Tamil Nadu, a state in southern India along the Bay of Bengal, sits squarely in the Indian Ocean cyclone belt. As a child in the 1990s, Rohini Sampoornam Swaminathan vividly remembers the dire straits facing her family when one of these tropical storms made landfall in Tamil Nadu.

With just a tarpaulin hut to call home in the forest hamlet of Tiruvannamalai, their meagre shelter was no match for the lashing winds and pelting rain that accompany cyclones. During one particularly intense cyclone (also known as hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean and typhoons in the Pacific) Swaminathan recalls: “My parents and sister put me under a truck. I screamed, passed out, and woke up in the morning.”

In December 2016, Swaminathan was visiting her family when Cyclone Vardah hit. The eye passed directly over her hometown. And yet, she was struck by how fewer homes and businesses were damaged compared to the experience of her childhood. “The streets were still flooded, but there was a big difference in how much better prepared we were,” she says.

By the 2010s, most buildings in the town were made of concrete.

A career in geomatics

For 32-year-old Swaminathan, her personal life was on-the-ground evidence of the phenomena she studies as a geomatics expert currently serving as the head of the Geospatial Support Unit for the World Food Programme (WFP).

Swaminathan is far from an armchair analyst content to study the world from behind a screen. She regularly rolls up her sleeves for volunteer assignments to work with Syrian refugees in Greece and Turkey or train with the Red Cross in Kenya. In this case, she was on leave during Cyclone Vardah from her job at the United Nations so she volunteered with local first responders. In the process: “I realised how useless the maps from my agency were,” she says. Grassroots organisations mapped out flooding by WhatsApp and Google Earth more accurately than satellite data. “Participatory mapping made a huge difference for first responders.”

“When you’re seeing from the outside you don’t get the full picture,” she says. “Those personal experiences influenced how I think about my work.”

Lessons for surveyors

Her work is predominantly geared for development professionals, humanitarian relief workers and government agencies engaged in disaster preparedness and recovery. But there are broader lessons for surveyors, especially those working in developing countries, from the application of geospatial technology to disaster risk.

“You don’t want to build where there is a high chance of flooding,” she says. “In planning that level of detail, geospatial technology becomes indispensable.”

Fortunately for surveyors, the United Nations (UN) makes many of its geomatics tools available to the public. In her current role at WFP, Swaminathan oversees the Automated Disaster Analysis and Mapping to which anyone can subscribe and receive alerts on tropical storms, earthquakes and floods – there’s even a Twitter feed. The agency is in the process of expanding the service to offer early warning, response information and impact estimation, as well as cover a broader range of hazards.

As secondary sources, Swaminathan recommends UNOSAT and Copernicus EMS for learning more about how satellite data is used for disaster risk and response mapping. She also suggests UN-SPIDER for a how-to on using space-based technology.

Swaminathan credits her choice of career to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, whose after-effects she observed first-hand when accompanying her civil servant father to the disaster scene. But she credits NASA, the US space agency, for sharpening her skills and enabling her to become a groundbreaking geospatial analyst. During her first two years out of graduate school, she worked at DEVELOP, NASA’s applied earth sciences programme focusing on applications of satellite remote sensing for environmental management, especially in developing countries.

“There has been a massive investment in disaster risk reduction over the last 20 years, using satellite-based monitoring” Rohini Sampoornam Swaminathan, UN World Food Programme

Applying the technology

As she studied flooding and drought patterns in Mexico, or water management systems in Peru, from NASA’s headquarters, she was at the enviable intersection where cutting-edge technology meets on-the-ground application. “When you use a satellite, you can talk to the scientist or engineer that designed the satellite and connect the technology to real-world problems,” she says.

After NASA, Swaminathan worked with various branches of the United Nations: United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Health Organisation (WHO), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and now WFP. The transition gave her a front-row seat to natural disasters and humanitarian relief missions. Suddenly the stakes were much higher. “I went from a research world to an operational world,” she says. “In research, I can write a report that a methodology didn’t work. At the UN, whatever you do has direct implications on the ground.”

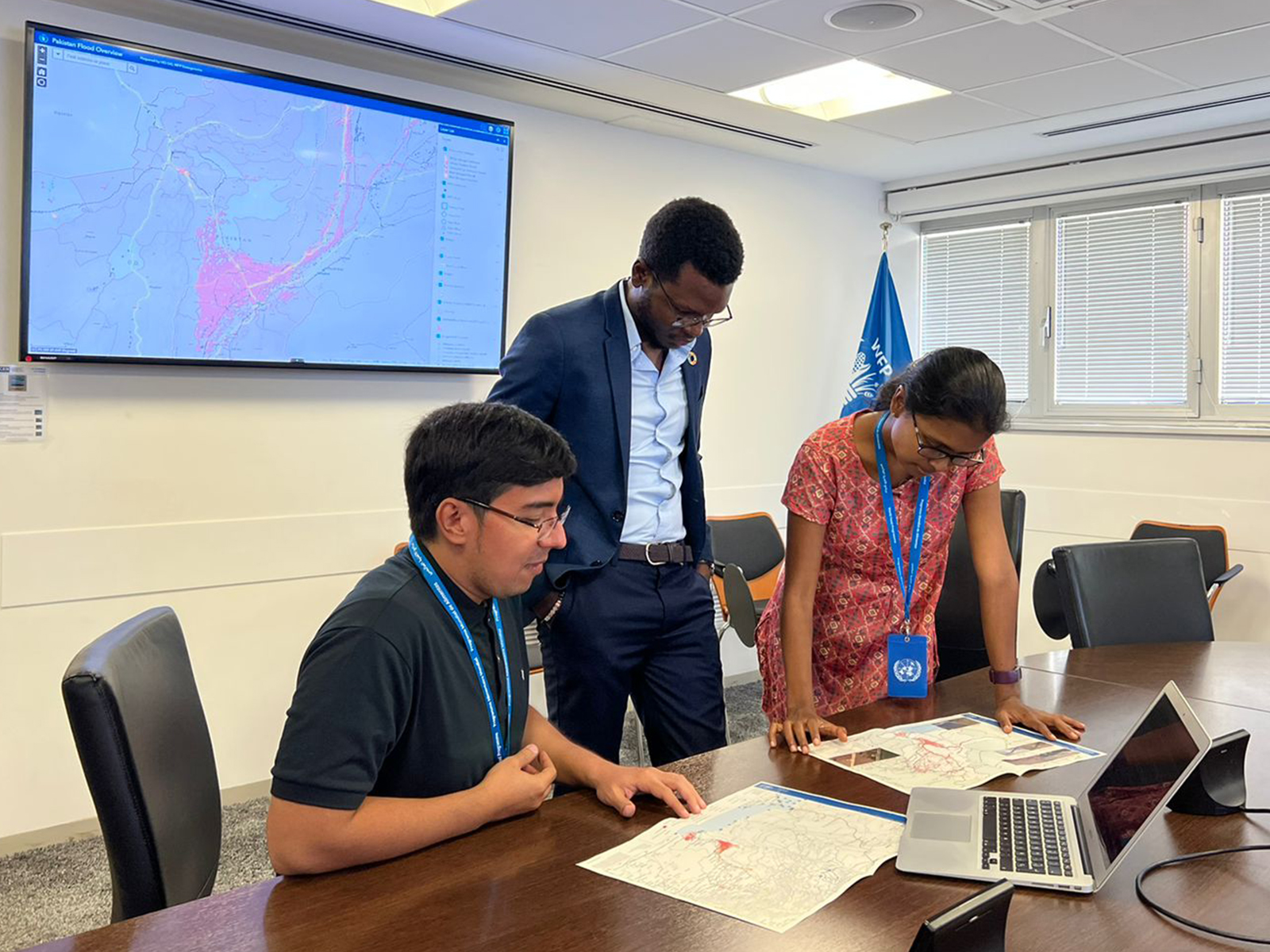

For example, imagine a hypothetical earthquake in Afghanistan – like the 5.9-magnitude quake that hit on 22 June 2022. The UN automatically puts together a geospatial analysis drawn from satellite data and modelling tools to conduct a damage assessment of buildings, roads and bridges.

The analysis is then sent to country offices that are likely to be responding in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, to guide operational decisions. “We can’t send a convoy of 100 vehicles that will get stuck in the middle of nowhere,” she says.

In a world that seems increasingly beset by natural hazards, with the Northern Hemisphere summer of 2022 featuring countless heatwaves in North America, Europe and South Asia as well as deadly flooding in Pakistan and the US, geomatics is now a frontline tool.

“Using geomatics used to be a luxury in this world, but not anymore. Almost all major UN agencies have adopted spatial analysis to better understand the risks and improve emergency preparedness,” Swaminathan says. “I believe evidence-based information is a key to decision making, and remote sensing plays a central role in generating that. To be able to visualise where risks are (not just the hazard, but also mapping the vulnerability and exposure) can help us best prioritise our interventions.”

“Countries with stronger building codes and stricter requirements suffer less damage from disasters of almost equal magnitude” Rohini Sampoornam Swaminathan, UN World Food Programme

Planning for disaster

For property developers, these kinds of models and assessments could be useful for monitoring their portfolio should a disaster hit. But the real value comes from the long-term preventive planning that Swaminathan’s field offers. As she noted in a 2016 TED Talk, There is nothing natural about disaster, 2010 saw two serious earthquakes in the Americas. A 7.0-magnitude quake besieged Haiti and left 300,000 dead according to official counts. Chile withstood a magnitude 8.8 quake that killed around 500 people. The latter earthquake was 63 times bigger – the Richter scale that measures earthquakes is logarithmic – and yet caused a fraction of the fatalities.

Building codes were a crucial factor in the lower death toll in Chile. Public policy enforces tight building codes and retrofits in this seismically active country, which experienced the 9.5-magnitude Valdivia earthquake in 1960, widely considered the strongest earthquake ever recorded. In the wake of today’s disasters, like the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that galvanised Swaminathan, geomatics play an increasing role in determining exactly what and where the risk factors are in the face of natural disaster.

While Swaminathan uses geospatial information systems to help the UN find suitable sites for schools, hospitals and emergency shelters, she argues for the necessity of the built environment sector also embracing these disaster forecasting tools to make buildings more resilient.

“There has been a massive investment in disaster risk reduction over the last 20 years using satellite-based monitoring,” she says. “We have been able to see this over and over again – countries with stronger building codes and stricter requirements suffer less damage from disasters of almost equal magnitude.

“Disaster risk reduction measures at the community level are the best solution we have to reduce the impact of any major disasters.”