When the coronavirus pandemic swept through the UK – and with it, a rolling series of lockdowns restricting business activities – local authorities found themselves very busy processing planning applications. Restaurants closed and reemerged as commercial kitchens. Gyms shuttered their doors and rented out equipment to their members.

Changes of business use were recorded on an application form, albeit one filled out by humans who can write the same instructions in a variety of ways. Where one person may write “From A1 to A3” on the form, another may write “To A3 from A1.” Those two entries on a planning application mean the same thing but are phrased differently and make producing a neat dataset more challenging.

For Ian McGuinness FRICS, head of geospatial at Knight Frank Research, this quirk of human language was a puzzle to be solved. And he would solve it with the treasure trove of data provided by the sudden nationwide change to the composition of the high street. His team employed machine learning to design a technique that can read like a human and process large quantities of data.

“We were able to spot very high level patterns in changes in planning activity across all the high streets in the UK, but only by trawling hundreds of thousands of data points and looking for nuance around language,” says McGuinness.

This sophisticated level of analysis is increasingly common in the property sector. “We’ve gone from a sector that has collected a relatively small amount of data about rents, yields, type and size of building, quantity, and costs, to now being faced with huge volumes of data without necessarily having the maturity or structure,” says Dan Hughes, director of Alpha Property Insight.

That shift brings with it a host of ethical implications that industry and government alike are only just beginning to address. Hughes serves on the steering committee of the Real Estate Data (RED) Foundation’s Data Ethics Steering Group, which has drafted six principles as a starting point for surveyors and firms to draw on as they negotiate this new world. Key to the principles are four overarching questions: What can I collect? What am I allowed to collect? What should I collect? And how should I use it?

He argues that surveyors should start paying attention now, as the possibility of ethical lapses is fast approaching. “Most people in real estate either think GDPR covers it or it’s someone else’s problem or a problem that doesn’t exist at all,” he says. “But it’s coming quite fast in the next five to 10 years. Our data ethics principles are just a starting point.”

Local authorities caught in the middle

In 2019, property developer Argent found itself in the crosshairs when British media reported that surveillance cameras at King’s Cross Central were connected to facial recognition software used by the Metropolitan police. The real estate firm and the police service made their arrangement in secret, violating public trust. The developer ultimately backpedaled and pledged not to use facial recognition software at the mixed-use property. “As far as I know they were using [the technology] completely ethically, they just hadn’t thought through the implications,” says Hughes.

Sue Chadwick is a planning lawyer by training and a strategic planning advisor with Pinsent Masons LLP, who was a fellow at the Overseas Development Institute in 2020, focusing on data ethics. She says that both private firms and the public sector will be facing this kind of scrutiny if they don’t proactively address the implications of these powerful new technologies by engaging in careful and transparent deliberations.

In one hypothetical example that may soon become reality, she described the myriad of ethical questions that might arise if a local authority sought to procure a chatbot to staff its planning service: What is the algorithm driving the chatbot? Does the chatbot properly account for the ethnic mix of our population and accomodate our strong regional accent? Is there a human at some point in the loop?

Chadwick says that if a local authority has gone through a robust procurement process it can say to the public: “We are going to use this chatbot 24 hours a day and make it easier to get service, but here are all the ways this technology can go wrong. Do we still want to proceed?” Just as important, the local authority can pilot the AI-driven chatbot and return to the public at a later date to gauge public reaction.

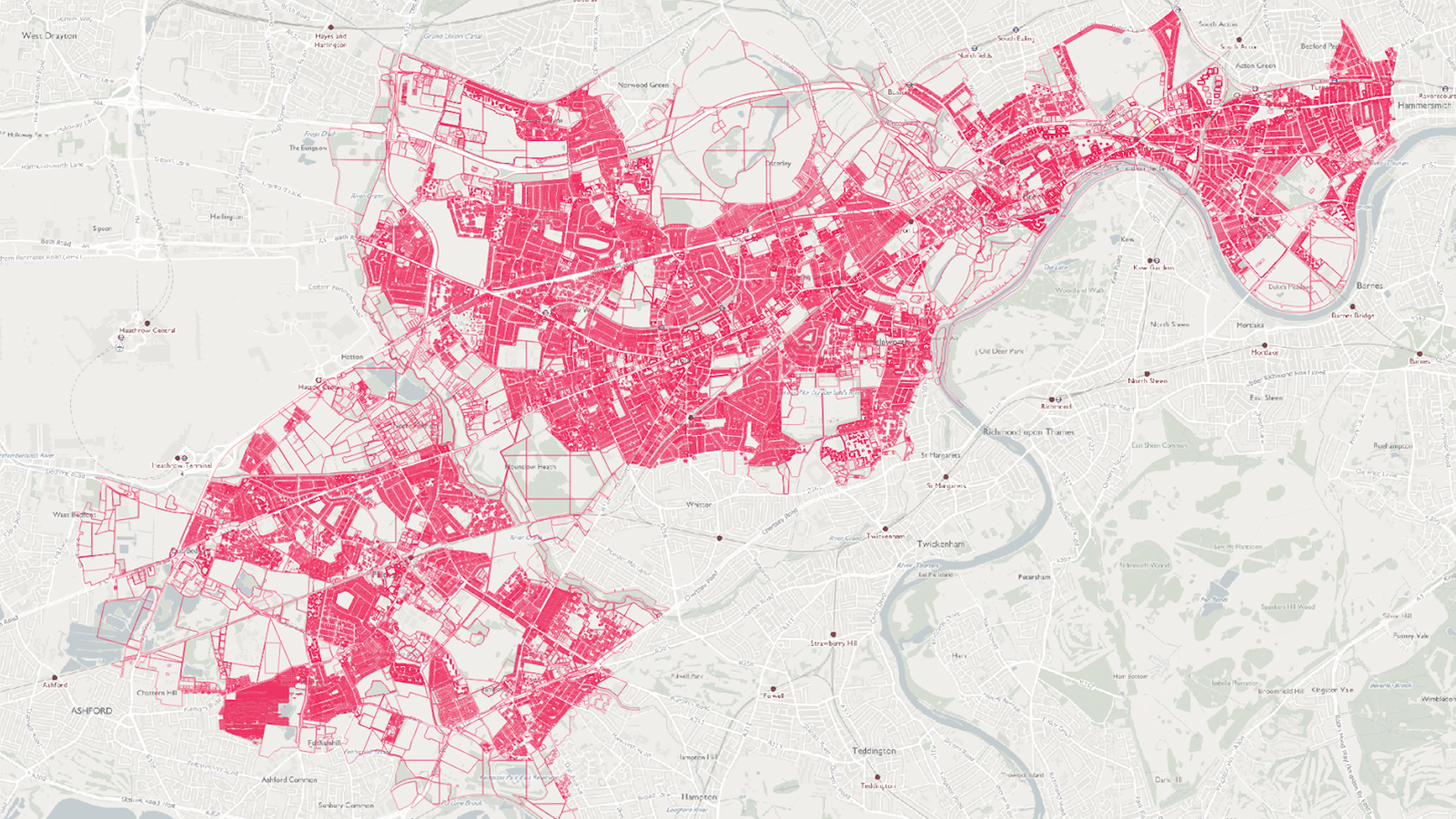

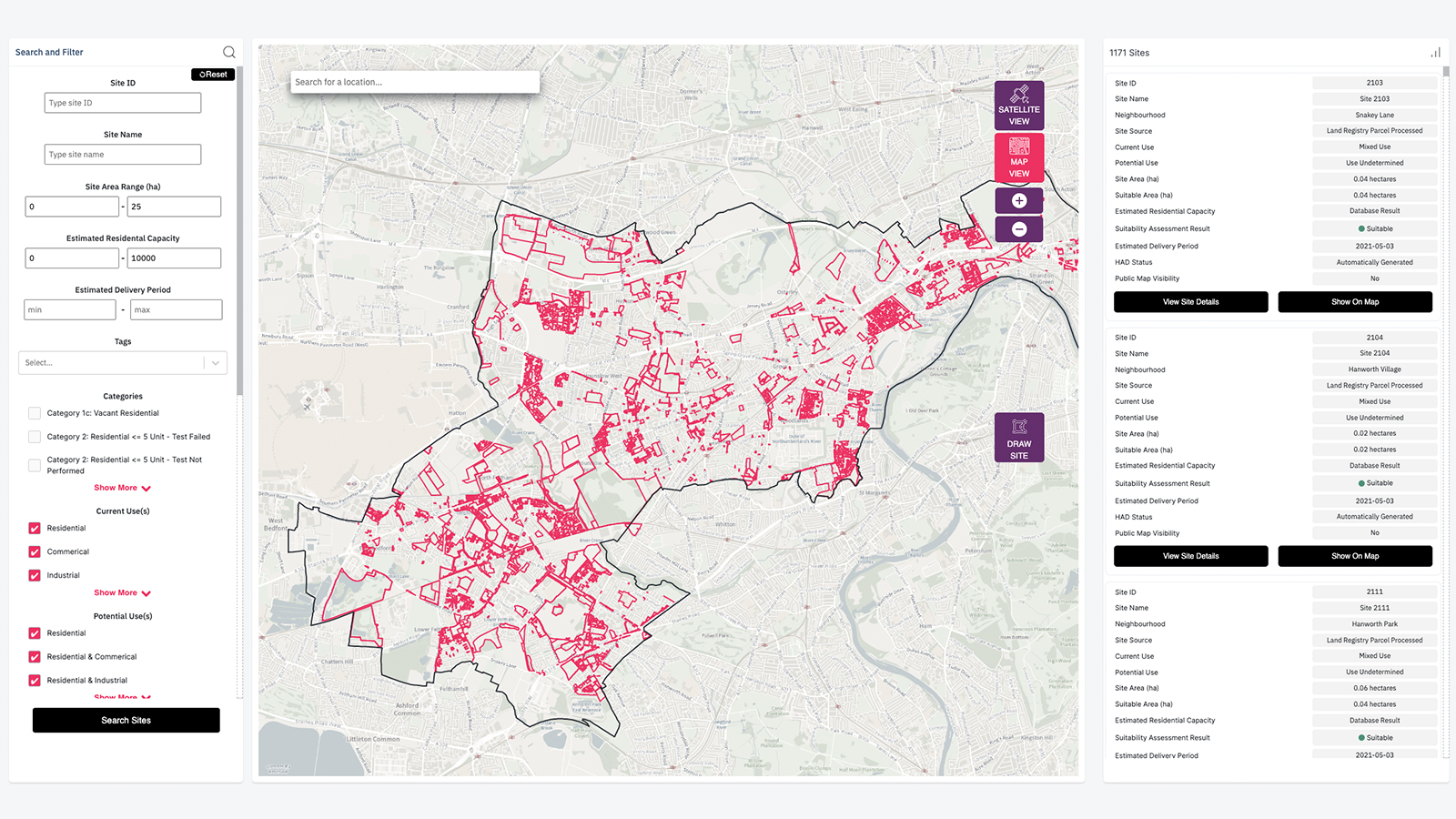

Some local authorities are already on the vanguard. In the UK, the London borough of Hounslow is facing an ambitious deadline issued by London mayor Sadiq Khan: build 17,820 new homes in 10 years, with 2,800 of them located on sites less than one-quarter hectare. To tackle this challenge, Hounslow issued a tender for a private consultant to analyse land parcels and identify suitable options.

“Our industry data picture is much more fractured than most people would like to concede.”

Photo: Urban Intelligence

Using data to determine suitable land for housing in the borough of Hounslow, London

Hounslow gave the tender to data-driven property analysis specialist Urban Intelligence, which since 2014 has been steadily amassing a comprehensive database of UK planning information. The firm combed through every land parcel in the borough, resulting in 115,000 sites considered for their suitability for future housing.

“It opens up the field for a lot of potential landowners,” says Urban Intelligence’s Daniel Mohamed. He argues that this more objective and universal approach is more ethical than the old way of doing business, where only a small subset of landowners are familiar with the call for sites process.

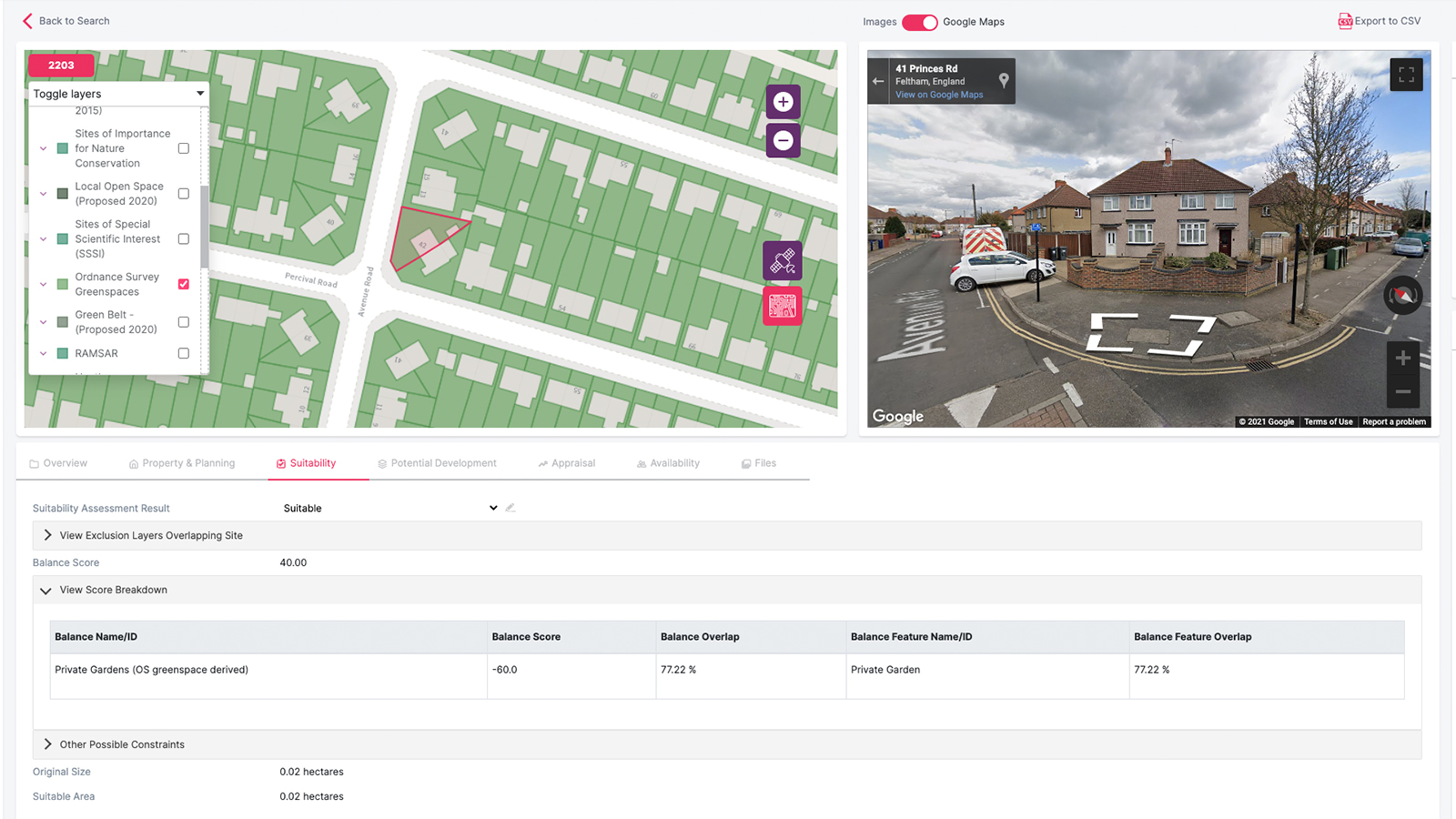

The firm also used geospatial data to create a scoring system that allows for a more nuanced analysis of site suitability than a traditional “traffic light system” ascribing red, yellow, and green to sites. To curb any potential biases, Urban Intelligence consulted with the borough council and a group of professional planning officers to decide which geospatial factors would be scored and weighted. These include heritage value, flood risk, and environmental constraints.

“We had not fully considered the AI approach before and we had never ascribed a score,” says Borough of Hounslow urban design project officer Louisa Facchino-Stack. “Other boroughs are doing a manual approach and looking for tiny plots of land the old way. We were pleasantly surprised by the AI approach.”

Hounslow’s experience may be a one-off, however, as a lack of systematised information stymies more complex deployments of machine learning and artificial intelligence.

“We are nowhere near being able to rely on AI to work out where the next housing development should go,” says Knight Frank’s McGuinness. “Our industry data picture is much more fractured than most people would like to concede.”

The firm combed through every land parcel in the borough, resulting in 115,000 sites considered for their suitability for future housing.

The ethics of data collection

Ultimately, Brussels may end up setting the global standard for AI regulation. The European Union created a new global norm for consumer data privacy when it passed the General Data Protection Regulation. A similar industry-changing move may take effect with a new AI directive that Brussels floated in April. Although the proposed regulations are not specific to any sector, Chadwick cautions, “lots of things in the regulations will eventually hit the property sector.”

Even as the regulatory framework continues to be built, the sector is already looking at ways to prepare for this emerging concern. Last year RICS announced proposed changes to its Rules of Conduct, including a new focus on technology and data ethics, which will require the attention of every firm’s ethics officer.

“We don’t need a separate person looking after data ethics, but is whoever looks after this at your company equipped to make sure they are building data ethics into their job title?” asks Peter Bolton King FRICS, who chairs the RED Foundation’s Data Ethics Steering Group.

At Knight Frank Research, McGuinness is keeping those issues front of mind. Especially the balance between the public and private sector, drawing on his former role in planning policy.

“There is a public interest dimension to the procurement of evidence that overwhelms the standard the public sector can consider,” he says. “There is no ability to cross-examine findings that are compelling, irrefutable and overwhelming coming out of the private sector, such as development and location of major infrastructure.”

The risk of the private sector harnessing technology that outpaces the ability of the public sector to keep up could provoke a backlash and is yet one more reason why surveyors should start integrating data ethics principles into their practice now.

As Chadwick advises: “If you create a bit of governance now you’ll be ready for the future, cover your bases, and have a positive story to tell about AI.”