Queen of the Missions

Legend has it that the animals first noticed an earthquake was coming.

According to the Santa Barbara Morning Press: “Dogs ran helter-skelter with a bewildered look, some howling mournfully. Chickens began a barnyard chorus in all parts of town and flocked together in corners of pens. Cows and horses snorted and pranced while cats crouched in seeming fear from an unknown danger that confronted them. Birds flocked together on wires and chirped continuously for several minutes before the first shock was felt.”

Then, at 6:44am on Monday 29 June 1925, the ground began to shake. A magnitude 6.3 quake rumbled through Santa Barbara, a city 140km up the California coast from Los Angeles. When the ground finally settled – though aftershocks persisted up to a year later – the oceanfront enclave’s downtown was in tatters.

Up to 85% of the commercial building stock was damaged or destroyed. A dam failed and over 113m litres of water gushed through the town, flooding streets and buildings. Thirteen people died in the disaster.

As city leaders picked up the pieces, they made a pivotal decision that would influence Santa Barbara’s future: Not only would they rebuild with stricter codes to survive future earthquakes, they would also mandate a distinct aesthetic. Henceforth, the city founded by Iberian missionaries and soldiers would reflect its history through architecture, with buildings conforming to the Spanish Colonial Revival style.

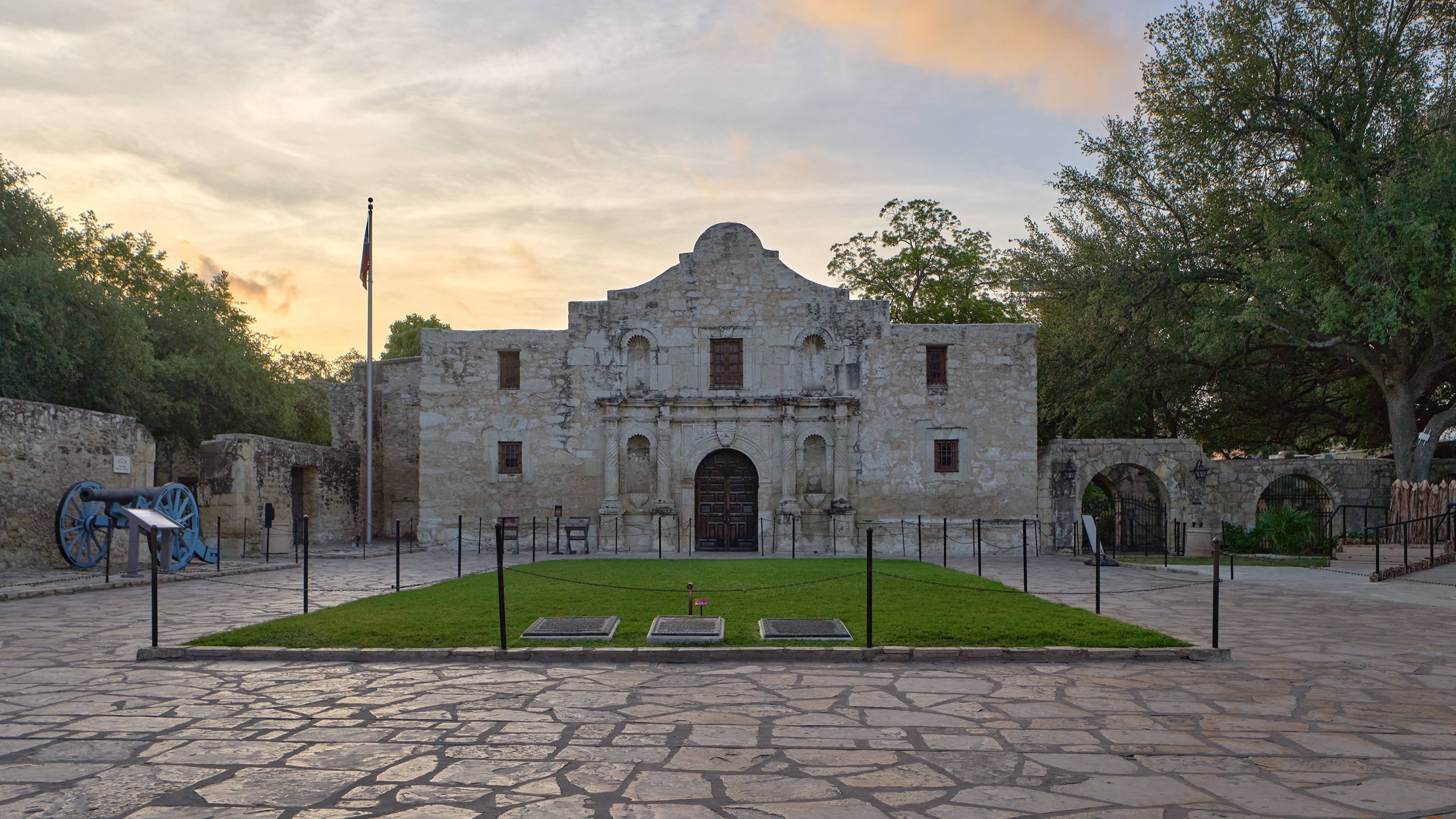

The landmarks that guided this choice were the original monuments left by the town’s first European settlers. El Presidio de Santa Bárbara, established in 1782, was the last of four military installations that the Spanish constructed in “Alta California,” as they referred to the modern-day US state (in contrast with Baja California, today part of Mexico). The Mission Santa Bárbara, founded in 1786, was the 10th such religious outpost and was known as the “Queen of the Missions.” In the wake of the earthquake, these historic structures were rebuilt or restored to period standards.

Queen of the Missions

El Presidio de Santa Barbara

Queen of the Missions

In the case of the Presidio, two buildings on the 5.5-acre campus survived: El Cuartel and the Cañedo Adobe. The former served as soldiers’ quarters and is the second-oldest building in the state of California. The latter is named for a soldier to whom the building was deeded over when the Presidio ceased to serve as a military installation.

But as the post-earthquake decades wore on, the city of Santa Barbara was rebuilt around these structures. While new commercial buildings conformed to the requirements of the Spanish Colonial architectural style, defined by markers such as white adobe or stucco walls, red-tile roofs, arched doorways and iron accents, there was no permanent protection in place for the Presidio. Indeed, a jumble of 19th and early 20th century buildings crowded the surrounding blocks, including part of the footprint of the original Presidio.

The potential risks to the city’s foundational site prompted civic activist Pearl Chase, a critical voice in the post-earthquake reconstruction vision, to found the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation in 1963. Under Chase’s leadership, the Trust embarked on a novel approach that it continues to this day: it acquires and rehabilitates historic sites, then in many cases sells them to California State Parks. In those instances, the Trust enters into agreements permitted under state law to manage the sites on behalf of the public agency. The Trust assumes the responsibility of maintenance and restoration, while also generating revenue from visitor fees and rental income to sustain its work.

Over its history, the Trust has sold 16 properties containing more than 38 buildings to California State Parks. Since the 1980s, the Trust has benefitted from the valuation expertise of Michael Neal Arnold MRICS, a certified appraiser at Hammock, Arnold, Smith & Company who has handled the intricacies of valuing Santa Barbara’s historic properties.

For example, an adobe building might have walls twice as thick as a traditional wood frame building, yet net rentable area is measured from outside the walls. So on the one hand, the building has a smaller commercial space that would reduce its value, but on the other hand, it has unique historic attributes that would increase its value.

“We are very conscious of being both landlords and general stewards of the Presidio’s surrounding neighbourhood” Michael Neal Arnold MRICS, Hammock, Arnold, Smith & Company

Courthouse and surrounding areas

Michael Neal Arnold MRICS. Photo courtesy of Hammock, Arnold, Smith & Co.

State Street, Downtown

“What we have here is unique in terms of the cost and expertise associated with fixing up old buildings” Michael Neal Arnold MRICS, Hammock, Arnold, Smith & Company

The Trust’s first surveyor as president

Arnold has acquired a knack for balancing competing concerns, plus navigating the lack of reliable comparable properties, all to the satisfaction of the prospective buyer in California State Parks.

“He was one of the most important people in all these transactions,” says Jarrell Jackman, the Trust’s executive director from 1987 to 2016. “He’s a really good presenter – calm, command of the facts.”

In 2012, Arnold joined the Trust’s board of directors and has served as president since 2022. “I'm the first surveyor to serve as Trust president,” Arnold says. “I bring an understanding of property economics that’s made me a more effective president.”

The fruits of his appraisal work have helped the once all-volunteer organisation mature into a professional real estate enterprise with nearly two dozen staff. That progression has given the Trust an outsized role in the look and feel of downtown Santa Barbara’s El Pueblo Viejo Landmark District.

“We are very conscious of being both landlords and general stewards of the Presidio’s surrounding neighbourhood,” says Arnold.

Arnold graduated from the University of California, Santa Barbara with a degree in geography. As he established his appraisal practice with the Trust as an early client, he reached a pivotal juncture in 1987. A donor had gifted the Trust two properties: Casa de la Guerra, an early 19th century adobe house built for the Presidio’s then commandante José de la Guerra, and the shopping centre El Paseo, which wraps around the U-shaped house. The Trust’s leadership determined it was unwieldy to manage a commercial shopping centre and split the two properties, retaining Casa de la Guerra (which the Trust owns to this day and operates as a museum) and putting El Paseo on the market.

The latter was built shortly after the earthquake as an early adopter of the new downtown’s Spanish Colonial Revival style. The public – and several of the Trust’s membership – had a significant emotional attachment to this prime example of post-earthquake architecture and objected to the Trust’s plans to sell. Arnold ended up walking the public through his valuation live on stage at a downtown theatre in front of an audience of hundreds and television news cameras.

“It was an explosive issue,” Arnold recalls. “Most property valuations are prepared in written reports that are seen by relatively few people. So this was a memorable occasion.”

The sale proceeded to a private developer, which netted the Trust further properties it sold to California State Parks. Additional proceeds were invested to become the basis for a large part of the Trust’s endowment. Above all, Arnold’s fair-minded valuations were important for maintaining the trusting relationship between the Trust and California State Parks.

“Not a single one of his appraisals was ever disputed,” says Jackman.

Overlooking downtown Santa Barbara

Jimmy's Oriental Gardens. Image courtesy of Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation

Our Lady of Sorrows Church

Creative Trust management

By selling to the state, the Trust can offload properties from its rolls and free up capital for future acquisitions. But by maintaining management responsibilities, the Trust ensures that historic buildings requiring specialised care and attention do not fall victim to public sector budget cuts. The Trust can pursue grants and dedicated fundraising with a singular focus on its properties, rather than having to triage between a statewide portfolio.

“They can be creative in ways that government can’t,” says Dena Bellman, Channel Coast District Superintendent for California State Parks.

One of their most creative revenue streams comes from leasing properties to small businesses. Downtown Santa Barbara is coveted commercial real estate with high foot traffic in a city of affluent residents and steady tourism.

An 1896 house is home to a sandwich shop. A 1920s arts complex is home to a theatre and two restaurants. In 2007, the Trust acquired Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens, a Chinese restaurant that closed with the retirement of its second-generation owner. The Spanish Revival building only dates to 1947, but the building represents the city’s social history – it speaks to Santa Barbara’s waves of immigration. Since the building operated as a restaurant historically, today it’s still home to food and beverage tenants, whose proceeds help with historic upkeep.

“There are restrictions on the income that comes off of these properties, mainly that we are totally responsible for the maintenance of the buildings,” says Arnold.

Over time, the Trust has acquired a roster of skilled craftspeople capable of working on buildings from the 18th to the 20th centuries – from adobe makers to brick masons to roofers who specialise in installing fired clay tiles. At times, the Trust has even mixed its own paints and made its own stain from iron oxide, linseed oil and turpentine. “What we have here is unique in terms of the cost and expertise associated with fixing up old buildings,” says Arnold. “And we’re still renovating.”

Indeed, the process for restoring buildings is painstaking. The Trust employs archaeologists and runs its own archaeology laboratory, which has conducted extensive surveys underneath the downtown footprint since the 1960s. Not only has the lab provided educational opportunities for budding archaeologists at California universities, it has also excavated tens of thousands of artifacts. The Trust maintains a dedicated Presidio Research Center that houses thousands of books and journals dating to the 18th century, as well as 1,000 objects.

Today the Trust manages 40 buildings, with 32 of those in the foundational El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park. As of late, the Trust’s acquisitions have slowed down as the downtown approaches saturation – essentially, there are very few historic buildings left where the Trust does not yet have some kind of architectural easement or management responsibility – but the Trust has spread its wings beyond the urban core. In 2008, the Trust completed the successful sale of the Santa Inés Mission Mills complex to State Parks, having rehabilitated a historic grist mill and masonry reservoirs from the early 19th century while retaining management responsibilities for six buildings.

With fewer new renovations in demand – though restoration of the 1871 Cota-Knox House is ongoing – Arnold says the Trust’s mission has shifted. “For the first 50 years of the Trust, the main orientation was project oriented – restoration and recreation – but it's been expanding now more into program-oriented activity,” he says. That new focus includes programming to connect the area’s ethnically diverse residents, like hosting an Asian American Film Series and a monthly makers market for women of colour. There is also now a representative of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, the area’s original inhabitants, on the Trust’s board.

While a thriving, cosmopolitan city blessed by the Mediterranean climate of the California coast may have seemed an impossible dream in the wreckage of June 1925, 100 years later Santa Barbara respects its past while planning for its future.