Photo by Mark Hadden

Two buildings stand on Amsterdam-Noord that represent an industrial past and a march into the future. They have put a forgotten side of the city back on the map.

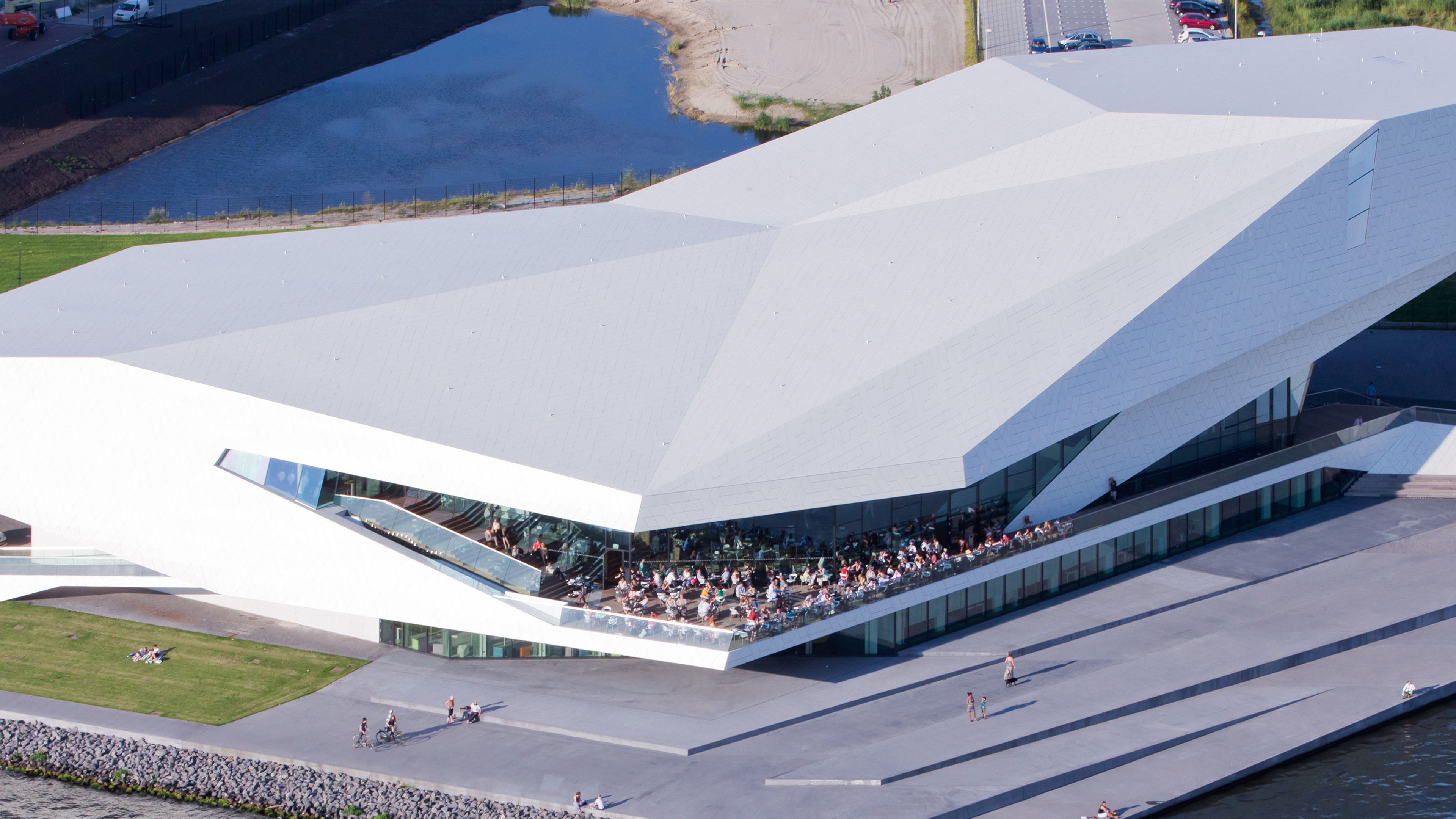

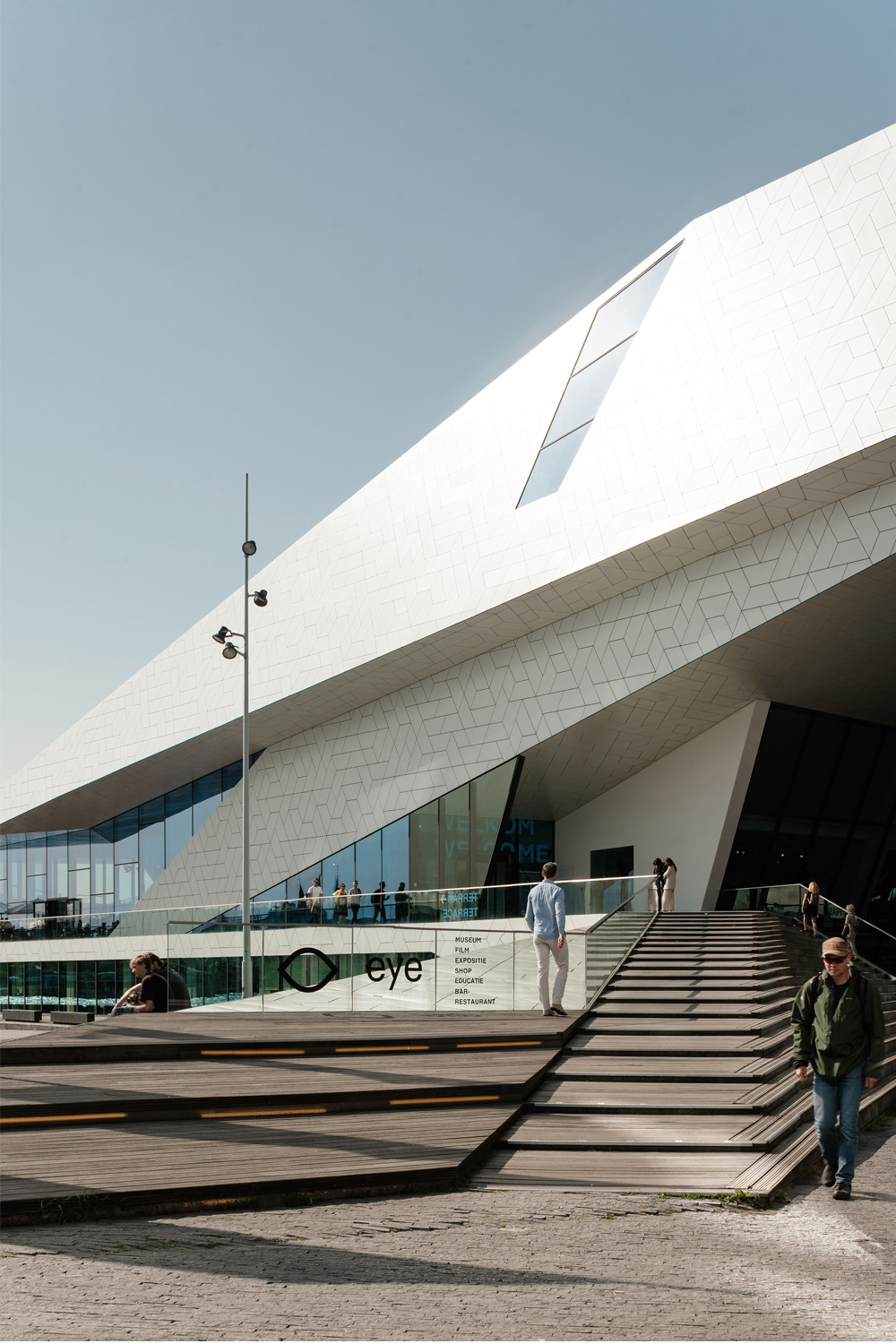

The EYE Filmmuseum opened 10 years ago and is today a landmark in the city’s Noord district, perched like a giant white spacecraft on the water’s edge. Next to it is the Overhoeks Tower, a 1970s relic and remainder of what was the sprawling former Royal Dutch Shell research site.

The past had a direct design inspiration on the present when regenerating 20ha of Shell’s vacated, and previously closed off, industrial land directly across the river from the central station in the mid-2000s. “When we went there was nothing urban or anything to do with the city; there was only the river and the strange Overhoeks Tower, which we liked a lot,” says Dietmar Feistel from the architects Delugan Meissl, designers of the futuristic-looking EYE.

“We thought whatever we are going to build there should somehow communicate with this existing tower, which was the only high-rise on the northern bank of the river. Therefore, we wanted to ‘shake hands’ with this building.”

Taking inspiration from the white concrete legs of the tower, Feistel says: “If you look closely you can see on the ground floor – the legs of the building are connected to ours in colour, and in its geometry. That was one of the ideas.”

The resulting EYE, loathed by some fellow Dutch architects, put Amsterdam-Noord on the map – literally.

Photo 1 by Iwan Baan. Photo 2 by Mark Hadden. Photo 3 by Ralph Richter

Enlarging Amsterdam

“Maps of the city from the past, show the central station and then the half circles of the famous canals. Amsterdam-Noord was never featured. But since we have been here, and since the redevelopment of this part of town, it has opened and enlarged the city of Amsterdam,” says Sandra den Hamer, director, EYE Filmmuseum. She has been involved in the museum since its conception as a small, coloured spot on a wider development plan.

At the end of the 1990s, the Shell laboratory moved to new facilities on the north-west of the site after 70 years, freeing up swathes of land ripe for redevelopment. Mainly industrial, it was called the city’s back yard, the ugly duckling. “It was a blind spot on the landscape where no one could go,” says Feistel.

That was set to change when a few years later, the EYE Filmmuseum began looking for a new home after a hefty rent increase on the Vondelpark Pavilion, where it had been since 1975. In 2007 Rien Hagen, former EYE director and den Hamer’s predecessor, identified the Noord area, and plans were drawn up with the team of the City of Amsterdam, Dutch Ministry of Culture and ING Bank, which had bought the land from Shell.

“They could realise their dreams of a new building, while the city council wanted to redevelop and reenergise Amsterdam-Noord,” says den Hamer. Plans included 2,200 residential units, and 130,000m2 of office, retail, and cultural space, including the EYE.

“The river stopped being a barrier between the city itself and the northern areas” Dr Esra Kurul, Oxford Brookes University

“Dutch architects have a clear philosophy of architecture: it’s very strict, straight, logical – and our building was not logical” Dietmar Feistel, Delugan Meissl architects

Photos by Mark Hadden

Global recession

“In 2007, there were artist impressions of the whole area where you saw the museum on the riverside, then the residential buildings, hotels, a completely new area,” says den Hamer. “But when we opened, we were here all by ourselves.”

What wasn’t in the artist impressions, or on anyone’s development agenda, was the 2008 global recession. Worldwide banks took a hammering and as the EYE was being funded by Dutch bank ING, it made for difficult times. “The ING bank was shaken,” says Feistel. “There was no money left … they would have liked not to have built the building, and we had to struggle, and fight with them a lot about budgets.”

The battle was worth it. Development got underway in 2009, and the EYE opened in 2012. Inside is a 1,200m2 central exhibition hall, the heart of the building, four film theatres and a café-restaurant with a terrace. The design was certainly not loved by all though.

“We were criticised for our shape,” says Feistel. “Dutch architects have a clear philosophy of architecture: it’s very strict, straight, logical, and our building was not logical – it was a very personal and subjective form. It’s not describable: it is like it is,” says Feistel.

“But it’s obvious people love the building, and that’s enough for us.” Between 2013 and 2019, the EYE welcomed 700,000 visitors each year annually, when it was originally hoped there would be 200,000.

Interior. Photo by Mark Hadden

Cafe-restaurant. Photo by Denis Guzzo

A catalyst for regeneration

Despite the EYE’s construction, fallout from the 2008 crash meant other buildings were delayed. In the last few years that has changed.

“We now have all the primary schools in this part of town doing film education workshops, and we invite all the kids from the schools to the museum: there’s a lot of outreach to the local neighbourhood,” says den Hamer.

The Overhoeks Tower was rebranded as A’DAM Toren, for ‘Amsterdam Dance and Music’. It reopened in 2016 as a mix of offices, music studios, a hotel, a revolving restaurant and an observation deck with Europe's highest swing. Development of the area is set to continue until at least 2026.

“With the other buildings along the waterfront, there was a clear and quite persistent attempt by the authorities in Amsterdam to create enough of an attraction, so the river stopped being a barrier between the city itself and the northern areas. The Dutch are quite successful in doing that – they are very pragmatic in it,” says Dr Esra Kurul, professor of organisational studies in the built environment at Oxford Brookes University.

A'DAM LOOKOUT

Amsterdam-Noord

“The redevelopment of this part of town has opened and enlarged the city of Amsterdam” Sandra den Hamer, EYE Filmmuseum

Inside the EYE, subtle changes have happened with the staff canteen doubling as a banquet or workshop room, and office space given back to the public. But, says den Hamer, if she were to change one thing about the building, it would be to make a window or entrance at the back.

“The back side is facing the neighbourhood and the front side is looking towards the central city – Amsterdam-Noord can only see the back of the museum.”

It is a minor detail in the overall accomplishment of getting the building constructed.

When asked about the EYE’s legacy, Feistel says it is its beauty: “The whole area changed completely. The building started the development, and this forgotten part of Amsterdam is now really part of the city. That is incredibly beautiful for us.”

Aerial view over Amsterdam. Photo by Iwan Baan