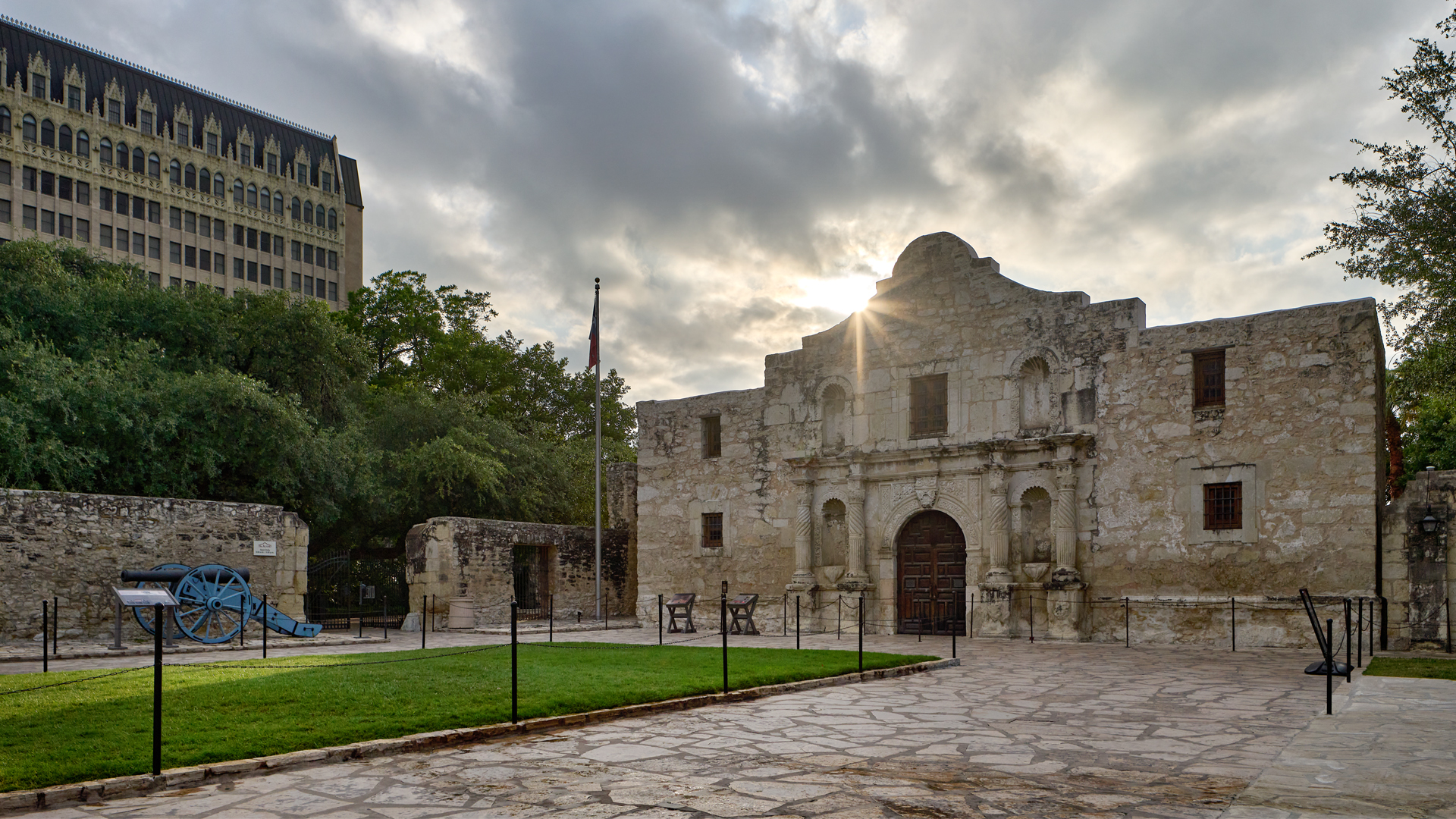

The Alamo is an important historic location in the US and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in San Antonio, southern Texas. It began life as Misión San Antonio de Valero in 1718, established by Spanish catholic missionary Antonio de Olivares.

In 1836, it was the site of a famous battle between the forces of Mexico (for whom General Antonio López de Santa Anna led an army of several thousand) and a small defending Texan army of no more than 260 men, holed up behind the Alamo’s walls. It went down in history as the place where American folk heroes James Bowie, William Travis and Davy Crockett died defending the Alamo and the liberty of Texas.

The events of the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution have been the subject of many movies over the years, from Martyrs of the Alamo in 1915, to, most recently, The Alamo in 2004. These days, the site has become a place of pilgrimage for many Texans and Americans, and it receives 2.5m visitors a year.

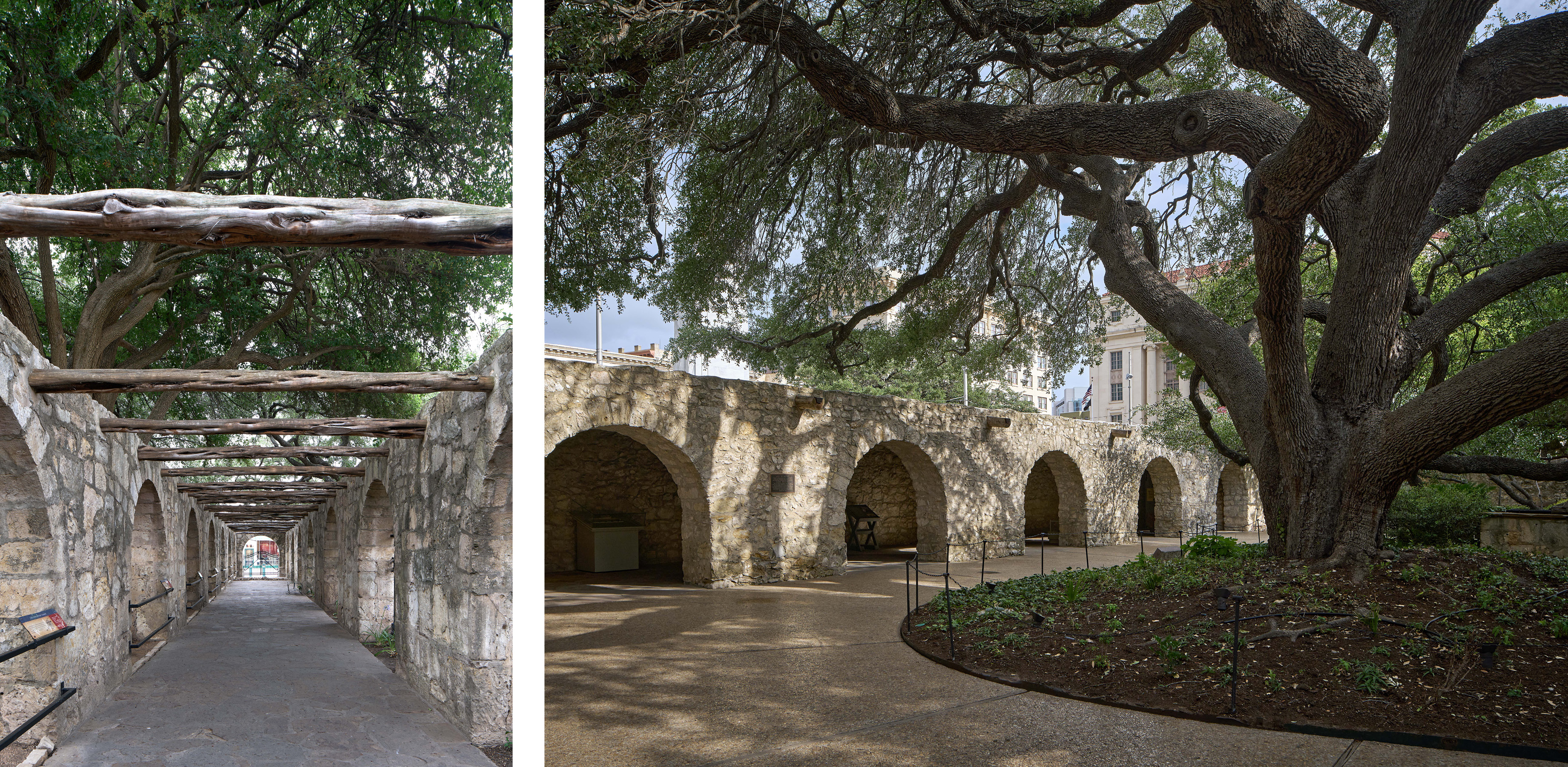

The person in charge of preserving this historic site of national interest is conservator Pam Rosser, who has been looking after the Alamo, including its chapel and Long Barrack (where photography inside is not permitted), as well as the Cenotaph for 12 years. She says there are plenty of challenges and nothing happens quickly when undertaking repairs, for very good reason.

“There have been lots of past preservation projects that have not worked,” says Rosser. “What we do now is extensive monitoring, testing and analysis below grade and above grade to help us determine what the next steps are. We don’t rush into any preservation decisions without doing the proper assessments.”

When repairing something as old and fragile as the Alamo, it’s a very different affair to repairing a modern building. If you spot something that needs repairing, you can’t just go to the DIY store to get the materials to fix it. For a 300-year-old limestone structure like this you monitor, test, wait for the test results and if they are inconclusive, you test some more. “We need enough data to make the right decisions,” says Rosser. “It’s human nature to think ‘we’re ready, let’s fix this now’. But the Alamo isn’t an easy fix, it’s going to take some time.”

“The limestone at the Alamo church has a lot of gypsum and clay and we need to make sure the new limestone put there has similar properties” says Rosser. “Texas has a lot of limestone but you need to make sure that different limestone from different quarries has the same properties, because some may have lower levels of clay content. Everything needs to be as closely matched as possible, so it all gets along.”

“I look at the stones as like humans. They’re going to be sitting next to each other for a really long time with mortar in between so they’ve got to be balanced and blend well.”

“We don’t rush into any preservation decisions without doing the proper assessments” Pam Rosser, Alamo Trust

A very sick patient

Rosser says her team at the Alamo are currently doing a moisture monitoring programme, collecting data to create a report that will inform their next moves. This process includes lots of sensors in the walls that collect information on temperature, humidity moisture movement and whether there’s water flowing under the building. By doing this they can detect why the walls are deteriorating so rapidly.

“I refer to the Alamo as a very sick patient,” says Rosser. “If you walked through the church now you would see sensors inserted into the walls and it’s like seeing someone in the hospital hooked up to lots of monitors. That’s what the Alamo is right now, but that’s what’s best for it.”

A sick patient it may be, but it’s also a popular patient that receives millions of visitors each year. This presents a challenge in the preservation of a notable historic site, says Warren Adams MRICS, historical resources and cultural arts director at City of Coral Gables in Florida.

“Increased visitor numbers do provide a valuable source of revenue; however, this also leads to a number of challenges,” says Adams. “Firstly, with more visitors, comes additional wear and tear of the building fabric which leads to increased maintenance costs. Other factors to consider are visitor management, security, accessibility, insurance, and staffing.

“As well as increasing costs, some of these factors result in design challenges such as the installation of signage and alterations to meet access requirements. As visitor numbers continue to grow, a decision may be taken to provide dedicated parking or, in some cases, a new visitor centre.”

“Increased visitor numbers do provide a valuable source of revenue; however, this also leads to a number of challenges” Warren Adams MRICS, City of Coral Gables

One recent change that’s made a big improvement to the Alamo site for visitors is closing off some of the roads surrounding it to vehicles. “It’s been wonderful, visitors are roaming around, up and down the closed South Alamo Street and they don’t have to worry about cars and buses,” says Rosser. “It’s really changed the feel of the plaza as you come up to the Alamo and no longer feel like you’re on a major thoroughfare.

“It was our way of taking back what is needed to create a place of reverence, with more of a plaza feel, more of a World Heritage Site. You can’t have that if you have a street running right through the plaza.”

Being surrounded by a busy city isn’t a problem that all UNESCO sites have to deal with, but bustling San Antonio has grown up around the Alamo. This could be a contributing factor to the deteriorating condition of the historic site, so taking car traffic and vehicle exhaust fumes out of the equation can only be a good thing for the building and its visitors.

“It’s human nature to think ‘we’re ready, let’s fix this now’. But the Alamo isn’t an easy fix, it’s going to take some time” Pam Rosser, Alamo Trust

Doting daughters

Long before car traffic was a problem, in the late 1800s, an organisation called the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT), began looking after a neglected Alamo site that was falling into disrepair. The DRT was founded by women who have descendants that settled in Texas before February 1846, when Texas ceased to be an independent republic.

In the early 1900s the daughters purchased the Alamo property from the state of Texas and then gave it back on the condition that they would be the custodians and take care of the Alamo. They continued to be the custodians until the Alamo gained UNESCO membership in 2015.

It was during their custodianship in 2000 that Rosser, a member of the DRT, made an important discovery in the church’s sacristy that had been hidden during the building’s time as a military post.

“When the US Army came in, they did not want the Misión San Antonio de Valero to look like a mission, they wanted to make it look more military, so they made a lot of changes. And one of them was painting the walls white.

“My mom and I scraped away around 10 layers of US Army whitewash under magnification and exposed four mission-era fresco designs.

Striking a balance

The two main challenges for significant historic sites, says Adams, are “obtaining funding for the ongoing interpretation and maintenance of the site and the availability of experienced professionals to identify issues and undertake repairs and alterations in an appropriate manner.

“Additional challenges include development pressure and protection of a site's setting and achieving a balance between increased heritage tourism and the protection of the site.”

“There are many reasons historic sites suffer from dilapidation and neglect, including a lack of funding, the cost of restoration, deliberate neglect in an attempt to demolish the structure and redevelop the site, as well as a lack of professionals trained in this field.”

Fortunately, the Alamo is in good hands with Rosser and her team, as they continue to look after this 300-year-old symbol of Texan independence and ensure millions more visitors can pay their respects in years to come.