_19%20Oct_Jamie%20Cullen.jpg)

Illustration: Jamie Cullen

Construction materials and the building sector are responsible, says the OECD, for more than one-third of global resource consumption. Feeding this insatiable appetite requires an enormous amount of energy, and produces an enormous amount of emissions – and waste.

More than half (55%) of the world's industrial carbon emissions are generated by the production of just five materials: steel (25%), cement (19%), paper (4%), plastic and aluminium (3%). Of these, the built environment industry is a primary consumer of cement, and consumes approximately 26% of aluminum, 50% of steel, and 25% of plastic.

At present, most built structures are simply demolished when they come to the end of their lifespan, and only 20-30% of this construction and demolition waste (CDW) is recycled or reused, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Consider that by 2025 we'll be generating 2.2bn tonnes of solid waste a year, and that CDW accounts for almost half of that total, and it's clear that this linear model of consumption is no longer sustainable.

The circular revolution

In place of this "take-make-waste" philosophy, the focus has been shifting over the past decade to a more sustainable model: the circular economy. At its core are three principals: to design out waste and pollution; keep products and materials in use; and regenerate natural systems. As we have seen, the built environment has been a key contributor to these issues and therefore has a crucial role to play in advancing the circular economy, which RICS has recognised through initiatives such as its collaboration with Arup and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

But despite the benefits of adopting a more circular approach being clear, it's also clear that there is still much progress to be made.

The context

To continue meeting the world’s societal needs, the urban built environment will need to grow by a massive 60% by 2050, according to the Circularity Gap Reporting Initiative.

In 2015, the total amount of materials needed to meet housing demand was 41bn tonnes. To put this in perspective, the accumulated building stock in the last two centuries until 2015 totals 832bn tonnes. This means that the accumulated stock is almost 20 times the size of the materials going into the sector yearly. Materials going into the built environment are predominantly concrete, asphalt, bricks, sand and gravel.

Thanks to the EU's Waste Framework Directive (WFD), which in 2008 mandated member states to attain a 70% CDW recycling by 2020, re-use rates across the continent have been consistently high – exceeding the target since 2016. However, the high recovery rates have mostly been achieved by using recovered waste for practices such as backfilling and low-grade recovery applications. At present, many of the material streams from demolition and renovation are not suitable for re-use or high-grade recycling, hampering efforts to achieve a truly circular economic model.

Slow progress

A truer reflection of progress can be found in the circular material use rate. Also known as circularity rate, this is the share of material resources used that came from recycled products and recovered materials, thus saving extractions of primary raw materials. In 2017 the EU's circular material use rate was 11.2%. This means that over 11% of material resources used in the EU came from recycled products.

Despite stellar performances of countries such as the Netherlands, which has a national mandate in place to become a circular economy by 2050, and Italy (up six percentage points between 2010 and 2017), the circular material use rate across the EU has barely improved in this period (up one percentage point), thanks to poor performances of other member states.

Building the case for re-use

A recent report by the Ellen Macarthur Foundation, Completing the Picture: how the circular economy tackles climate change, found that a circular scenario for the built environment could reduce global carbon emissions from building materials by 38% in 2050, due to a reduced demand for steel, aluminium, cement and plastic.

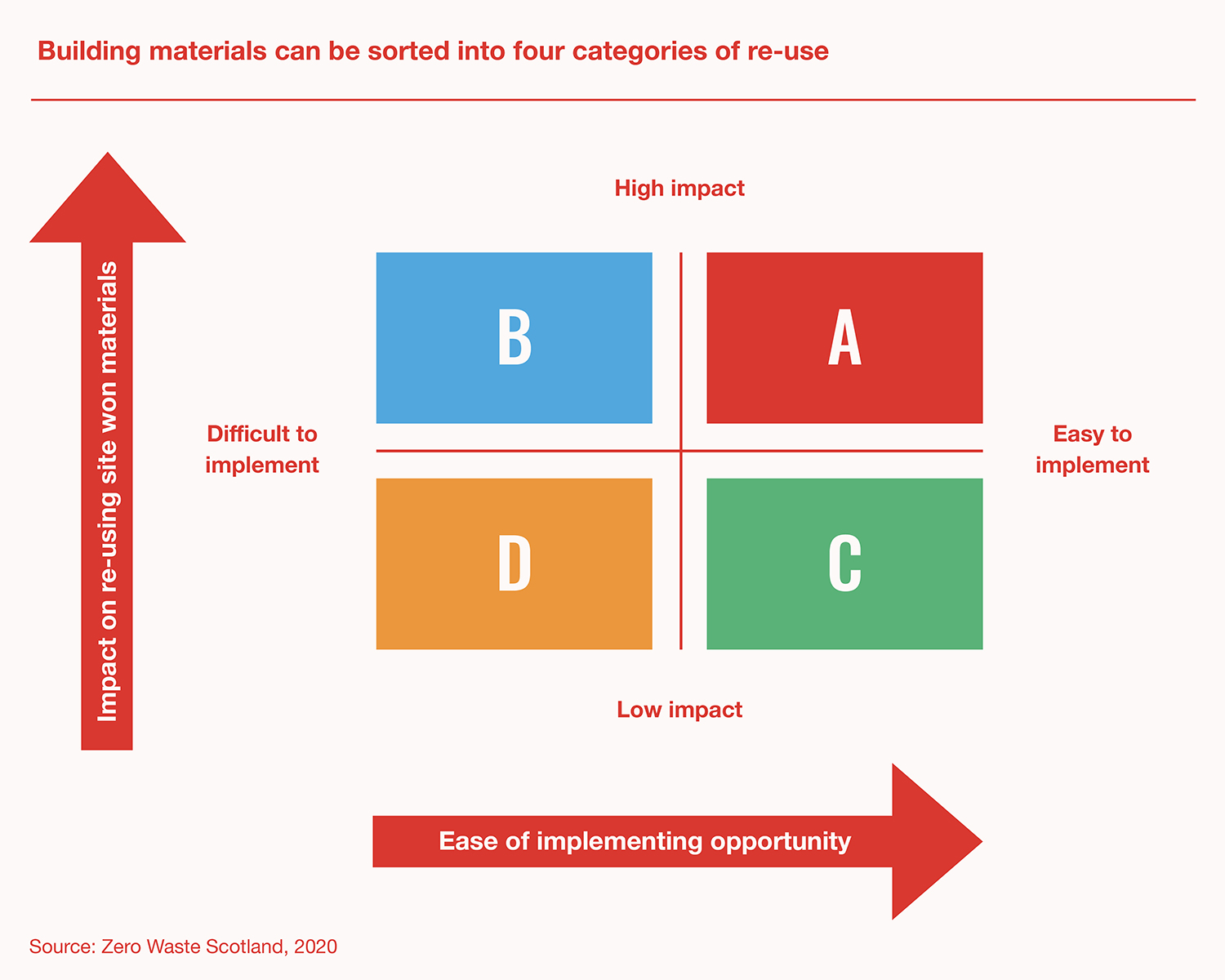

Research has shown that up to 25% of materials in residential buildings slated for decommissioning or deconstruction can be reused, while up to 70% can be recycled in some form. This means that only 5-10% of the materials have little or no value. As the below graphic shows, there isn't much that can't be re-used if the infrastructure exists to support it.

Over the next 12 months, leading up to the UK's chairing of the rescheduled COP21 conference in November 2021, Modus will be keeping the circular economy foremost in its thinking through a series of articles exploring the theme. If you haven't done so already, be sure to sign up to our monthly newsletter to ensure you get the latest stories straight to your inbox.