Few retail developments can claim to date from the 12th century. But the Bullring shopping centre in Birmingham can trace its history back to 1166, to a myriad of traders and market stalls, complete with iron hoops where bulls were tied before slaughtering, giving the site its name.

The 147,000m2 behemoth shopping centre that dominates the city centre is the 21st century replacement for the 1960s concrete mass, Bull Ring. It was considered revolutionary in its day, but decades of disrepair and neglect led to its demolition in 2000.

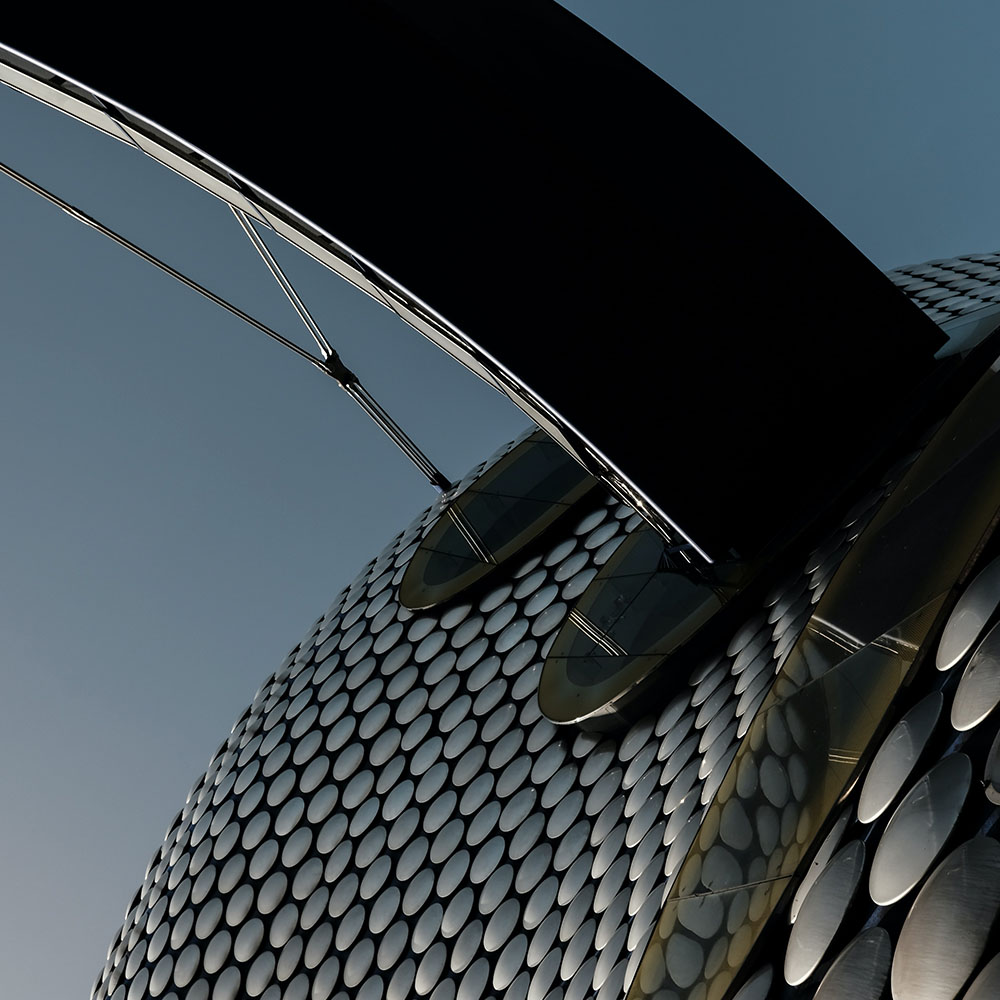

The name has subtly evolved from from Bull Ring to Bullring, and the modern-day retail emporium, surrounding St Martin’s Church, has become Birmingham’s most recognisable landmark. The space-age design and Selfridges flagship store have breathed life back into the city centre for its million-plus residents and become a postcard-worthy picture of the city.

However, the redevelopment was far from straightforward. In 1999, three property developers Hammerson, Henderson Global Investors and Land Securities formed the Birmingham Alliance. They worked with architects Benoy on a design that had to break through the ring road surrounding the centre: a concrete collar strangling the retail core.

“Birmingham was the home for the automotive industry and town planners prioritised motor transport,” says Catherine Hood, real estate partner at local law firm Shoosmiths.

A faded giant

Developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the original Bull Ring containing supermarkets, shops and market stalls was heralded as a truly modern shopping centre and was one of the world’s largest outside the US.

It was revolutionary and vibrant, says Hood. “The food markets were a real hub for the community. There were very few places like it … and it helped put Birmingham on the map.” But the first centre dated badly, becoming tired and faded, and by the 1980s it had only one department store.

James Utting, the design director of Benoy, who led the redesign team at the time, described the old centre as a “monolith” in a “no-go” area. The aim of the new Birmingham Alliance development, he said, was to break down the old building into a series of city blocks, create new spaces, while using “daring engineering” to connect the Bullring “back to its rightful place at the retail heart of the city.”

Given the complexities of the ring road, freeing the city centre from its concrete perimeter was the project’s biggest design challenge. The solution was to build a bridge across the railway and road tunnels below, using four bow-string trusses that suspended the new buildings.

“They created an icon that Birmingham could then rally around and promote itself on” Robert Bentley, Benoy

“The new Bullring was a catalyst for the statement architecture we now see in the city” Catherine Hood, Shoosmiths

Reconnecting the city

A key consideration was the reinstatement of the original street pattern and reconnection of the Smithfield market area, and the areas beyond, back to the city centre, says Robert Bentley, a director at Benoy.

“There are three levels of retail that gives the building enough height to get over the ring road – that’s why when you’re in the original city centre you walk up a slight hill: that grading is taking you over the road and you wouldn’t even know it was there. Thereby solving the vehicular barrier.”

Bentley says opening the street pattern, allowing the main shopping streets of New Street and High Street to flow into the Bullring, and restoring the view to St Martin’s Church, “the pedestrianisation of the route through and past the ring road … was absolutely bang on the money.”

Architect firm Future Systems, known for its ‘biotecture’ work using amorphous, organic shapes, was chosen to design the anchoring tenant site: the £60m Selfridges flagship store.

Vittorio Radice, the chief executive of Selfridges department stores, was a noted enthusiast of radical architecture and the new building in Birmingham had to make an impact.

“The resulting volume is brimming over with mass and form and clad in a futuristic mesh made up of 15,000 aluminium discs, reflecting changes with sunlight. It forms part of a vast project of urban refurbishment whose key purposes were to increase the amount of retail floor space and create pedestrian areas,” stated Arquitecturaviva.com.

For Bentley, Future Systems successfully announced Selfridges to the city: “They created an icon that Birmingham could then rally around and promote itself on. It provided an internationally recognised building on a ring road with gateway positioning. What a great thing to deliver.”

Paving the way for bold design

Hood says there was a fear the new Bullring could have been a white elephant type of development because of its bold statement design. However, she says: “It paved the way for other statement buildings in the city. Look at The Cube [hotel, residential and offices], Mailbox [retail and leisure], Grand Central [train station], and even the new library. Those buildings fit better in the urban landscape and people’s mindset because of the Bullring. The new Bullring was a catalyst for the statement architecture we now see in the city.”

Like retail destinations worldwide, the Bullring suffered during the COVID-19 pandemic, with its lockdowns and redundancies. It also had to contend with the shifting and evolving retail market. But says Bentley: “It’s a building that continues to evolve … and has that flexibility in its building structure and floorplate so it can continue to meet … the city’s dynamic [changes].”

The area around the Bullring is also evolving as it undergoes a major transformation driven by the mixed-use masterplans for Smithfield and Martineau Galleries. “Regeneration has changed since the current Bullring was built, and these [projects] will bring an increased focus on placemaking, with homes, hotels, and public realm,” says Hood.

While they were contrasting schemes, Hood says both the original Bull Ring and modern Bullring have changed the perception of the city for the better.

She says: “The new Bullring hasn’t dated or experienced the same fate as the first scheme, which did lose its appeal. It will need to continue adapting, but with gentle evolution I believe it can stand the test of time, remaining a bold symbol of Birmingham’s success.”