Illustration by Fabrizio Lenci

Last October an Oregon fish biologist found a Chinook salmon in a tributary of the Klamath River, some 230 miles inland. Hundreds of millions of salmon return from the Pacific Ocean annually along the West Coast, but this particular fish’s location was a minor miracle. No salmon had been spotted here for more 110 years. Not since the first hydroelectric dam was constructed along the Klamath in 1912.

During the 20th century, the US, like many industrialised nations, harnessed river power for energy production, irrigation and flood control. That era’s zeal for large-scale hard infrastructure disregarded natural ecosystems and the cultural significance of free-flowing rivers to the region’s original inhabitants. On the Klamath River alone, six large dams were built over a 50-year stretch that blocked upstream fish migration. The dams’ construction was devastating for five federally-recognised Native American tribes whose cultural identity is intimately connected with salmon — some of whom had signed treaties with the US government affirming their right to fish.

But in the space of a little over a year beginning in June 2023, four of the dams came crashing down in the largest dam removal project in world history. For the first time in a century, the Klamath was free.

Today hydroelectric dams are facing a global reckoning as alternative sources of energy, including wind and solar, provide an alternative to fossil fuels. It is also the case that the environmental and cultural impact of damming rivers has become more broadly understood. Dam Removal Europe has supported more than 8,000 dismantlings, while American Rivers estimates that about 2,100 dams have been removed in the US since 1912.

“The narrative has changed around dams,” says RICS Director of Land and Resources James Kavanagh MRICS. “We’ve had a blind spot about where we’ve placed them and how we’ve only measured their economic value.”

The Klamath River flowing next to the the Yurok Tribe tribal headquarters

A river captured

The Klamath River drains over 12,000 square miles from its headwaters in Oregon’s high desert through mountain ranges before emerging into temperate rainforest along the California coast. The Yurok, Karuk and Hoopa Valley tribes, Shasta Indian Nation, and the Klamath Tribes confederation all live in the Klamath Basin and historically have sustained themselves on what was once the country’s third-largest salmon bearing river.

But westward expansion, from gold rushes to homesteaders, encroached on their traditional lands. The US government forced the tribes onto reservations and signed treaties affirming their right to fish.

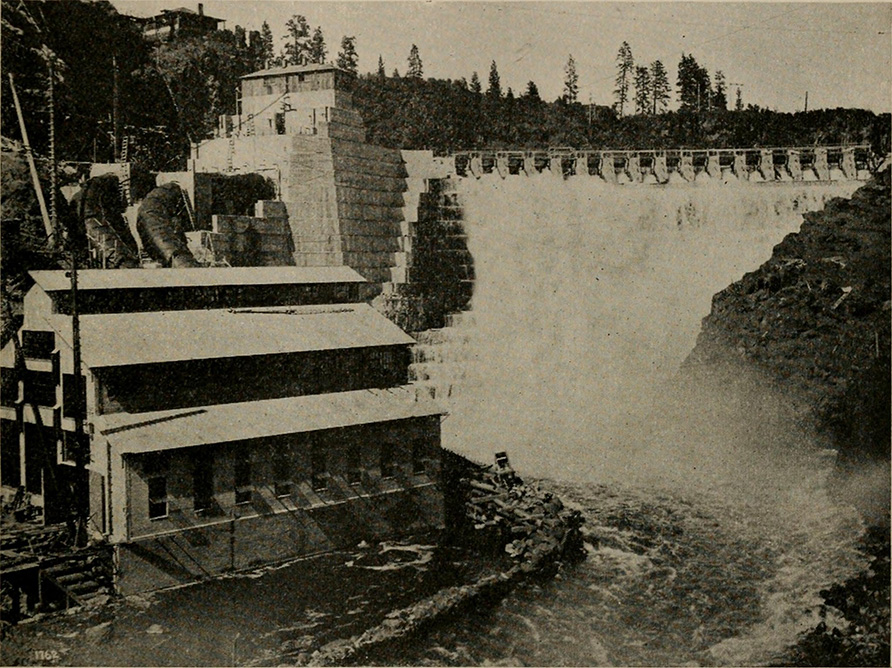

In the early 1900s, the California Oregon Power Company (COPCO) engineered and built a series of four hydroelectric dams near the border between the two states, which effectively ended salmon runs in the upper Klamath Basin. Facing diminished salmon numbers as a result, government officials restricted the tribes’ right to fish on conservation grounds even while allowing commercial and recreational fishing to continue. Some tribal members defied the orders and faced violent reprisals from law enforcement.

The last of the dams was completed in 1962, just before the dawn of the modern environmental and indigenous rights movements. By the 1970s, the tide had begun to turn. California, and later the Congress, designated portions of the Klamath as a Wild and Scenic River. The Supreme Court made rulings in support of tribal fishing rights. But the dams, as well as logging and offshore commercial fishing, continued to hamper salmon runs. Favourable laws and rulings did not change the ecological conditions in the water.

A turning point came in the early 2000s. PacifiCorp, the modern-day utility that owns the Klamath dams, filed to renew its federal dam operator license in 2000. Two years later, some 68,000 salmon died at the river’s mouth, the result of warm water temperatures and low river flows that likely caused a bacterial outbreak. At the time it was the largest documented fish kill in the US West and galvanised both environmental and tribal advocacy around the Klamath dams.

The environmental and indigenous allies waged their campaign in the court of public opinion, staging headline-grabbing protests in the US and Scotland outside the headquarters of Scottish Power, which owned PacifiCorp until selling the utility in 2005 to Berkshire Hathaway. The Klamath Dams had become a political hot potato — and not all that valuable to the utility’s customers, generating less than 2% of PacifiCorp’s energy portfolio.

In 2010, PacifiCorp acquiesced and signed a settlement agreement with tribes, local governments and federal agencies that charted a path towards dam removal. Nearly 100 years since the first engineers began figuring out how to bottle up the river, blueprints were unrolled once again with the goal of figuring out how to let it loose.

Copco Number 1 Dam, built in 1922 and dismantled as part of the Klamath River Renewal Project.

“The narrative has changed around dams. We’ve had a blind spot about where we’ve placed them and how we’ve only measured their economic value.” James Kavanagh, RICS Director of Land and Resources

How to free the Klamath

Fourteen years passed between the settlement agreement and the August 2024 breaching of the Iron Gate Dam, which tribal members celebrated with hoots and hollers as they watched heavy machinery turn concrete into rubble until the waters pushed through unimpeded.

Why so long? Oregon State University professor of biological and ecological engineering, Desirée Tullos says, “The more people get involved, the more complicated a project is.”

The Klamath Dams involved two states, five tribal nations, federal regulators, a major utility and dozens of riverfront towns anxious about what such a massive change would mean to their communities, from the loss of reservoirs that serve as beloved recreational lakes to changing wildlife patterns. Balancing competing interests nearly derailed the process — indeed, PacifiCorp ended up signing a revised settlement agreement in 2016 that became the official road map for what eventually resulted in dam removal.

Two critical elements ushered the dam removal along: money and governance. California voters authorised billions in bonds for ecosystem and watershed restoration projects in 2014, meaning the project tapped into $250 million. Separately, PacifiCorp put a surcharge on its customers’ bills and raised an additional $200 million. These combined funding streams provided the $450 million necessary to pay for dam removal and post-removal restoration. Meanwhile, liability-shy Berkshire Hathaway transferred the dam license to the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), a nonprofit chartered solely for the purposes of administering the dam removal and restoration.

Critically, the tribes had a seat at the table. “We were involved every step of the way in getting to dam removal,” says the Yurok Tribe’s Fisheries director, Barry McCovey, Jr. “It was cathartic to do the work.”

Tribes helped set up the KRCC’s structure. A Karuk tribal member serves as vice-president on the KRCC’s board of directors, while a Yurok tribal member is a board member and the KRCC’s general counsel. Those indigenous perspectives informed key decisions such as instructing the project’s main contractor, global infrastructure firm Kiewit, to drain the reservoirs during the fall and winter months when rainfall will assist in flushing decades of accumulated sediment. Tribal input also informed the brass tacks of post-removal restoration, a massive undertaking to plant 17 billion seeds and 300,000 trees and shrubs to restore native vegetation.

“Having someone in the room that sees the world through our lens can be helpful when you get down to the ground,” says McCovey.

Lessons for surveyors

The scale of the Klamath removal is flashy, but most future dam removal projects are miniscule by comparison.

“Dinky little dams exist everywhere across the landscape,” says Tullos, pointing to the 91,000 listed entries in the National Database of Dams. Most of those are 10m or lower, like the Savage Rapids Dam on Oregon’s Rogue River, which took 30 years to remove. “Complexity doesn’t necessarily go away as the project gets smaller,” she says.

Having an entity with broad representation like KRCC helps immensely, but the enormity of the Klamath project also motivated such a solution. “KRCC is a great strategy, but it’s not cheap,” says Tullos. “We have no plans for the small, privately-owned dams or the big dams. We have taken for granted that our dams and our water are essentially free and it’s not going to continue to be that way.”

How to measure such costs is a new frontier. “Surveyors are becoming a lot more understanding of how social, environmental and cultural values work,” says Kavanagh. “These are difficult to arrive at because there are no comparisons, which is what valuations are typically based on.”

RICS recent research on natural capital, carbon markets and valuing biodiversity are good start points for chartered surveyors to explore. But, regarding indigenous rights specifically, surveyors can also consult the experience of the Australian High Court’s 2019 ruling providing AU$2.5 million ($1.55 million) in compensation to aboriginal people impacted by mining operations near Timber Creek starting in the 1950s.

Of course, weighing such cost benefits does not always result in the best outcome for indigenous peoples. While the World Bank and European Investment Bank declined to fund Ghana’s Bui Dam due to environmental impacts on three tribes, the Chinese government eventually stepped in.

While geopolitics are beyond the call of duty for most chartered surveyors, due diligence around so-called non-market values is nevertheless an increasingly vital skill that requires thinking beyond traditional valuation and embracing qualitative tools such as public meetings to complement technological tools like drones, satellite imagery and biodiversity benchmarks.

“Measuring non-market values will not always result in just a number,” Kavanagh says. “Surveyors have to be intellectually flexible to deal with that possibility.”