Two years ago, Allianz, the world’s largest insurance company made a $1bn bet on build to rent (BTR). The company headquarters is in Germany, but the investment was in Japan. Today, additional investments have increased the total pot to $1.5bn, and the insurer is the proud owner of roughly 5,500 rental homes.

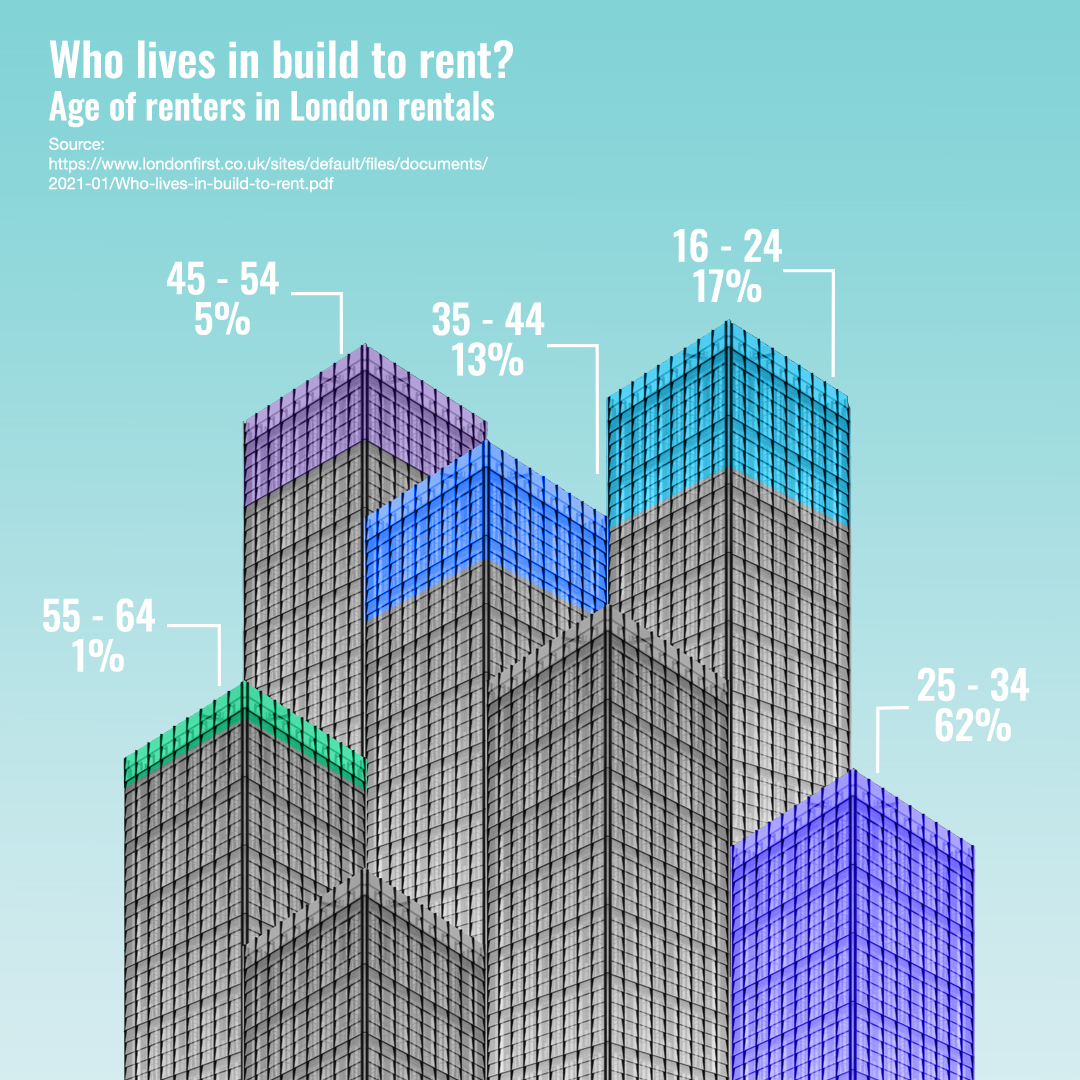

The Allianz case is no isolated example. Around the world investors are flocking to the sector. Also known as private rental or – in Asia and North America ‘multi-family’ – BTR provides well-heeled young professionals, who are typically single and between 25 and 40, with desirable rental homes.

Developments are concentrated among the world’s leading cities, where years of rising house prices have put home ownership beyond the reach of many. Renters settle for smaller living spaces in exchange for hotel-style facilities – glamorous communal areas, co-working spaces, communal dining room, gyms and the like. Developers can carve more flats out of the same amount of space, increasing their margins and the long-term rental yields for investors like Allianz.

But the model poses challenges. Communal living needs careful management and a close eye on costs, as the major property companies operating BTR developments are learning fast. COVID-19 has hit the sector: released from the need to be close to the office and seeking more space in which to work from home, the pandemic has seen renters abandon small spaces in central city locations. And with years of rising rents forcing locals out of central city neighbourhoods, BTR faces the looming threat of rent controls. Can it ride the early rush of investor interest to establish itself as a genuine alternative to build to sell for investors, operators and tenants?

Sudden growth

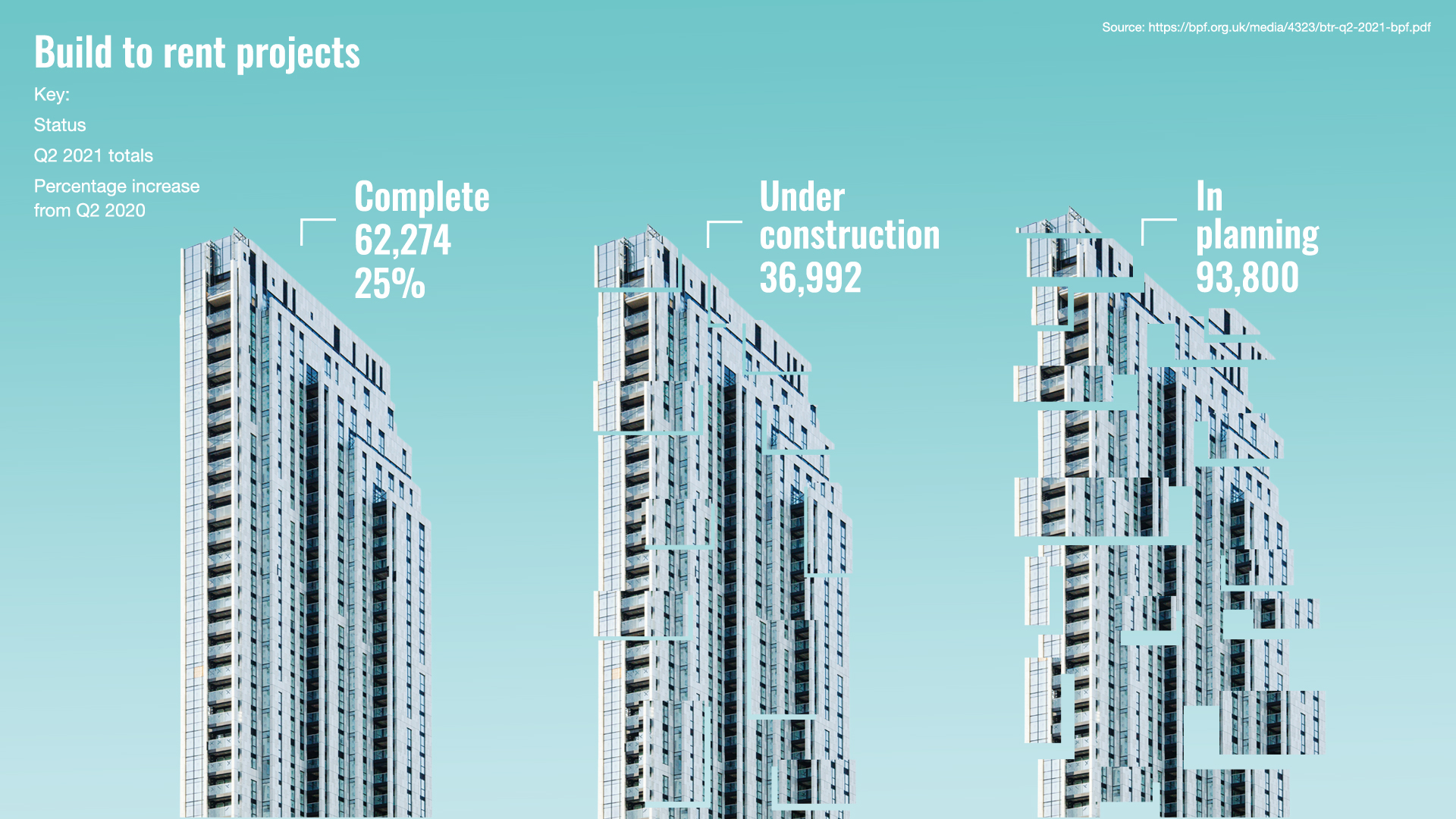

No one can doubt the investment boom in the sector. In the first half of this year, global investors allocated roughly $133bn to the sector, the largest amount of any equivalent period to date. That’s nearly a fifth up on the same period in 2019 before the pandemic struck, according to Real Capital Analytics. In the UK, the 6,937 new BTR homes securing planning permission in the first three months of 2021 was a quarterly record. Over the same period, £1.2bn flowed into the sector, the highest first quarter of any year in history, according to Savills.

“The rental market works off tighter living quarters, with more communal living areas,” says Tony Loughran MRICS, head of Cushman & Wakefield’s valuation and advisory team in Madrid, Spain. The model is crucial to BTR’s financial appeal because it allows developers to squeeze a higher rent per square metre out of the same space. But cramped living spaces are poorly suited for working from home. And the appeal of central city locations has faded as workers are needed less or never at the office.

Seeking larger homes with outdoor space in which to weather lockdowns and support home working, many renters have left city centres (where BTR properties are concentrated) for the suburbs, satellite towns or rural locations. Meanwhile, with many communal spaces and other facilities off-limits for much of the last 18 months thanks to social distancing requirements, one of the key attractions has been missing.

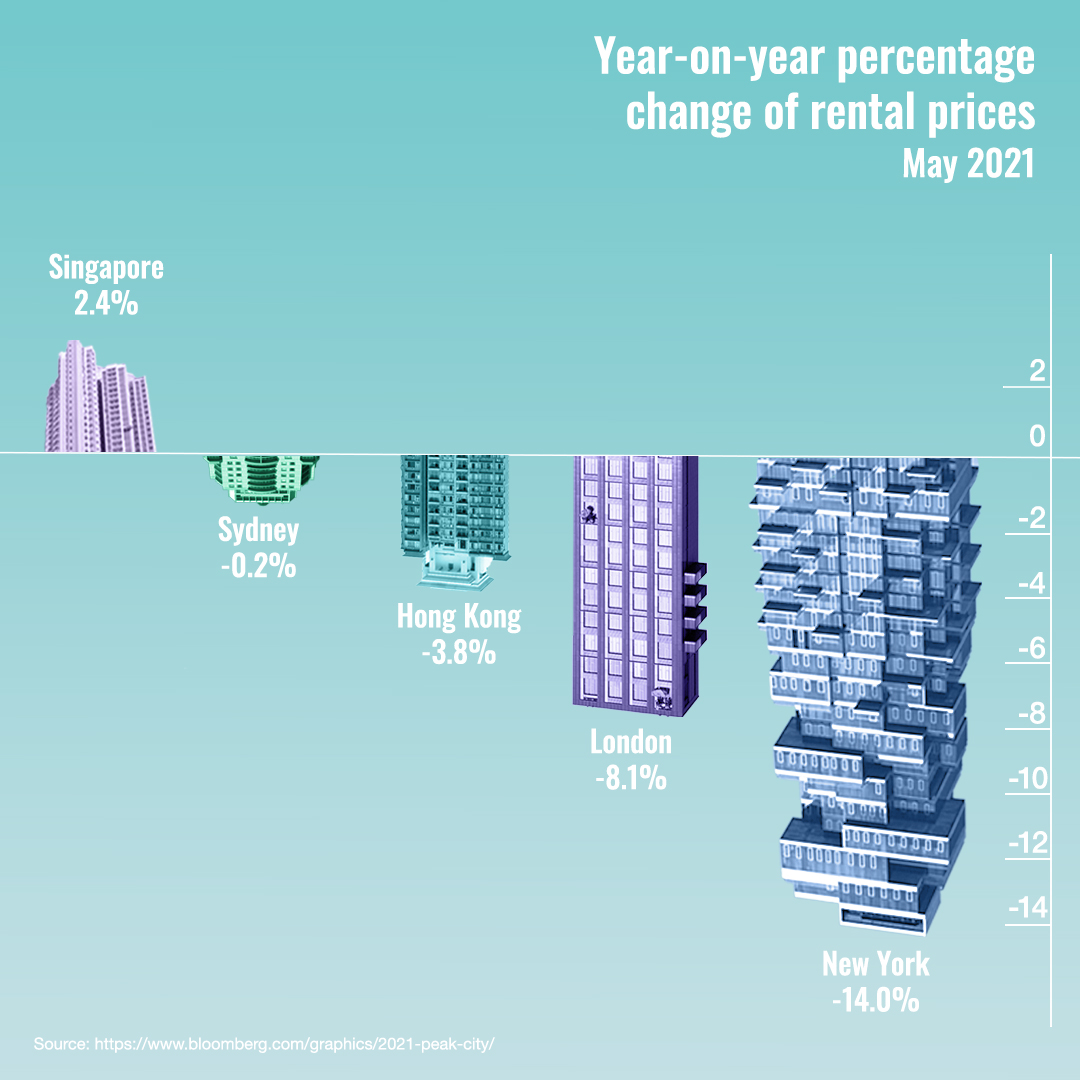

“Many renters have gone home to mum and dad,” says Sara Wilkinson FRICS, professor of sustainable property at the University of Technology Sydney. As prices have fallen across city rental sectors, BTR developers have had to cut prices to fill their buildings.

“Landlords have been trying to maintain occupancy by dropping rents by as much as 20% to 30%”, says Loughran. “Migrants haven’t arrived and neither have international students. The result in Sydney is that some landlords have buildings that are 50% occupied and are accepting 50% rent,” says Wilkinson.

Average price falls are hard to come by, but general rental prices give a guide. A year after the first lockdowns came in in March 2020, the average rental price for a one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco had fallen 45%; in New York one-beds were 27% cheaper. Inner London rents in the year to January fell 16%, according to Hamptons.

Planning for the long-term

Investors are looking past the sector’s pandemic woes to the long-term future of city rental markets. In Asia, the trend to urbanisation is continuing in large economies like China and Japan. Combined with growing affluence and runaway property sale prices, it is increasing demand for residents seeking well located rental homes with attractive facilities.

“[Asia has] excellent urban economic growth profiles and a shortage of high-quality housing, particularly purpose built,” says Stuart Mercier, head of Asia at Brookfield Asset Management, one of the world’s largest property investment managers.

In China, the government, wary of the social effects of waning housing affordability, has increased the supply of land available to BTR developers, establishing special funds for the purpose and even engaging directly in construction.

“BTR is a key component of China's long-term real estate strategy,” says James Shepherd MRICS, head of business development services, Greater China, at Cushman & Wakefield.

“It is not limited to cities with high or rapidly growing housing prices. Small and medium-sized cities with lower net population inflows have also demonstrated demand for affordable rental housing.”

Japan’s market is particularly well suited for investors in BTR, says Hideaki Suzuki FRICS, head of research and consulting, Japan, at Cushman and Wakefield in Tokyo. “It is one of a few markets in Asia Pacific that offers a great amount of multi-family investable stock and [where] risks are considered limited with low rent delinquency rates,” he says, adding that a range of sophisticated operators offering asset management services for multi-family are also present.

These benefits are compounded by the attractive investment characteristics for insurance companies like Allianz. Years of low interest rates, which have driven down the returns available from government and corporate bonds, have made investors desperate for the type of secure long-term income provided by BTR.

“Long-term trends – including a growing young population, a lack of affordable housing, and urbanisation – have bolstered demand for this asset class,” says Danny Phuan, head of acquisitions, Asia Pacific at Allianz Real Estate, the firm that manages Allianz’ $1.5bn Japanese investment.

Best of a bad bunch

Recent rent cuts and vacancies in the BTR sector compare well to the stark fall in use of offices and retail units. In May, rent collection ranged from 92% to 98% in the UK, thanks to savvy management, according to a recent report by CBRE. “Operators reacted swiftly [to COVID-19] establishing hardship processes and worked closely with tenants,” noted the report. It pointed to rent deferments, incentives on renewals and new lettings and rebates to renters when communal facilities closed to keep tenants happy.

“Our existing BTR portfolio in Japan has performed well despite the COVID-19 pandemic, validating our conviction about the resilience of this asset class,” says Phuan.

The sector is relatively protected from the pandemic’s long-term economic fallout. This has left lower wage workers – particularly prevalent in sectors like retail and hospitality, which have borne the brunt of the economic damage – harder hit than the affluent young professionals working in sectors like professional and financial services or technology.

By December 2020, 42% of those on low incomes in the US said they were in a worse financial situation than a year earlier, compared with just 22% on high incomes, according to a global survey by Morning Consult Economic Intelligence. In Italy the proportions were 42% and 12%; in Germany 32% and 17%; in in Brazil 40 and 26%.

A year after the first lockdowns came in in March 2020, the average rental price for a one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco had fallen 45%.

Diversifying

Build to rent also appeals to developers seeking to diversify their portfolios at a time where building homes to sell has become more complicated in some cities.

Australia is one of several countries that has increased purchase taxes for investor buyers to tame price inflation and protect stock for local workers. For the developers that relied on investor pre-sales for financing, this has created an obstacle. “In Australia, developing apartments to sell has got harder,” says Paul Winstanley FRICS, head of build to rent, Australia and New Zealand for JLL. “Banks won’t fund developers unless they have pre-sales, so building big blocks of apartments has become more difficult. In addition, construction costs and land prices have gone up.” He points to other benefits of the BTR model such as selling a single building in one transaction rather than 400 individual flats.

But the BTR sector is not immune from concerns about affordable housing. And developers must face the uncertainty of rent regulations as part of their due diligence.

“Local authorities want to be seen to be creating housing. Rent control is going on at a micro level in certain cities and markets. This adds an extra layer of complexity,” says Loughran of the sector in Spain. In some cases, local rent control laws change between an apartment being approved and when it is built.

A different kind of market

As investors like Allianz grow their BTR portfolios, they are looking to the major property companies like CBRE, JLL, Cushman & Wakefield and Colliers to manage them. These companies are scrambling to get familiar with a sector that has little in common with the offices, retail units or logistics facilities they are used to.

Many existing BTR operators are small scale, with low overheads. Matching their low fees while producing the high standards expected of the investors is challenging, says Loughran. “Management in this sector is very mom and pop – often self-employed and charge low fees using an infrastructure that already exists.”

For office, retail or logistics properties tenants are used to paying for rent, service charge and property tax separately. “But residential tenants want to pay a single all-inclusive rent. There is a lot of leakage from running costs and operating expenditure.”

Developing knowledge and skills in the new sector is frustrated by BTR’s fragmented nature. Unlike the commercial office buildings, where running one in New York is much like running one in London or Hong Kong, the BTR market is effectively hundreds of micro markets in different countries, dominated by local managers, local agents and local marketing requirements.

“In Japan developments are often smaller-scale with smaller apartments, the focus is on providing tenants with somewhere to live,” says Winstanley. Here resident amenities may be limited and the focus is on the providing the basic essentials at the right price. By contrast renters paying higher prices in central Melbourne or London will expect extensive communal facilities and a high level of management, he notes.

“The institutional money wants us to do as much as possible [to create] cost efficiencies. It is hard to get those efficiencies through economies of scale when each residential market is its own micro market with local demand drivers and local service companies (agents and managers),” says Loughran, who doubts that the sector will see the same domination by a small number of the global firms like the office market has.

"It is hard to get cost efficiencies through economies of scale when each residential market is its own micro market.” Tony Loughran MRICS, Cushman & Wakefield

Energy efficiency

One way to keep costs down is to make buildings more energy efficient, a trend which squares with institutional investors’ keen eye for the environmental, social and governance (ESG) credentials of buildings in their portfolios.

When it comes to building, the embodied carbon of a development must be considered alongside the social impact of providing homes in cities where people want to live and housing affordability is a concern. “Refurbing is often more environmentally sustainable because of the embodied carbon, assuming there are no harmful materials in the original construction. However, density may be an issue. Higher density [buildings] are now permissible in some locations so knock down and rebuild may enable you to house more people and so you can argue higher social sustainability,” says Wilkinson.

With many BTR developments on the edge of cities built on brownfield sites, investors can influence the embodied carbon in the building process and ensure they are carefully designed. But in central locations where second-hand buildings are more common, increasing energy efficiency can be challenging.

In Barcelona, Cushman & Wakefield is currently advising on the conversion of an old warehouse to rental homes. Among the local authority’s restoration requirements is that the original wooden trusses be retained. These were built to carry only single glazing in the sky lights, so the solution will be to incorporate light-weight double glazing at greater cost to achieve the Category A energy rating desired by the [investor] fund, Loughran explains.

Fast forward

Back at Allianz Real Estate, the team is busy calculating the environmental footprint of its fast-growing BTR portfolio, part of a two-year audit of the 550 or so property developments that it owns across a €74bn property portfolio.

Even in Japan, one of Asia’s most developed real estate markets, finding accurate information about a BTR building’s carbon emissions is hard. “Real estate is not yet a commercial asset class there so [carbon] toolboxes are still focused on commercial buildings,” says Dr Raphael Mertens, chief risk officer and head of ESG across Allianz Real Estate, which manages Allianz property investments.

But that will not delay things. Mertens has set a deadline of the end of next year to turn around poor performing buildings. This will add another task to a lengthening list for professionals like Loughton. With investors like Allianz calling the shots, expect BTR to keep changing fast.

Get Modus features sent straight to your inbox by signing up for the newsletter.