Photography by Peter Landers

Sitting majestically in the garden at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire is the Cascade, an extraordinary 327-year-old stone water feature.

With 24 steps descending for 60m, water streams down in a design that mimics a natural waterfall. The Cascade is a feat of engineering and an early example of sustainability. It uses the natural water flow of the landscape to create a piece of historic land art that helps power water systems across the Chatsworth Estate.

To its 600,000 annual visitors it is simply a well-loved feature, a place where families picnic peacefully while children paddle among its steps, each one a different size and shape to vary the sound and the flow of the water. But underneath these paddling feet, the Cascade is struggling. It is leaking and is badly in need of structural repairs and restoration, highlighting the never-ending story and pressures of conservation at one of England’s most treasured stately homes.

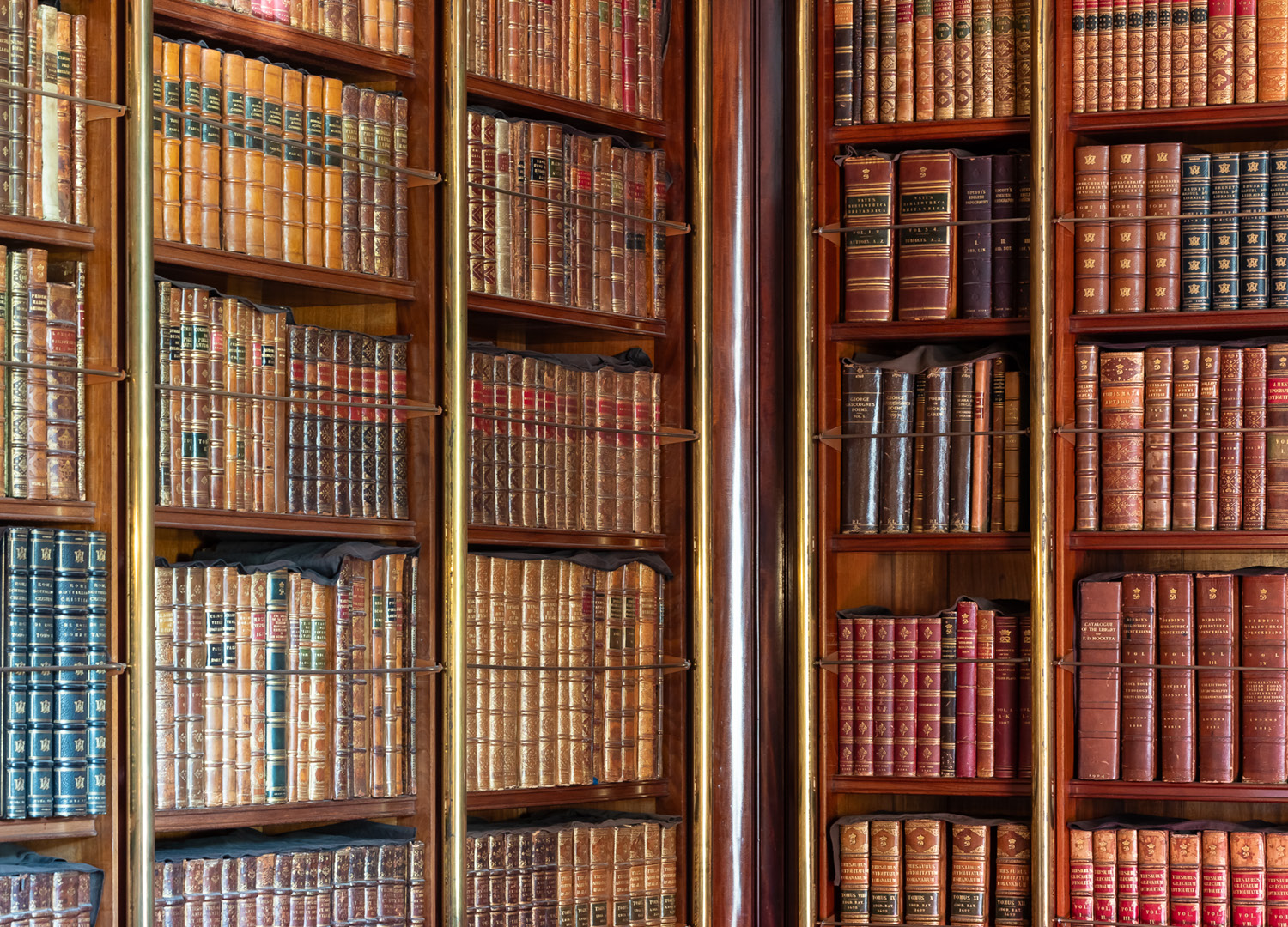

Chatsworth House has an illustrious history. Originally built in 1552 it has been the home of the Cavendish family for 17 generations and has seen extensive redesigns, additions and remodelling over the centuries. Today the house is Grade I listed, the highest level of architectural and historic interest in England. It sits among 1,822-acres of parkland and includes 105-acres of garden as well as 48 other listed buildings, nine of which are also Grade I.

Conserving and maintaining the house, garden and park is the priority of the Chatsworth House Trust, the charity set up by the Cavendish family in 1981. But conservation is perpetual and keeping Chatsworth up to its high standards has multiple challenges. It is, says Robert Harrison MRICS, Chatsworth’s head of operations, a fine balancing act.

The trust estimates that it would cost £30m to preserve everything on the estate. But once operating costs have been removed it’s generally left with between £1m and £2m a year to reinvest. The cost of the Cascade project alone has been estimated at £7m. “That £30m figure is only going to increase,” says Harrison. “The longer we take fundraising, or not generating more income, the distance between those two numbers gets bigger because the buildings continue to deteriorate.”

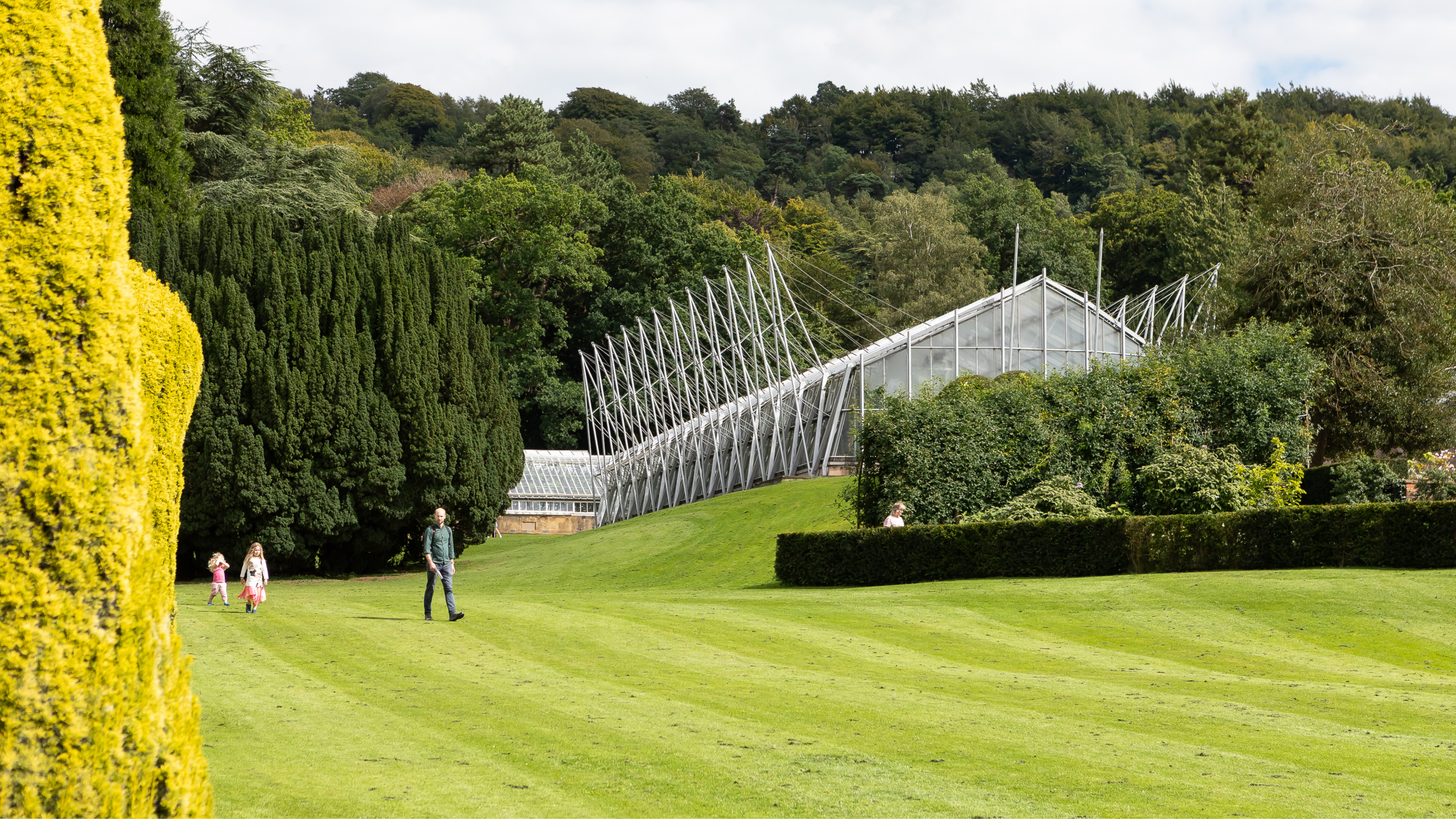

The maze and greenhouse are some of the focal points of the gardens.

Within Paxton's Glasshouse grows the Cavendish Banana (above), which most of the bananas we eat today are descended from.

Top priorities

The Cascade has been identified as a priority project and will be restored over the next four to five years. The original Cascade was completed in 1696 by a French hydraulics engineer, Monsieur Grillet, who had worked for Louis XIV. Over the centuries the design was significantly modified, almost doubling in length. In 1830 a tunnel was built underneath to transport coal to the Great Conservatory, as the then Duke didn’t want to see workers moving coal through the gardens, and this significantly weakened its structure.

Harrison says the last restoration work was completed in the early 1990s. “We're aware now that we’ve got to take the entire Cascade up stone by stone, very methodically, very carefully,” he says. “We've got to restore it, we've got to re-waterproof it to stop the water running out of it, but actually walk away from it looking exactly the same as it was before.”

The length of the Cascade is longer than the length of the house itself.

Sarah Owen and Robert Harrison. Photo by Jasper Fry

“We’ve got to take the entire Cascade up stone by stone, very methodically, very carefully” Robert Harrison MRICS Chatsworth House

This process will not be easy. The Cascade is part of a complex waterworks system that utilises Chatsworth’s natural hilly landscape to collect water from the moors into man-made lakes. These feed down into the garden’s water features, into toilets and finally a water turbine, which provides electricity for the house. This is just one of Chatsworth’s sustainability systems, which also includes biomass boilers and heat pumps, that have contributed to a 32% drop in emissions across the estate since 2015. Harrison says he expects to get a full project plan for the Cascade in place next year and the full listed building consent submitted by late 2024. The next 12 months will be a real "pinnacle point", he adds.

So far, the trust has been awarded £422,000 from the National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF), to finance initial research and exploratory work, plus an accompanying education and public engagement project. It will apply for a further £4.5m from the NLHF for its delivery phase but will be left with an estimated £2.5m shortfall. “The public support around that will be crucial,” says Sarah Owen, Chatsworth’s director of development, who will oversee the project. “It is a great sustainability story for us, and once spades are in the ground that gives us a huge opportunity to talk about what we’re doing here in terms of water and the green agenda.”

“We need to be a bit more front and centre telling people about the needs we have and how they can support us in doing that” Sarah Owen, Chatsworth House

(Above) Robert Harrison in the workshop with his team fixing a window.

Conserving the clock tower

The Cascade is not the only conservation project at Chatsworth. This winter the trust will start a 12-month restoration on its stables clock tower. Built in 1767, the working clock tower is in a focal position on the estate, with shops and restaurants surrounding it.

Harrison says the tower needs significant structural repairs from the bottom right to the cupola at the top. He adds that due to its popularity with visitors, the work will have a “massive operational impact”. The trust is also working on restoring its Elizabethan Wall, a 16th century stone retaining wall in the garden, which has huge historical significance. Rather like the Cascade, the restoration will take years and will be done painstakingly in sections, following strict heritage guidance.

As these projects converge, Owen says it allows them to tell multiple stories about the work of the Chatsworth House Trust. Not just to engage its visitors in its history, but to educate about its sustainability story, and perhaps most importantly for Owen and Harrison, to raise additional funds to complete the projects. “People come to Chatsworth and it looks absolutely extraordinary,” explains Owen. “We need to be a bit more front and centre telling people about the needs we have and how they can support us in doing that.”

“There’s no better way of getting to know a building than to actually draw it, measure it and survey it yourself” David Humphreys FRICS, Architectural Conservation Professionals

The kitchen gardens grow seasonal produce used in the estate's restaurants.

The Hunting Tower is now a holiday rental.

The aqueduct is another feature needing conservation work.

Queen Mary's Bower was used as a raised exercise ground when she was held as a prisoner at Chatsworth.

The secrets a building may hold

“If you’re sensitive and patient enough then the building will communicate to you,’ says David Humphreys FRICS, group director of Ireland-based Architectural Conservation Professionals.

Humphreys has a long career as a surveyor restoring historic buildings both in his native Ireland and in the UK and Australia, as well as being a trained blacksmith. His sense of anticipation of what a building may hold and his strong sense of purpose in restoring historic buildings, mirrors that of Chatsworth’s Robert Harrison.

“There’s a sense of excitement, like a new Sherlock Holmes mystery,” he says. “It’s the excitement of what you may find, a new mystery that’s got all its challenges.” He adds that in any project, he’s there to represent the building, it is the building that is his client. This enables him to remain neutral among the planning, conservation and development stakeholders.

“I’m there speaking for the building because my objective is to protect the building,” he says. He adds that it’s vital to understand historic buildings and says the best way is to “spend time with them”.

“There’s no better way of getting to know a building than to actually draw it, measure it and survey it yourself.” He adds that once a building has been repaired and restored, it can be left to “tell its own story.”