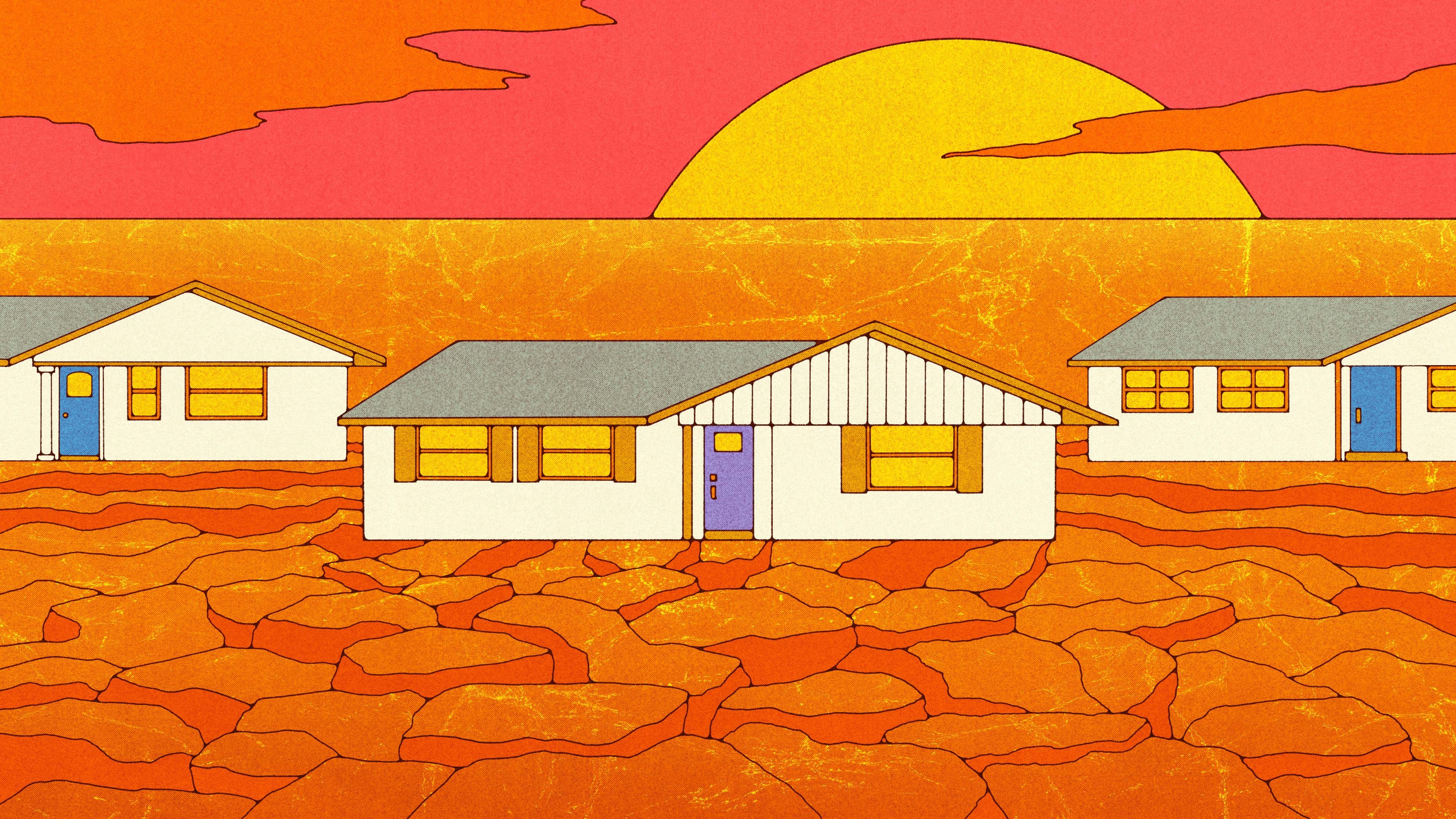

Image by Nicolas Ortega

Daytime temperatures in Temecula, California flirted with 38ºC in July, while summer rainfall averages less than 1cm in this city of 110,000 inhabitants, south-east of Los Angeles.

Damian Gavaghan FRICS, has owned a two-storey, 1,800ft2 house in Temecula (one of several cities that make up the booming Inland Empire metropolitan area) since 2011. Gavaghan calculates that he expends 60 gallons of water per minute to keep the grass green on his 8,000ft2 lot. Under the withering summer sun he must run his sprinklers for upwards of five minutes multiple times per day, adding up to hundreds of gallons of potable water just to keep the grass green.

Although California’s reservoirs were the fullest they have been in several years after a record wet winter, the parched region draws on overtaxed water supplies from the Colorado River and underground aquifers that do not replenish as quickly as reservoirs after years of drought.

Gavaghan isn’t naive, however. “Having grass in the desert is crazy,” he says. “It’s a dreadful waste of water.”

That’s why he’s seeking to replace his turf lawn with drought-resistant plants like lantana and lavender. Gavaghan’s preference is part of a growing landscaping movement among property owners in the Sun Belt region, which is both the fastest growing part of the US and the area most constrained by limited water resources.

The lush-manicured lawn is a cherished symbol that US homeowners inherited from British gardening traditions. While the climate of the eastern US is similar enough to the British Isles – harsher winters, but more regular annual rainfall – the arid south-west is hardly a natural habitat for turf. But postwar westward migration fueled a building boom that brought those landscape preferences to Arizona, California, Nevada and Texas.

“In densely built spaces that have a high level of land compaction, grass lawn with its three-to-four-inch root zone was something that could be laid down quickly, cheaply and easily. It could be watered and look mature right away,” says Jodie Cook, a landscape architect in San Clemente, California. “It’s become the utterly inappropriate default.”

Turf removal incentives

Neighbourhoods throughout the south-west plowed ahead with turf lawns for decades, water usage be damned. The tide began to turn in the 1990s with the advent of turf removal incentive programmes. One of the most notable schemes is run by the Southern Nevada Water Authority. Today, residents of greater Las Vegas can apply for a rebate of $3 per ft2 of grass removed and replaced with desert landscaping. The amount applies to the first 10,000ft2 of lawn, with additional square feet reimbursed at a rate of $1.50 per ft2. Local governments foot the bill, but generally find that the schemes pay for themselves with reduced water usage.

Dozens if not hundreds of local governments throughout the west and south-west followed suit with incentive programmes that typically range from 50 cents to $3 per ft2. A steady drumbeat of media coverage of the south-west’s so-called ‘megadrought,’ the worst in 1,200 years, increased urgency. So did the prospect of mandatory water cuts issued by the federal government if south-western states could not agree on how to divvy up dwindling Colorado River supplies.

Scottsdale, Arizona launched its scheme in 1998, but recently doubled the incentive to $2 per ft2. Participation in the programme tripled. “We were at the precipice last year of some drastic cuts,” says Scottsdale water policy manager Gretchen Baumgardner. “In the last three years we’ve stepped it up as the heightened level of understanding of the need to conserve water has been amplified.”

With more than 20 years of running its incentive scheme, the Southern Nevada Water Authority claims more than 210m ft2 of lawn have been ripped up, saving more than 170bn gallons of water. In just three years from 2014 to 2016, meanwhile, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which oversees 26 member agencies, funded the removal of 160m ft2 of turf.

“Having grass in the desert is crazy. It’s a dreadful waste of water” Damian Gavaghan FRICS, Terracon

What replaces the grass?

While those are impressive numbers, Cook cautions that too many schemes have focused more on grass removal and less on what replaced it. “All the water agencies wanted was to reduce landscape potable water use,” says Cook. “They almost didn’t care what went into the landscape after the lawn was removed. If you don’t tell people what to do, you’ll get plastic grass or gravel.”

For Cook, who teaches native garden design, this lack of foresight was a missed opportunity. She helped the Moulton Niguel Water District design the NatureScape programme, which helps homeowners create low-water native gardens in the wake of turf removal. The scheme is so popular there is now a waitlist among the district’s 170,000 customers who inhabit towns south-east of Los Angeles but closer to the coast than inland Temecula. While more modest in potential impact than the 2m customers served by the Southern Nevada Water Authority, Cook stands by the longer-term environmental impact of a scheme with firm regulations on what can replace turf.

“You’re taking away something that uses water but replacing it with something that has a negative environmental footprint,” she says. “Somebody eventually has to deal with that artificial turf problem.”

The power of homeowners associations

But the growing momentum in favour of lawn removal still faces stiff headwinds in certain corners. Gavaghan, for example, has found that installing a drought-resistant garden is far harder than he imagined despite the obvious water saving benefits. That’s because his home is subject to strict rules established by the neighbourhood’s homeowners association (HOA). An HOA is a self-governing private association common in subdivisions and planned communities, which are a typical style of residential property in the Sun Belt. In Arizona, California and Nevada over one-third of residents live in communities governed by HOAs. And historically, they have mandated grass.

“Lawn is 100% the default always,” says Cook. “[Master planned communities] are quickly built where every third or fifth home is the same. That sort of pre-packaged environment goes hand in hand with the rise of lawns.”

Neighbourhood at Camelback Mountain, Arizona

“The social contagion effect is very successful in changing behavior when it comes to turf removal” Jodie Cook, Jodie Cook Design

In Gavaghan’s case, his HOA tightened its rules around landscaping in 2022. The community’s architectural committee, composed of layperson residents nominally advised by a professional landscape architect, took a dim view of his plans, even though the HOA grows some of those drought-tolerant plants in the neighbourhood’s common areas. The statutory power of HOAs, meanwhile, leaves little room for argument.

“They have a planning capacity and also an enforcement capacity,” he says. “If you don’t get permission, they can put a lien (a legal claim) on your property and fine you.”

For Gavaghan, this dead-end stands in stark contrast to his surveying experience working at firms like Lloyds Bank, where alternative dispute resolution mechanisms existed when he and a customer disagreed. “HOAs are crying out for a third-party or ombudsman scheme,” he says.

Scottsdale leads with education when it approaches HOAs about turf removal. It can take upwards of a year, and a lot of staff time, to bring HOAs on board. “HOAs are tricky,” says Baumgardner. “We want to be really delicate.”

Carrot replaced by stick

After decades of carrots in the form of incentive schemes, however, the sticks are finally coming out. As of August, homebuilders in Scottsdale cannot install front lawns, so-called non-functional turf, in new construction and existing homeowners cannot expand the square footage of grass in their front yards. When the city surveyed residents about this proposed ordinance, 80% approved. By the end of 2026, Nevadans will no longer be permitted to use Colorado River water to irrigate decorative grass. That year is likewise the deadline for a similar California law, which will also require at least 25% native plantings to replace turf.

While laws that effectively make grass lawns illegal are a sea change for US communities, the new legislation only goes so far. Existing turf front yards in Scottsdale can remain, while single-family residences are exempt from both the Nevada and California laws. After all, lawmakers are elected by the public and telling homeowners what to grow in their gardens may not prove politically popular.

“The ban likely won’t affect the American obsession with residential lawns much,” says Cook. “That said, studies have shown that the social contagion effect is very successful in changing behavior when it comes to turf removal.” She points to a study showing that for every 100 turf removals using water agency incentive payouts, an additional 132 nearby properties removed their lawns without a rebate.

As the south-west’s megadrought shows no signs of abating, California has set a goal to remove 500m ft2 of lawn by 2030. The message is clear: grass lawns, your days are numbered.