In 1862 the eyes of the world were on London, one of the world’s most populous cities. Queen Victoria was in full mourning, the Industrial Revolution was in full throttle and the International Exposition, with 8,000 exhibitors from over 30 countries, was in full swing.

In other words, London was busy.

Referring to the 1861 Census, George Cruchley, cartographer and author, painted a vivid picture of life in inner London in his Handbook for Strangers.

“London contained a population of 2,803,034 souls, occupying 362,890 inhabited houses, formed into upwards of 10,500 streets, lanes and squares,” said Cruchley. “The increase of population in ten years was 440,798. The average of deaths is 1,300 weekly; of births, 1,800.

“To provide for so enormous an aggregate of men, women, and children, there are 30,000 bakers, 40,000 grocers, 24,000 tailors, 42,000 dressmakers and milliners, 29,000 bootmakers, and 170,000 cooks (professed - and plain), housemaids, valets, butlers, and other domestic servants.”

He continued: “13,000 cows supply milk and cream; 6,000,000 tons of coals feed the fires; nearly 400,000 gas lights, consuming every 24 hours 13,500,000 cubic feet of gas, at an average cost of 4s. 6d. per thousand, illumine the streets of London; 44,000,000 gallons of porter, 2,000,000 gallons of spirits, and 65,000 pipes of wine, are annually consumed; while to balance this surprising quantity of fluid, our purveyors slaughter for us 36,000 pigs, 29,000 calves, 250,000 oxen, and nearly 2,000,000 of sheep.

“Farmers, at home or abroad, furnish us with 1,600,000 quarters of wheat; our woods and preserves with 5,000,000 head of game; and our fishermen send us 3,000,000 salmon, and with such quantities of cod, and plaice, and soles, and herrings, that we dare not perplex our readers with their figures.”

Looking at maps of the London from 1862 offers a glimpse into how the city was run, and this map, found in the RICS archive, meticulously records the city's advancements in infrastructure while revealing some surprises. Here we pay special mention to some of the infrastructure feats of the day and highlight those that were yet to be built.

Tower Bridge

Albert Bridge

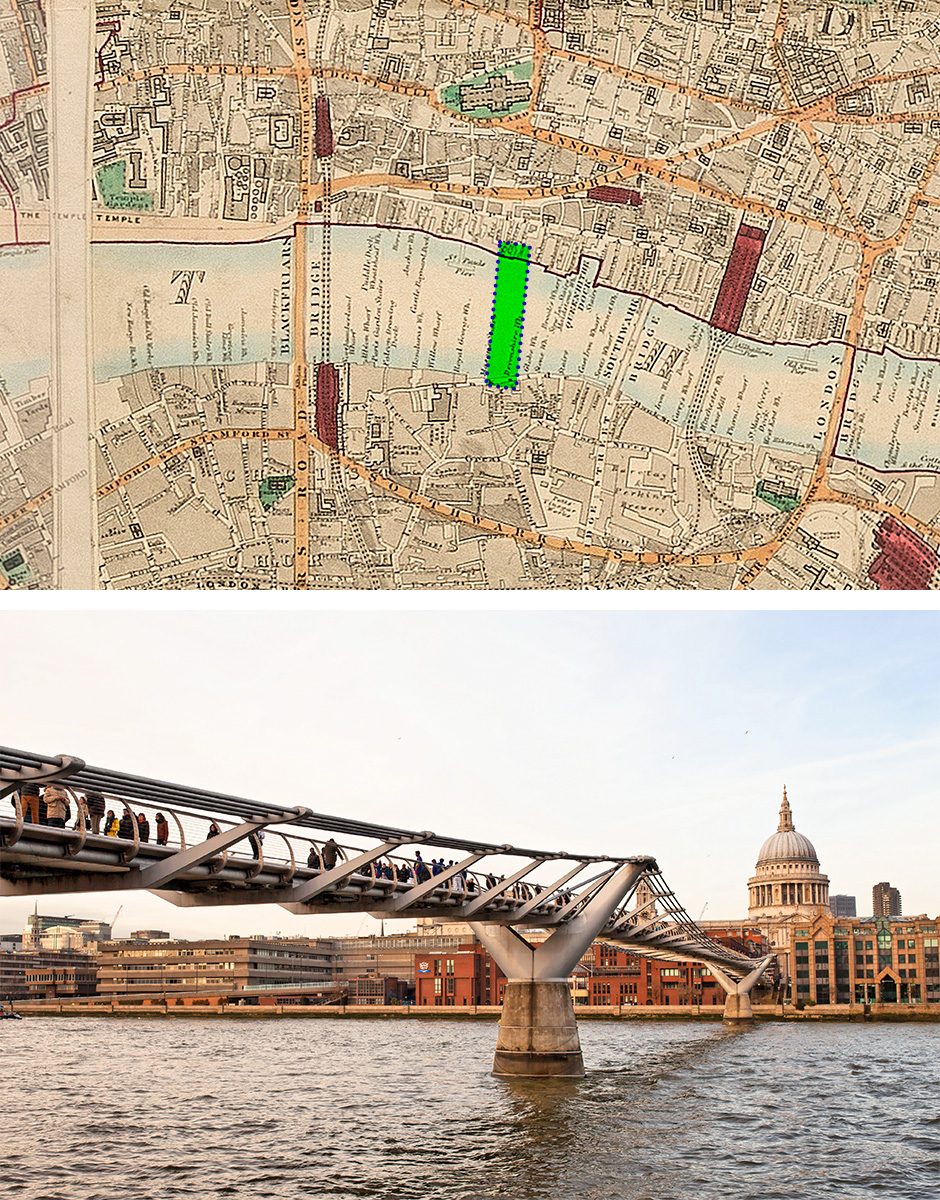

Millenium Bridge

Bridges

The current iteration of Westminster Bridge, connecting London’s south bank to the Houses of Parliament, opened in 1862, but looking at the map reveals some iconic London crossings are missing in that year.

Tower Bridge, London’s picture-perfect bascule bridge, opened in 1894 after an eight-year build. The high-level walkways, now a tourist attraction, were built so pedestrians could cross the river in safety. They were then closed in 1910 due to lack of use, with Londoners preferring to risk the road rather than the stairs.

Commissioned by Prince Albert and affectionately called the Trembling Lady due to its tendency to vibrate, Albert Bridge is one of London’s prettiest crossings. Construction started in 1870 with builders expecting the project to last one year and cost £70,000. Like many infrastructure ventures before and after, the estimates were off - Albert bridge took three years to complete at an impressive £200,000 (£28m in today’s money).

A more recent addition is the Millennium Bridge. Connecting the Tate Modern on Bankside to St Paul’s, the bridge was opened in 2000 but closed shortly after due to a severe case of the wobbles, eventually reopening in 2002.

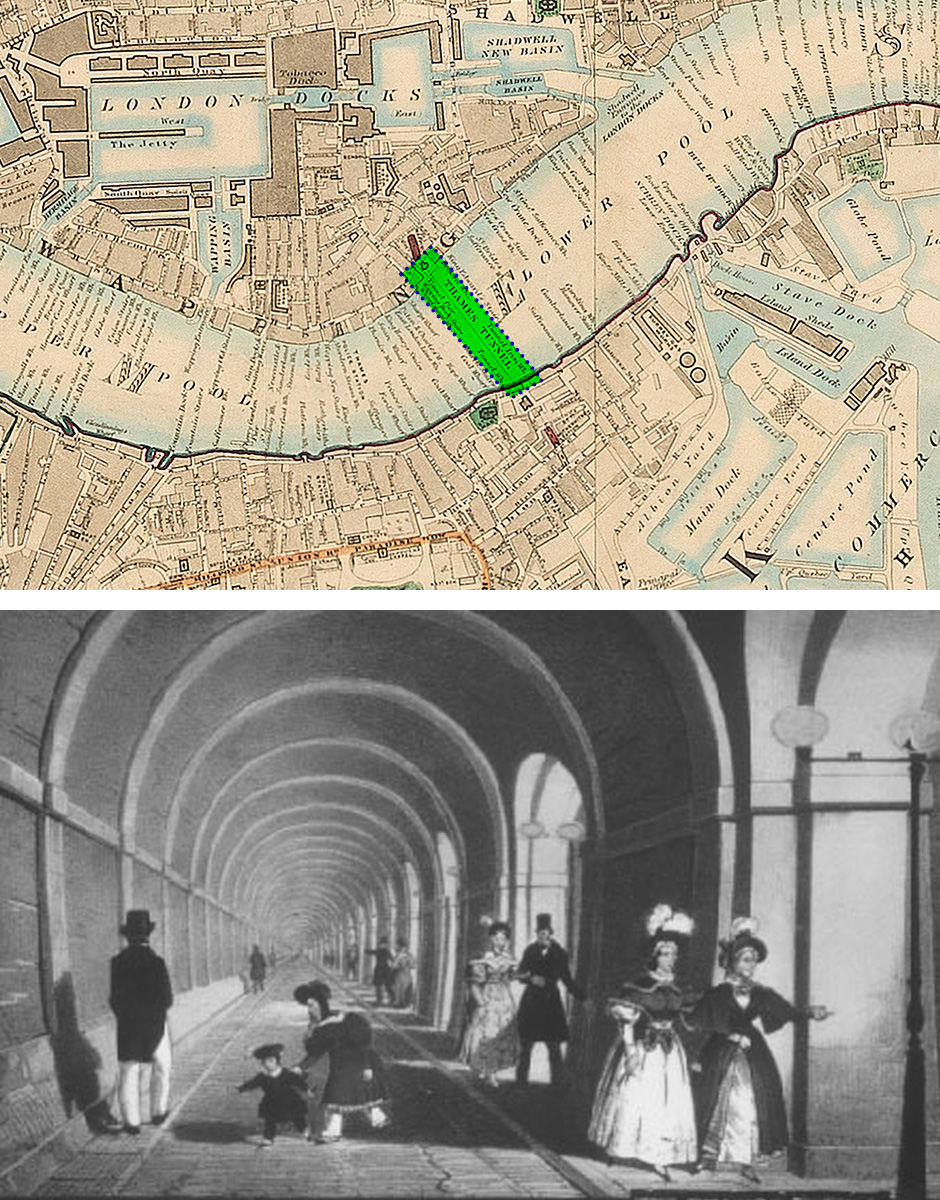

Thames Tunnel in the mid-19th century

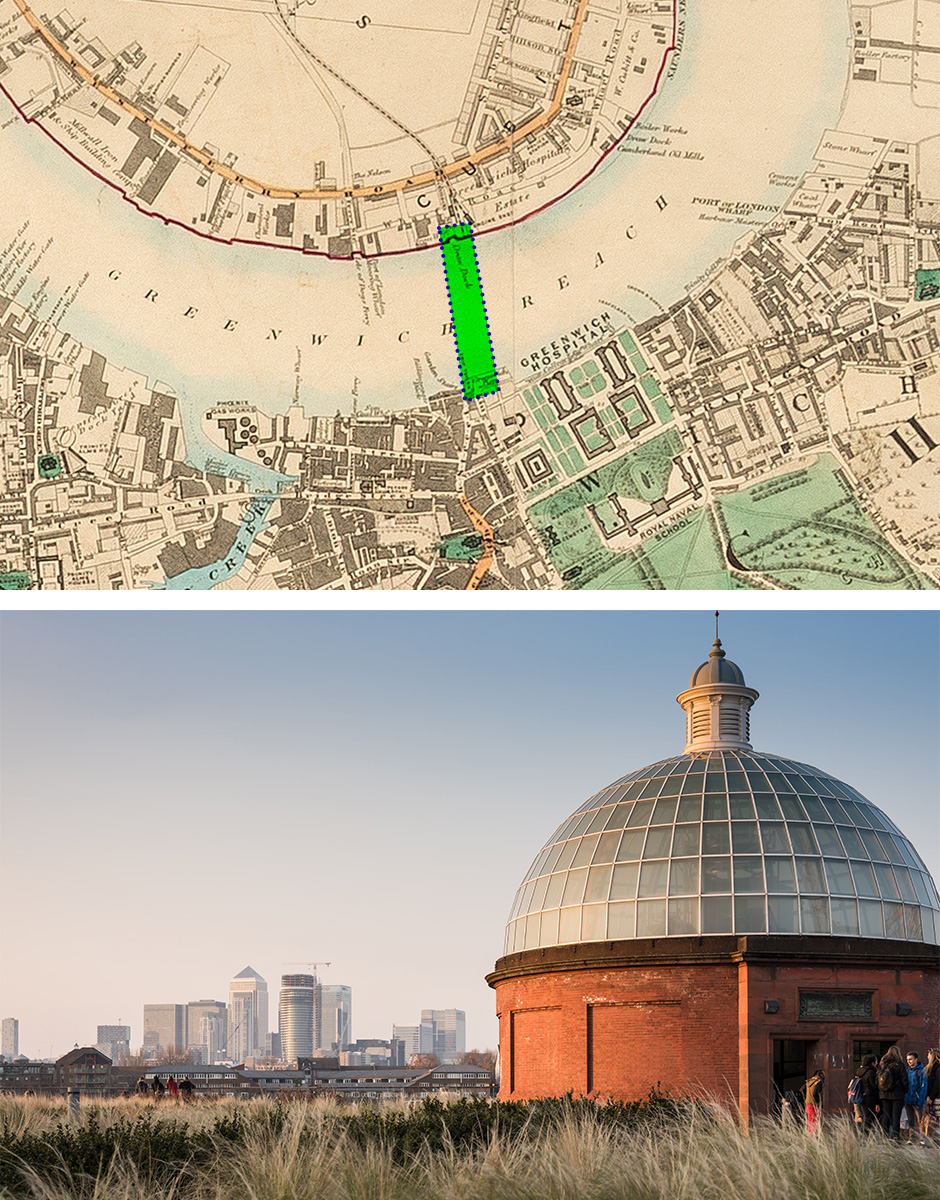

Entrance to Greenwich foot tunnel with Canary Wharf in the background

“In a time of innovation, the Victorians were keen on exploiting all the space in the city and leading the way was one family of exceptional engineers”

Foot tunnels

Why go over when you can go under? In a time of innovation, the Victorians were keen on exploiting all the space in the city and leading the way was one family of exceptional engineers.

Built by the Brunels (Marc and his son Isambard) and connecting Rotherhithe to Wapping, the Thames Tunnel opened in 1843. It was originally intended for carriages but fast became a tourist attraction. As the Industrial Revolution rumbled on the tunnel was repurposed and turned into railway tunnels, today forming part of the London Overground rail network.

Started in 1899 and completed in 1902, the Greenwich Foot Tunnel connects The Isle of Dogs with Greenwich and, unlike the Thames Tunnel, is still in use for pedestrians. Originally commissioned to make the commute for dockers and stevedores easier, today it’s mainly used by tourists visiting Greenwich’s maritime quarter.

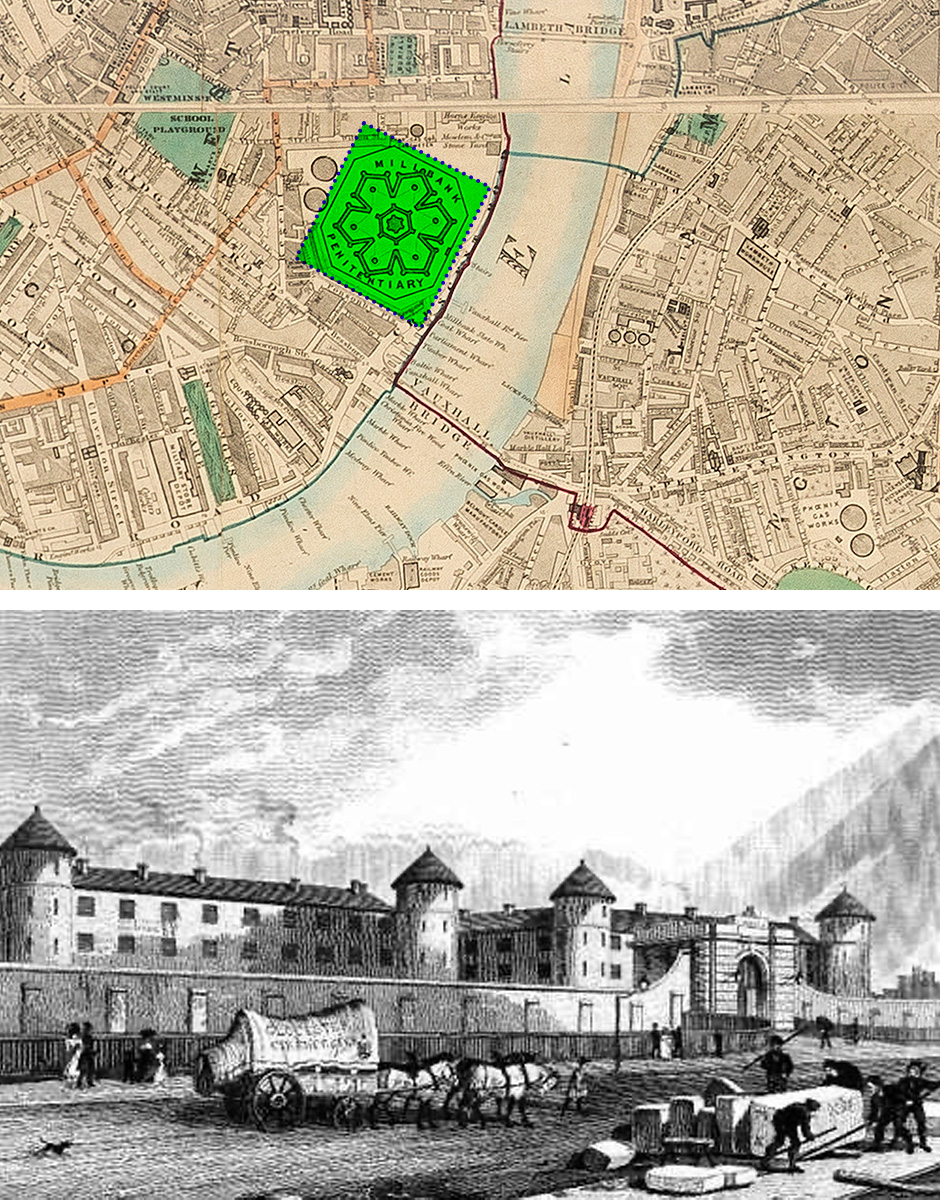

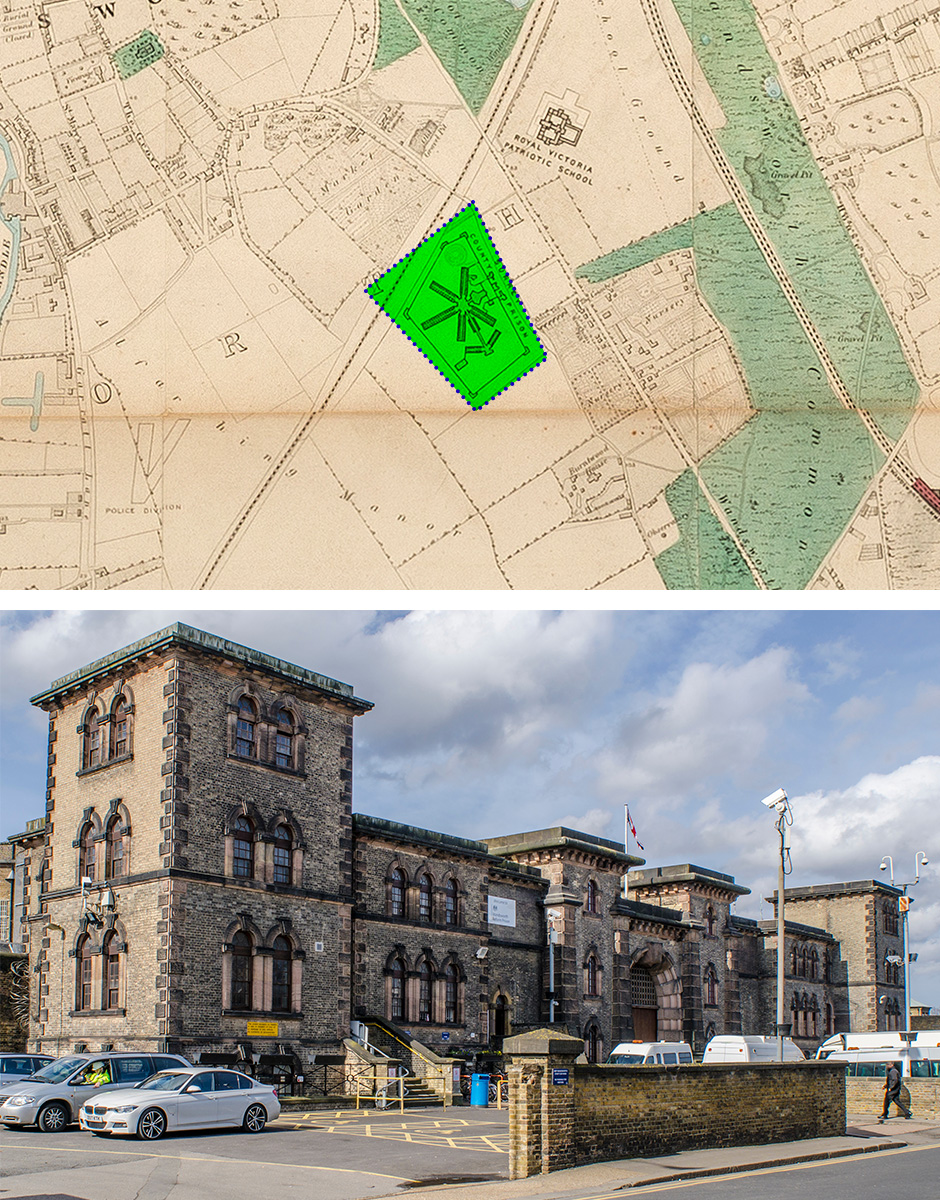

Millbank Prison in the 1820s

Wandsworth Prison

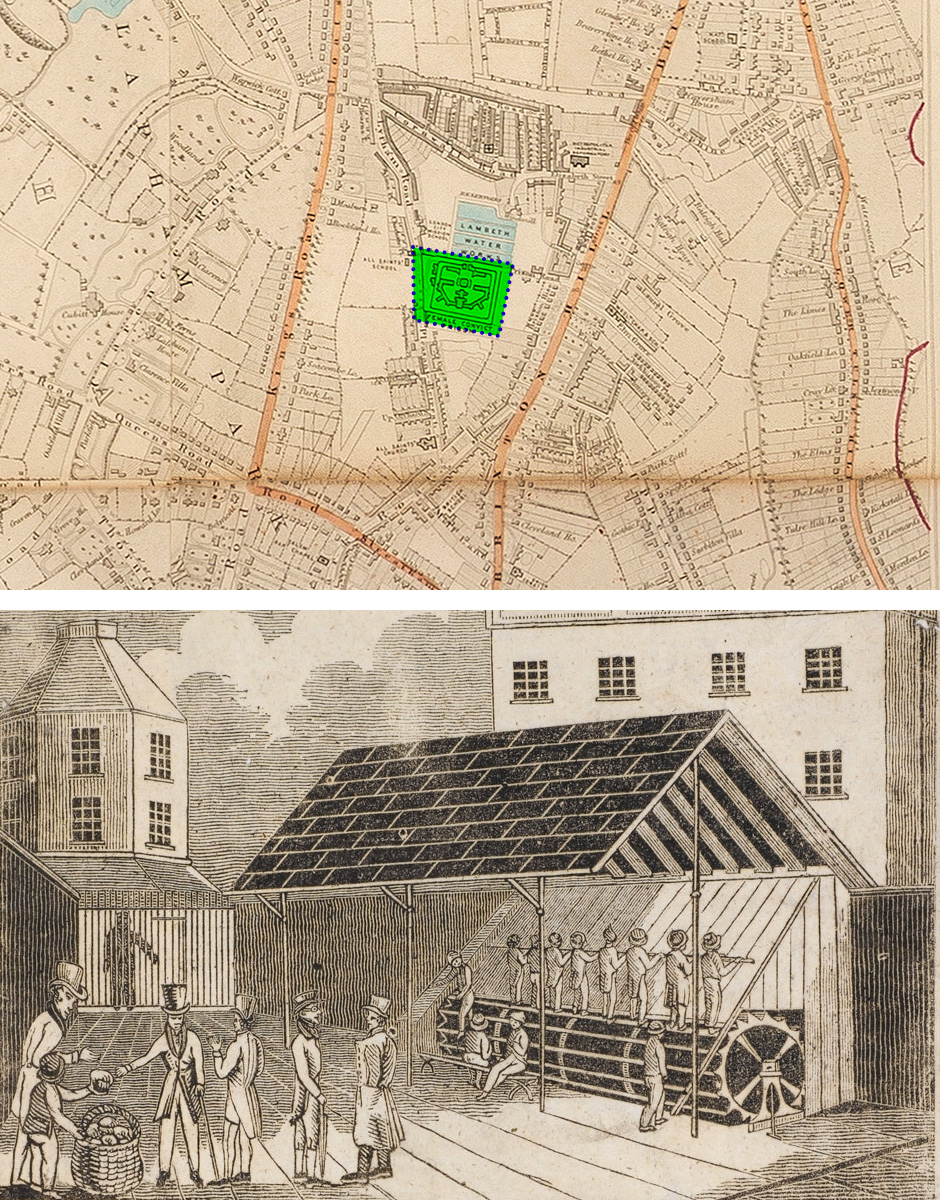

Treadmill at Brixton Prison circa 1817

Prisons

Prisons were big business in 1862, with dozens of ‘houses of correction’ peppered throughout the city and its suburbs.

Looking at the map in detail, there’s one structure in the heart of Westminster that stands out – Millbank Penitentiary. This huge structure just a few hundred metres from the Houses of Parliament was less a prison and more a holding facility for prisoners being transported to Australia. It had a short life - it was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890, with demolition taking place shortly thereafter.

In the capital’s southwest and recently in the news is Wandsworth Prison. Opened in 1851, the prison has a grisly reputation for hosting 135 executions between 1878, when the gallows were first installed, and 1961, when capital punishment in the UK was nearing its end. (The death penalty ended in 1965.)

Also on the map, and still in use, is the UK’s first female convict prison (now Brixton Prison). By 1862 it had a terrible reputation for overcrowding and hard labour – it was one of the first sites to use penal treadmills, acquiring its own in 1821. Fast forward to 1967, no longer a female prison, the jail acquired its most famous inmate, Mick Jagger. However, he served just one day of a three-month sentence for drugs possession.

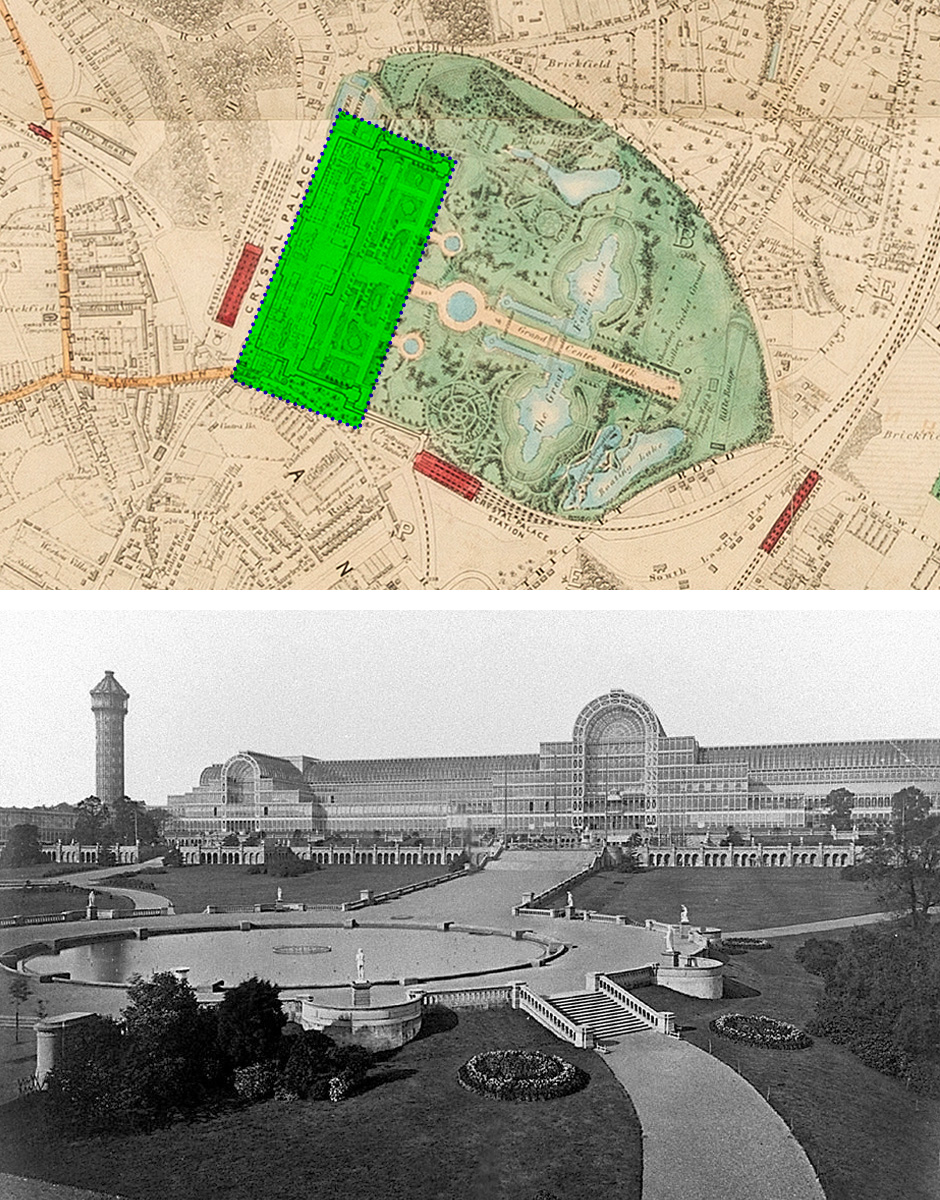

The Crystal Palace at Sydenham in 1854

“The Crystal Palace was a staggering feat of engineering”

A lost icon

The International Exposition – a showcase for advancements in mechanics and engineering – taking place in late 1862 would evoke for many Londoners the Great Exhibition of 1851. The pet project of Prince Albert, the Exhibition brought together 14,000 exhibitors over 990,000 square feet (92,000 m2), all housed in The Crystal Palace.

Designed by Joseph Paxton and completed in 1851, The Crystal Palace was a staggering feat of engineering with more than 5,000 people working on construction over the course of the build (with 2,000 on site at peak times). Its original home, just above Rotten Row in the south part of Hyde Park ensured easy access for all visitors, but it didn’t stay there for long.

In 1852, the Palace was relocated to Sydenham Hill and, in another example of Victorian industrialism, two railway stations were built and opened to ensure easy access to the permanent structure. After decades of decline, the Palace was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Westminster Palace Hotel 1860, from illustrated London News

“I am delighted that this map has been showcased. The RICS Library is a treasure trove of amazing items, some dating back to the 15th century” Fiona Fogden, Knowledge and Information Services Manager at RICS

RICS

Looking a little closer to home, the 1860s proved to be an important decade for RICS. Originally called the Institution of Surveyors, it was founded after a meeting of dozens of surveyors held at the impressive Westminster Palace Hotel.

The hotel, a stone’s throw from the current London office and opposite Westminster Abbey, was opened in 1860 and prided itself on deploying the latest tech for the comfort of its guests - it was the first hotel to use hydraulic lifts to shuttle guests to the higher floors with minimal effort.

Looking at the map, in 1862 the site of RICS London office (designed by Alfred Waterhouse and opened in 1896) is occupied by the National School, of which we’ve been unable to unearth much detail. Also detailed is the statue of George Canning, former prime minister which still stands today.

And the Institution has always been in good company; RICS’ neighbour on Great George Street, the Institute of Civil Engineers, has been its neighbour for a very long time. The map shows the Institute occupying offices on Great George Street in 1862, on the site where HM Treasury is today.

If this feature has got you wondering what else is in the RICS archives, take a look at the RICS Library catalogue here.