Over the past decade, drones have become a standard tool for many land surveyors. Now, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly used to gather data, enable communication and increase efficiency on construction sites.

“In the US, the majority of large construction projects will have a drone involved at some stage,” says Mike Winn, chief executive of San Francisco-headquartered tech firm DroneDeploy. “The market has grown very rapidly and will continue to grow. That’s because the tools have become simpler and more accurate, so we are seeing them integrated into the workflow on construction sites from beginning to end.”

Drone technology, both hardware and software, is advancing rapidly. Drones can be fitted with a wider range of equipment, such as thermal imaging and lidar (light detection and ranging) sensors, supplementing the use of conventional cameras. Meanwhile, cloud-based applications allow built environment professionals to access and analyse a wide range of data without the need to buy their own specialist drone-related software.

Contractors’ use of drones can start as early as the bid process, says Winn. “They can use drone data to better understand the state of the site and what earthworks will be needed, so that they can bid more precisely, and win more contracts.”

But it is once building work has begun that drones really come into their own, as a tool for overseeing on-site activity. “Most of the big main contractors have their own their own drones for monitoring progress,” says Michael Hannaway FRICS, managing director at Landsurvey Group in Northern Ireland. “If you have a tablet and a pre-programmed mission plan for the drone, you can run that mission over again weekly, or bi-weekly to get very accurate records of how the work is progressing.”

Saving surveyors’ time

Drones, and the data that they gather, promote improved communication and collaboration, says Peter Kinghan MRICS, a mineral and geomatics surveyor at Quarry Consulting in Ireland. “Getting better and more frequent data and integrating it into work streams enables better management of the site. This means significant savings in time, as well as a safer environment. Within 30 minutes of doing the drone survey, the information can be with the architect or client, instead of having to physically inspect the site and produce a report.”

Using drones, an up-to-date and accurate picture of the activity on a large and complex site can be relayed to an executive without them having to leave their office, says Daniel Lam MRICS, Hong Kong-based associate director at project management consultancy Blue Stone Management. “It is the data that you need, and drones are the facilitator for the data.”

He outlines several use cases for drones in construction: showing workers a drone fly-through of the site for more impactful safety briefings; using heat-sensitive cameras to reveal cracks, water damage, and concrete spalling, then using artificial intelligence to analyse the data and predict the likely location of further flaws; and approving payments to subcontractors by comparing the as-built data from the drone scan with the BIM design model to certify which tasks have been completed.

Drone data can be combined with 360-degree internal lidar scanning carried out by robots to produce a full 3D digital twin of the project, and then observe how it progresses over time, Winn explains. “Instead of travelling to the site, people can go and visit the virtual environment, they can measure it, they can see the change over time, they have a full audit trail of exactly what happened when, so if there's a dispute, they have the data to resolve it. Then the next step is using machine learning to extract the attributes of that environment and generate insights.”

“Within 30 minutes of doing the drone survey, the information can be with the architect or client” Peter Kinghan MRICS, Quarry Consulting

Drones are improving

While technology has improved, drones still have their limitations. Battery life is one such, says Lam. With drones typically only able to stay airborne for 20 to 25 minutes, prolonged site monitoring missions may require the use of a ‘tether’ – essentially a lengthy extension cord. Civil aviation regulations, aimed at reducing the risk of collisions with manned aircraft or preventing faulty drones falling from the sky and injuring unsuspecting civilians, can also prove a hindrance. Especially in dense urban environments such as Hong Kong. “At the moment, you need to apply for a permit for every use case of one of the heavier drone types, which is a huge challenge,” he says.

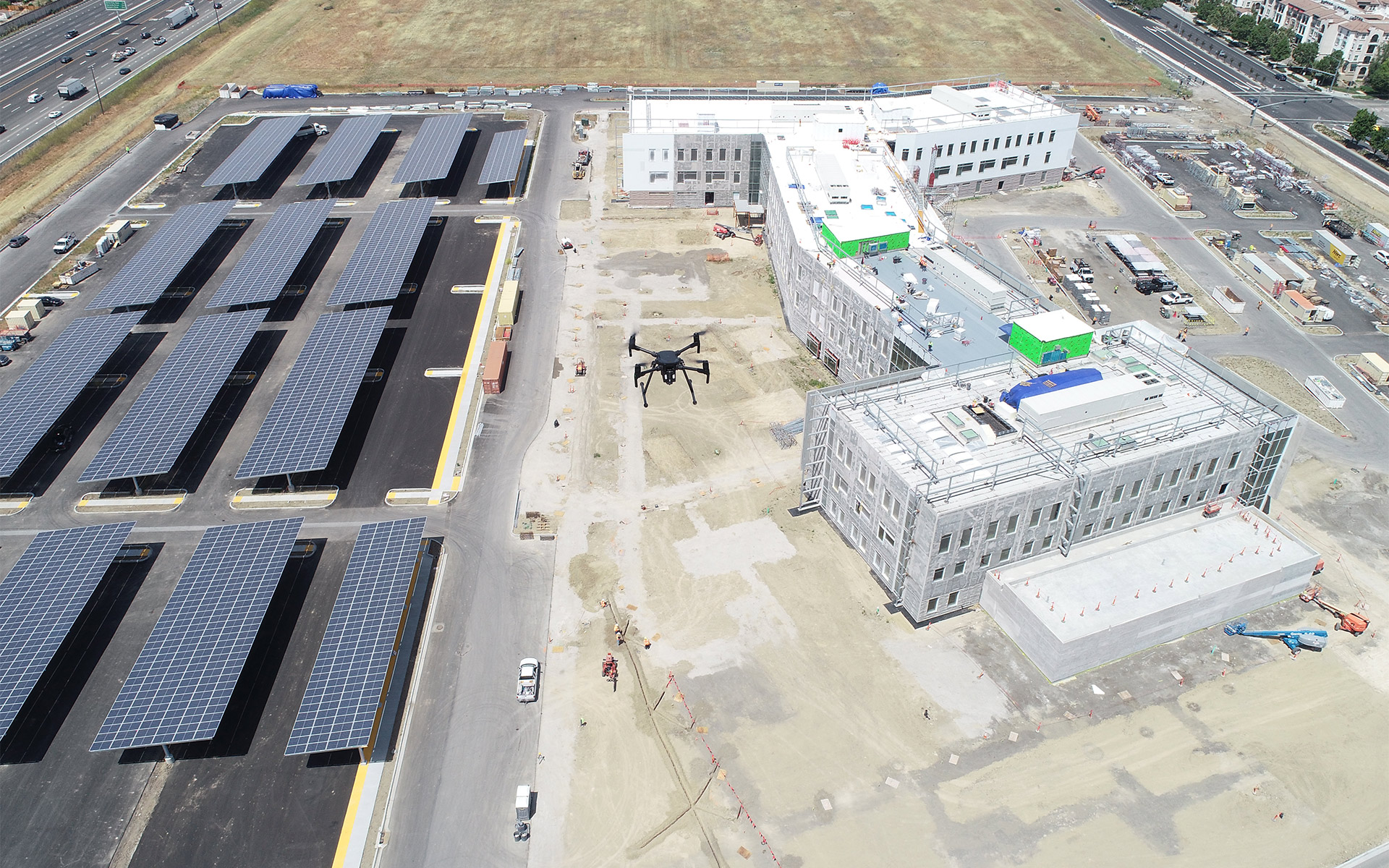

Winn observes that regulations worldwide are generally becoming more permissive, but acknowledges that some environments are still challenging for flying drones. “In New York it is extraordinarily difficult to get a permit to fly,” says Winn. “It seems counterintuitive, but drones are most useful for horizontal construction of bigger projects like highways, solar power plants, hospitals and data centres. We are working on a couple of multi-billion-pound stadium projects in the UK, where it's simply not possible for a site supervisor to be able to inspect and understand the whole site on a given day. But when drones have to fly higher for vertical projects, it actually becomes more complicated to use them.”

Kinghan predicts that if regulation is changed to allow pre-programmed drones to function independently, out of an operator’s line of sight, it will further enhance their usefulness. “On larger sites it could reach the stage where the contractor buys a drone, which takes off automatically from its pad at five o'clock every day to survey the site, then lands, and uploads its data for whoever needs it with no human intervention at all.”

Winn foresees an even more futuristic scenario. “There are already robots that can draw lines or drill holes. In the long run, flying robots will provide architectural data that will be processed to generate an action that will be executed by another robot. That is the next big jump. We believe that we'll have 100 to 1,000 times more use when we can actually get robots to be fully autonomous, so that instead of requiring a person on site, that person could be controlling 20 drones from a remote location,” he says. “We're just at the beginning of the adoption of robots in industry.”

“Instead of requiring a person on site, that person could be controlling 20 drones from a remote location” Mike Winn, DroneDeploy