Memorials are a central part of many countries’ remembrance and commemoration cultures. The creation of monuments, sculptures and memorial spaces provide tangible tributes that link the past to the future, allowing us to remember those gone before, while offering vital lessons for the present.

Memorials, such as the Cenotaph in London, the 9/11 Memorial in New York or even the Taj Mahal in India become landmarks, not just in the built environment, but in a country’s national psyche.

But as the world changes, our view of the past and the future is shifting and, with it, the way we commemorate - leading many to question the relevance and even appropriateness of some of our past memorials.

Throughout history memorials have been used as a way of honouring and remembering the dead as well as expressing collective grief. One of the oldest war memorials is believed to be the White Monument in Syria, a huge mass burial mound for the battle dead dating from the third millennium BCE, more than 4,000 years ago. Archaeologists believe that the construction of the monument, visible in the landscape for miles around, would have also served as a message to nearby communities.

Judith Dupré, author of Monuments: America’s History in Art and Memory, believes the purpose of memorials is to help the “disenfranchised” move forward. “More important than the monument that is finally built is the work that proceeds it,” she says. “Finding a memorial’s most appropriate expression is a necessary psychological process that helps people work through issues, allowing resolution and healing. You could say that the monument we see is the tip of the commemorative iceberg.”

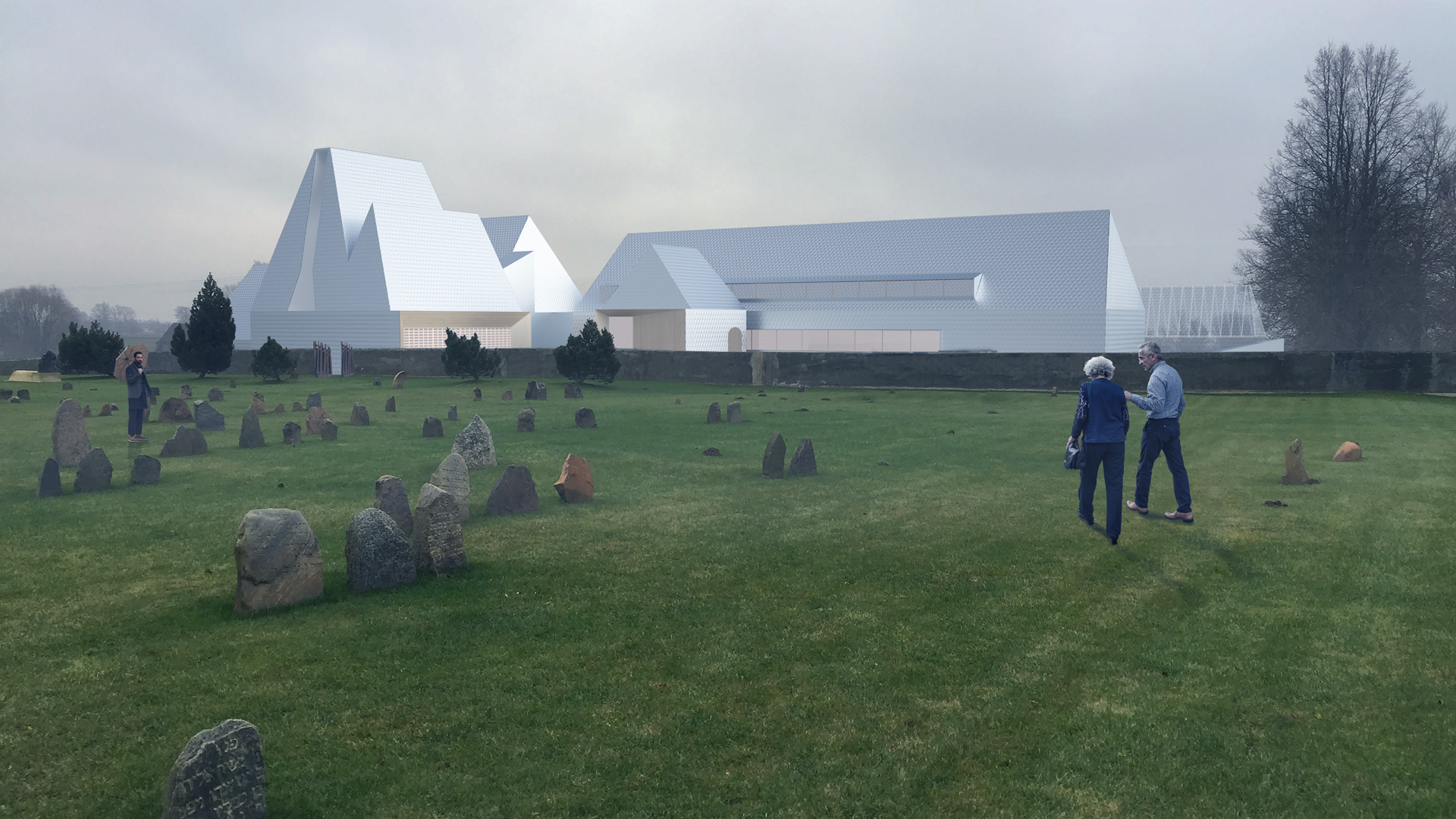

The Lost Shtetl Museum in Lithuania, due to open in 2024, illustrates this point. But it is also an example of the various forms memorials can take and the different messages they can convey. The museum is located in Šeduva, in the north of the country, once home to a Jewish shtetl (Yiddish for small town or village). It is a memorial to a way of life that was entirely wiped out in Lithuania during the Second World War when 90 per cent of its 250,000 Jewish population were murdered during the Holocaust.

The project began back in 2014 and is funded by sponsors with connections to the area, with a Finnish design architect, Lithuanian engineers and New York-based exhibition designers. David Duffy FRICS, founder of Zurich-based Ecas AG and project manager of the museum building, says its design, floorplan and the exhibition will all tell a story which will be both experiential and immersive.

“The main part of the story the sponsors are telling really only starts when you get to the three-storey Holocaust gallery,” he says. “For those of us who have been working on it for six years, it really gets to you, no doubt about it.”

The museum is located near three of the sites of mass killings of the shtetl’s residents, its location holding poignant resonance. Inside a wall with 297 amber coloured glass panes provides a “simple monument” to all the lost Jewish shtetls across the Baltics.

The country’s prime minister, Ingrida Šimonytė, has been highly supportive of the museum as a way of the Lithuanian people coming to terms with their part in the Holocaust. But as many countries continue national commemorative traditions, such as laying poppy wreaths on war memorials for Armistice Day, there has also been a shift in the way people collectively choose to remember and who they want to memorialise.

In her book, Dupré points to an “early harbinger of the revolution in memorial design” with the AIDS quilt in the US. Started in 1987 the quilt was designed to honour those dying from the AIDS virus in San Francisco and provide solace for those grieving them. That year it was displayed on the National Mall in Washington DC and covered a space larger than a football field. By 1996 it covered the entire National Mall. Today it’s a 50-tonne tapestry that commemorates 110,000 people who died of AIDS and is available as a permanent and searchable online memorial.

Now, Dupré says there is a wider spectrum of commemorative practices. “In the 19th and early 20th century, neoclassical monuments were built by the elite for the elite. These civic commemorations stood for the collective grief of a nation and were never meant to provide individual solace. Now we're seeing a shift to very personal expressions of commemoration that may have meaning only to one person.”

This includes more “spontaneous memorials” where people might leave flowers or maintain a vigil at a site where someone has died, as seen recently in the UK after the death of Queen Elizabeth II. Part of this shift, Dupré feels, is fuelled by social media - people wanting to play a part in the memorial and “asserting their individuality”.

Social media also played an enormous role in the Black Lives Matter protests which reverberated around the world in 2020. For countries with colonial pasts, it prompted a collective historical re-think, particularly around figures with links to the slave trade who had been venerated with monuments and memorial statues.

“Finding a memorial’s most appropriate expression is a necessary psychological process that helps people work through issues, allowing resolution and healing” Judith Dupré, author of Monuments: America’s History in Art and Memory

1012 N. Main Street, Fort Worth, Texas. Photo by Daniel Banks, courtesy of Transform 1012 N. Main Street.

Fred Rouse Center

The beauty of memorials is that they have so many different forms. For the Fred Rouse Center in Fort Worth, Texas, the reimagining of a space once used for division is a beautiful memorial to a victim of racism.

In 1921 Fred Rouse, a black man employed as a butcher during a strike, was murdered by a mob of racist strike agitators in the city. The US white supremist group the Ku Klux Klan had a major presence in Fort Worth at that time, with its headquarters on Main Street designed to fit 2,000 people.

Fast forward to 2022 and the building was saved from demolition by a coalition representing groups once targeted by the Klan. It has been renamed the Fred Rouse Center and includes one of Fred’s descendants on the board. It will include performance and exhibition spaces dedicated to social justice and civil rights and provide work studios for local artists in residence.

In the US, groups removed and defaced memorials of confederate leaders and those emblematic of white supremacy. In the UK, more than 70 memorials of slave traders and colonialists were taken down while the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, set up a commission to review the city’s memorials and statues and find ways to reflect its diverse history, saying: “We must ensure that we celebrate the achievements and diversity of all in our city, and that we commemorate those who have made London what it is – that includes questioning which legacies are being celebrated.”

In May, 42 community groups in London were given grants to create new memorials including rainbow plaques celebrating LGBTQ+ history and murals depicting influential black women chosen by local people. Dupré maintains that it is simplistic to think that racial and social injustice can be solved just by demolishing or erasing monuments. Instead, she believes we should be amending memorials with teaching plaques or creating interpretative parks or museums where their historical context is made clear.

“A dialogue is taking place now that has never taken place before,” she says. “Traditional monuments uphold a singular national narrative. Now we're saying, wait a minute, there are all kinds of voices, women, minorities, the voices of people who were very much involved in those events, a part of that history that has been ignored.”