Somewhere, deep beneath the calm suburban streets of Stockholm, lurks a 1,000-tonne monster.

A ravenous, 240-metre-long tunnel boring machine (TBM) is rapidly eating its way through the rock that underpins the Swedish capital. Its name is Elektra and it is part of a $1.4bn project to dig an eight-mile tunnel.

Stockholm is one of Europe’s fastest-growing cities, its regional population having soared from 1.2m in 2000 to 1.74m by the end of 2024. As a consequence, the state-owned electrical transmission company, Svenska Kraftnät AB, has decided to increase capacity for the city’s electric grid to account for future population increases and to meet the country’s decarbonisation requirements. Sweden’s plan is to be carbon neutral by 2045, with Stockholm aiming to be fossil-fuel free by 2040.

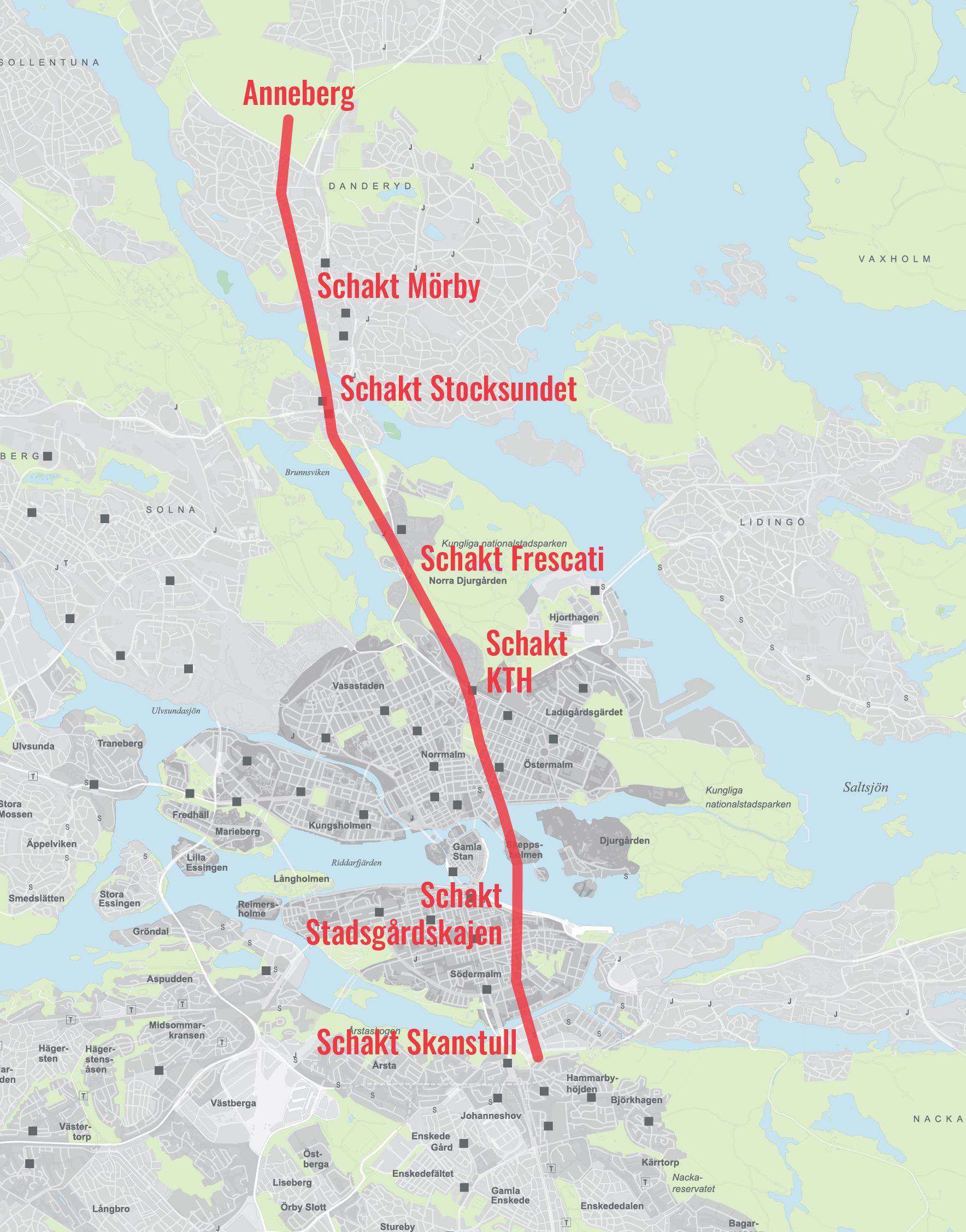

The result is the ambitious Anneberg–Skanstull tunnel, which runs up to 100m underground (the deepest sections of the London Underground and New York subway are only about 60m down). It will, when it is complete in 2028, house nine cables and increase Stockholm’s electrical capacity from 3.5GW to 6.5GW. It will also be able to hook up to the windfarms planned – but not currently passed – for the Baltic Sea.

Meanwhile, the tunnelling continues. Elektra, on average, can bore its way through 70m of rock face a week. It works by gripping the tunnel sides with the body of its machine and extending its rotating drill head forward. The head itself is five metres wide and has 28 cutters each weighing 200kg. During operation (which is limited to daytime to minimise disturbance for residents), the whole section of tunnel vibrates, creating 100dB of noise.

Map of the tunnel route from Anneberg to Schakt Skanstull

The entrance to the Anneberg-Skanstull Cable Tunnel, operated by national grid operator Svenska Kraftnat AB. Photographer: Erika Gerdemark/Bloomberg

Workers on the Elektra boring machine as it drills the Anneberg-Skanstull Cable Tunnel. Photographer: Erika Gerdemark/Bloomberg

The machine stops after a 15-metre section has been completed and the walls are sealed with grout to prevent water ingress – Stockholm is, famously, built on an archipelago. While the walls dry, trial holes are drilled in the next section to assess the rock and any potential hazards before work begins again. It is one of the first projects to be undertaken this way in Sweden, the country that invented dynamite.

The project has been ongoing for more than four years and, when the tunnel has been fully drilled, will take at least another three years to fit out. Such is Elektra’s consumption of power that, on very cold days, it has had to rest completely to allow for the extra heating needs across the city.

While it bores its way through Stockholm’s substrata, Elektra produces 20m3 or about 10 lorryloads of spoil each day. As befits a project that is part of plan to clean the environment, once removed, the debris is repurposed for industrial use.

The ability to contribute to a circular economy and raise the sustainability credentials of a tunnelling project in this way isn’t always possible though, says Mike Kenyon MRICS, head of plant and machinery at Cushman and Wakefield.

“Depending on where the boring machine is located makes a difference as to whether the spoil can be reused for other projects,” he says. “Mud, sand or clay could be used in road constructions or even to establish the road foundation for the present boring.”

Giant drills – and the projects they are being used for

A tunnel boring machine drilling through rock

The Anneberg–Skanstull tunnel is an impressive example of a giant infrastructure project that is supporting decarbonisation. But, despite its size, Elektra is not the biggest of the TBMs.

The first successful modern TBMs were invented in the 1950s and as the technology has improved, they have become the tunnelling method of choice for a variety of ground conditions. The key factor in this technological leap forward was “its speed and efficient removal of spoil,” says Kenyon.

Here are some other notable TBMs and the projects they were built for:

Qin Liangyu

Used to bore an underwater crossing in Hong Kong, this German-designed TBM had a cutting head diameter of 17.6 metres and weighs 4,850 tonnes. The 5km tunnel took two years to drill out.

Bertha

A shade under the size of Qin Liangyu’s cutting head, at 17.45 metres, and costing $80m, in 2017 this Japanese machine was brought to Seattle for the construction of a 3.2km section of the city’s State Route 99.

Santa Lucia

Built by the same firm responsible for Qin Liangyu, but with a smaller diameter of 15.8 metres, this TBM was used to build the tunnel connecting Florence and Bologna in Italy, in 2015. At 7.5km, it is Europe’s longest road tunnel and this is the largest TBM used on the continent.