In the world of architecture, a humble napkin is almost as famous as one of London’s defining buildings.

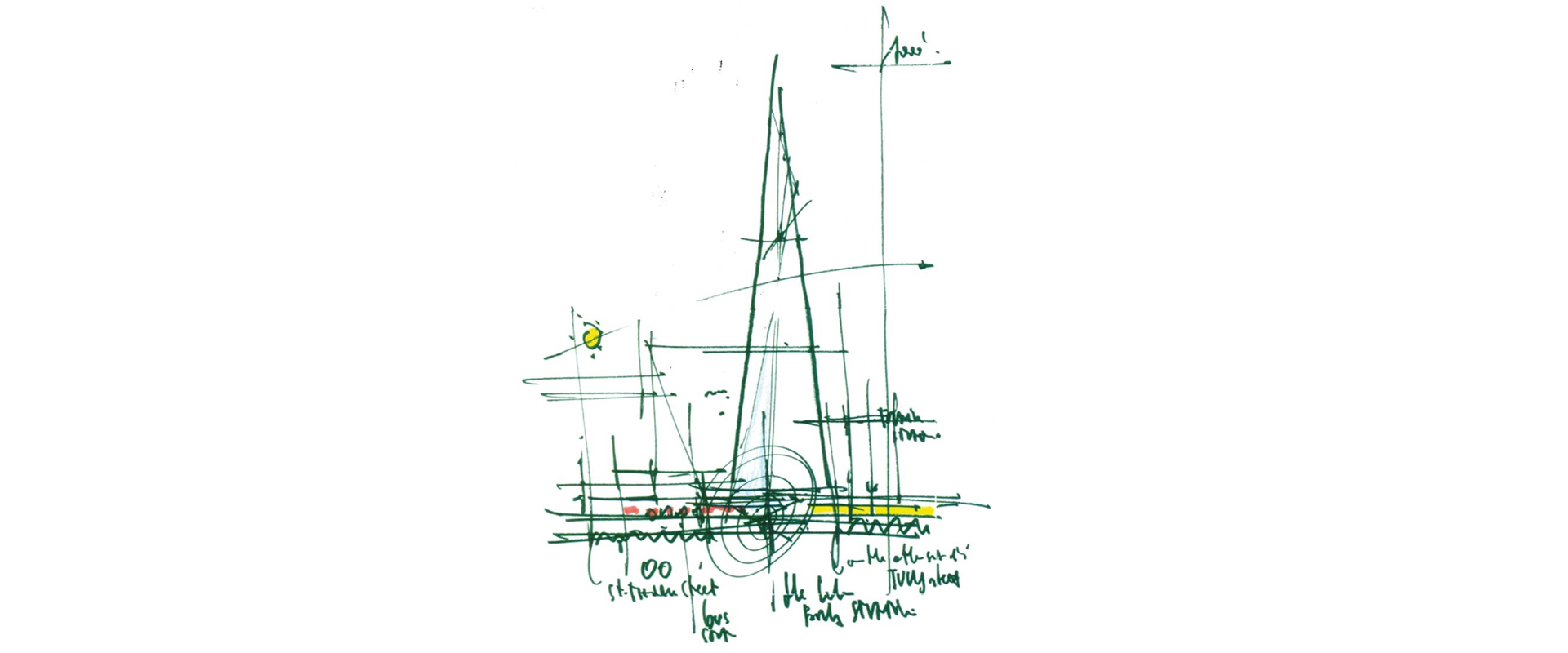

It was in March 2000, when property developer Irvine Sellar had lunch with famed architect Renzo Piano – the man who was part of the team that designed the Pompidou Centre in Paris. Sellar wanted to talk about a development in the capital, and at one point during the meal, Piano scribbled designs for the first sketch of The Shard at London Bridge on the paper napkin.

“This thing came very quickly,” Piano has been quoted as saying about the original drawing for the landmark skyscraper. The result was a partnership that created the 72-storey Shard, completed in 2012, and opened in February 2013.

During that legendary lunch, no one could have known the impact the building would have, not only on the London Bridge area, where it sits above the bustling rail and bus terminal, but also on the capital overall.

In years afterwards, Piano quipped about his napkin sketch: “I don’t want to create a mythology.” But coming after the 2008 global financial crisis, a bit of mysticism and hope was needed. The Shard was the capital’s first large-scale, mixed-use skyscraper. Despite raised eyebrows at a design that wasn’t to everyone’s taste, it signalled the economic recovery of London.

Some said it stabbed London in the heart, others, that it destroyed the scale of the city, but supporters hailed it as a jolt of the modern.

Piano's napkin sketch of the Shard

A vertical city

One of Europe’s tallest buildings, it has several entrances at ground level and next to the train station. Inside the 72 habitable floors are a 26-floor office complex, six restaurants, cafes and bars, the 19-floor five-star Shangri-La Hotel, 13 floors of residential apartments and the UK’s highest viewing gallery, which in its first year of opening attracted 900,000 people.

“The Shard represents a vertical city … and is a focal point for the transformation of London’s South Bank into one of the capital’s most diverse and culturally rich submarkets,” says Martin Lay MRICS, head of London capital markets at Cushman & Wakefield.

Transformation is the key word. Not only has Piano and Sellar’s glass tower made an impact itself, but the effect has rippled out to the immediate area now collectively called the Shard Quarter. “From its very conception, The Shard was designed to be a beacon for modern London. The building itself was just the first phase of redevelopment in Shard Quarter,” says Derek Rossenrode, general manager of Shard Quarter, which is home to media company News UK’s 17-storey headquarters, The News Building, and Shard Place, the 27-storey, 176 apartment residential development, set to be completed this year.

The building’s impact is also felt beyond its immediate surroundings. At Borough Market, the famous London landmark dating back to 1756, The Shard has brought an influx of new customers. But Kate Howell, director of communications and engagement at Borough Market, argues that it was the revival of Borough and Bankside as a destination for food and culture in the early 2000s that drew The Shard here – not the other way round.

“The Shard represents a vertical city … and is a focal point for the transformation of London’s South Bank” Martin Lay MRICS, Cushman & Wakefield

“The Shard was designed to be a beacon for modern London” Derek Rossenrode, Shard Quarter

Part of a transformation

Bankside was a mixed-use area of dreary office blocks and light industrial units, whose transformation began with the arrival of the Shakespeare’s Globe theatre in 1997, before the opening of the refurbished Bankside Power Station as the Tate Modern in 2000 secured the area’s rebirth.

The Shard then became the visual landmark of the wider regeneration. And Howell admits it has brought mixed fortunes. “In some respects [The Shard] has been good for us and our traders – more residents and workers mean more potential shoppers.

“Some businesses in the Shard Quarter Development have become big supporters of the Market, and there are lots who are now regular shoppers, and come to our events. That is all positive.”

However, Howell says the increase in office workers coming to the area has also caused “some soul searching.” She says: “Demand for street food at lunchtimes increased dramatically as new offices opened, but this market has always primarily been a produce market. Our challenge has been to satisfy this demand without swamping our produce traders or compromising on food quality.”

“It is now one of the most compelling places for business and tourism in the world” Nadia Broccardo, Team London Bridge

Construction of the Shard

Stalls of Borough Market in the shadow of the Shard

Entrance to London Bridge station under the Shard

An evolving city

Changing and adapting is what London Bridge has done over the last 10 years. Even the train station, one of the capital’s busiest and oldest, began a £700m refurbishment in the same year The Shard completed in 2012, finishing in 2018.

“It is now one of the most compelling places for business and tourism in the world and The Shard has been a significant driving force in this,” says Nadia Broccardo, chief executive at Team London Bridge.

Sellar, who died in 2017, kept the famous napkin in his office. In an interview a decade ago, he said of Piano: “He saw the beauty of the river and the railways and the way their energy blended and began to sketch in green felt pen on a napkin what he saw as a giant sail or an iceberg.”

As it stands pointedly in the London skyline, The Shard shows how something that started so quickly and simply as a sketch can have a transformative impact on everything and everyone around, becoming an enduring symbol of the city worldwide.