Illustrations by Hudson Christie

Global population growth and consumption rates are putting huge pressure on natural resources and construction is a key contributor, responsible for over a third of global resource consumption, according to figures from the OECD.

Given that about 50% of the urban environment needed by 2050 is not yet built, efforts to drive down the use of virgin materials and cut the volume of waste generated by construction and demolition will be critical in the years ahead.

Evidence suggests that a greater focus on waste materials reuse and recycling could result in major efficiencies. By applying circular economic principles to just five key products - cement, aluminium, steel, plastics, as well as food - the world could wipe out almost half the emissions from the production of goods, according to estimates by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. That’s 9.3bn tonnes of CO2 in 2050, equivalent to cutting all current transport emissions to zero.

Based on volume, construction and demolition waste is currently the largest waste stream in the EU. Recovery rates are generally high though, with most member states exceeding the EU’s Waste Directive target to extract value from at least 70% of materials either through recycling, re-use or material recovery, including backfilling operations.

Countries such as the Netherlands, Malta, Ireland, Iceland, Hungary, Italy and the UK all recovered close to 100% of construction and demolition waste in 2018, according to the latest available data. However, performance dropped off in other countries such as Cyprus (64%) and Norway (63%), with Slovakia (51%) and Bulgaria (21%) the worst performers.

Stephen Richardson, director of the Europe Regional Network of the World Green Building Council (WGBC) says: “There's a correlation between countries where the cost of tipping and sending things to landfill is pushed up through taxes and other mechanisms and where good progress has been made. For example, the UK’s high landfill taxes are a strong incentive for contractors to try and avoid waste.”

But even top-performing countries remain heavily reliant on waste recovery techniques (typically incineration to produce energy) and recycling, which sit at the bottom of the waste hierarchy, after disposal, and therefore are of limited benefit to the environment.

Recycling in construction is really a byword for ‘downcycling’, with materials mostly used in low grade applications that decrease the quality and value of the material. For example, inert material from demolition is mostly crushed and reused as aggregate in road construction, or embankments and foundations. Large amounts of timber are chipped up and either made into chipboard or burnt, rather being returned to production in a closed loop.

Katherine Adams, technical and research associate at the Alliance for Sustainable Building Products, who has more than 20 years’ experience in resource efficiency, points out that greater gains could be made. “Not much plasterboard goes back into plasterboard, instead it’s spread on land. Recycling glass back into glass can give major energy savings in production, but the majority is just crushed up as aggregate, because that’s the easier option. More questions are now being asked about why all this waste is being downcycled, can we not keep some of the value of it?”

There are pockets of recycling good practice, some product manufacturers offer “closed-loop” take-back schemes and work with contractors to return items such as carpets, ceiling tiles, lights or uPVC windows to factories at end of life. Main contractor BAM Construct UK is currently working with temporary protection materials company Protec on the Sky Studios Elstree project in London where boards containing over 60% recycled content will be taken back by the company at the end of the project to make more boards. “Typically, that type of product would be incinerated and all the value lost,” says Kris Karslake, sustainability manager at BAM Construct UK, who also chairs the Construction & Demolition waste group at the Chartered Institution of Wastes Management.

Steel is already a highly recycled material, due to its financial value, but working with Celsa Steel UK on a project in Port Talbot, Wales, BAM was able to optimise the benefits “Their recycled steel is only used in the UK and it’s a closed loop so you also get the benefit of lower emissions related to transport impacts,” says Karslake.

Increased awareness of embodied carbon and whole-life carbon is increasing interest in upcycling materials (converting existing materials into something of equal or greater value) and reuse to extend the lifespan of products. Both practices can help cut costs on projects by avoiding the need to purchase new products and cutting waste disposal costs.

Best practice examples of reuse include the Circl building in Amsterdam, part of the headquarters for ABN AMRO bank, where the basement walls are made from window frames from an old Philips building and the parquet floor is made from residual wood from other projects. In addition, the Resource Rows project In Copenhagen features bricks repurposed from local Carlsberg breweries and cut into modules to make new walls.

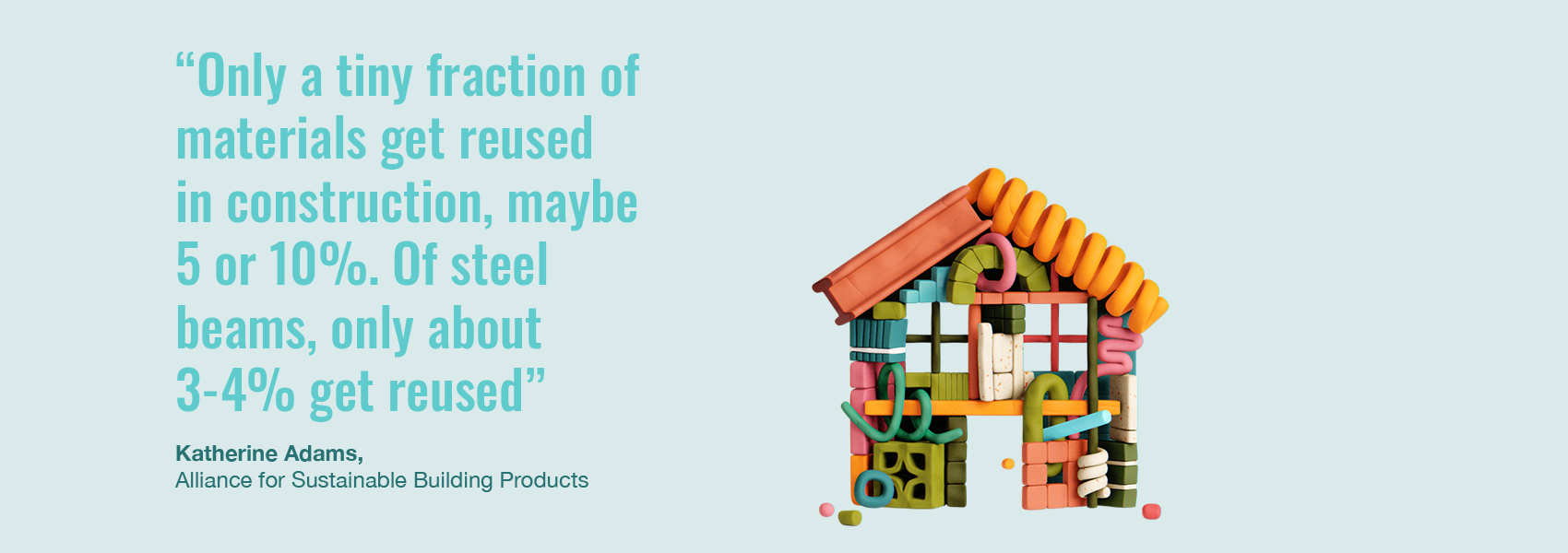

But the pursuit of circularity remains confined to just a handful of projects worldwide. “Only a tiny fraction of materials get reused in construction, maybe five or 10%,” says Adams. “Looking specifically at steel beams, only about 3-4% gets reused.”

Common hurdles to waste reuse and recycling include a lack of confidence in the quality of the products produced, which reduces demand and inhibits the development of appropriate waste management and recycling/reuse infrastructure.

Construction products in the EU typically require a CE mark, which is difficult for reused products to achieve. In some countries, it's illegal to use materials that haven't been through the same quality checks as regular products.

“You've also got to factor in the way the industry works,” says the WGBC’s Richardson. “Contractors tend to be relatively risk averse, so they'll stick to the materials and the products they know. If you're asking them to use unknown products, whether new or reused, that often comes with a cost uplift, simply to take on the additional risk. That means you need a client who's really got the vision for reuse and is willing to drive it forward and potentially take on more of that risk.”

If market dynamics, building regulations and corporate social responsibility targets aren’t enough to improve construction’s behaviour on waste, then perhaps new policy initiatives will catalyse change.

The UK government wants to eliminate all avoidable waste in England by 2050. A route map on how to achieve zero avoidable waste in construction was published last summer by the Construction Leadership Council and the Green Construction Board in collaboration with two government departments.

The strategy promotes refurbishment over demolition, cutting the amount of soil that goes to landfill, and designing buildings with end of life in mind. It estimates that 3.3m tonnes of CO2 could be saved each year by reusing construction materials currently treated as waste.

“Zero waste is by definition a challenging target,” says Andy Moores, director of research at the Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA), which provides good-practice guidance on waste reduction. “It requires innovative approaches, collaboration within and between sectors and a focus on sustainability, sometimes with an acknowledgement this may increase up-front costs, while emphasising that the whole life costs may reduce.”

A raft of legislative and non-legislative measures related to waste will come through the EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan. Implemented in stages over the coming years, the plan will, among other things promote measures to improve the durability and adaptability of built assets; consider a revision of regulated material recovery targets for construction and demolition waste and promote initiatives that increase the safe, sustainable and circular use of excavated soils. Furthermore, it will aim to ensure that the wave of green renovations announced in the European Green Deal will be implemented in line with circular economy principles, notably with optimised lifecycle performance and longer life expectancy.

However, Adams predicts that the measures specific to construction and demolition waste will not appear until 2025 at the earliest because the sector is viewed as a less of a priority and due to a lack of agreement on which products it should cover.

More economic support for projects, companies and products that pursue circularity is also expected to result from the new EU taxonomy, a green classification system that translates climate and environmental objectives into criteria for economic activities for investment. They will also motivate industries to think harder about their waste.

Construction’s waste footprint dwarfs all other sectors and its addiction to natural resources is a threat to the environment and biodiversity, so proactive policies like these may finally provide the key to cleaning up the planet.