Welcome Centre at Community First! Village, Texas. Photo credit: ICON/ Regan Morton

In literature, ‘deus ex machina’ (god from the machine) refers to a tidy plot twist—sometimes actual divine intervention—that resolves a narrative problem. When it comes to the global quest for high-quality, well-designed housing that can be produced cheaply and quickly, proponents of a new building method promise ‘domus ex machina’ (home from the machine).

That, at least, was the Latin terminology that construction technology company ICON deployed in April at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Conference to unveil its latest iteration of 3D printed housing.

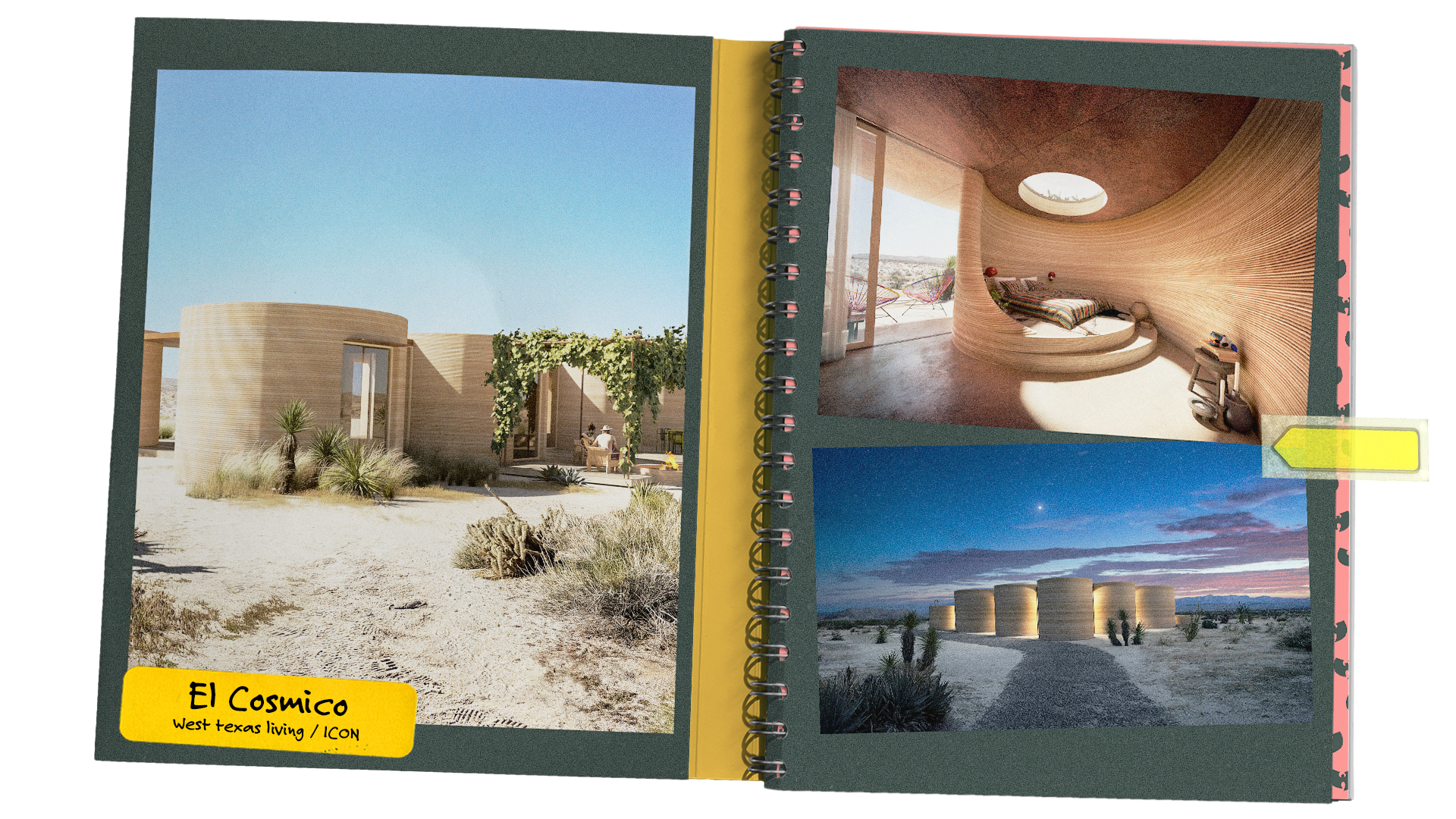

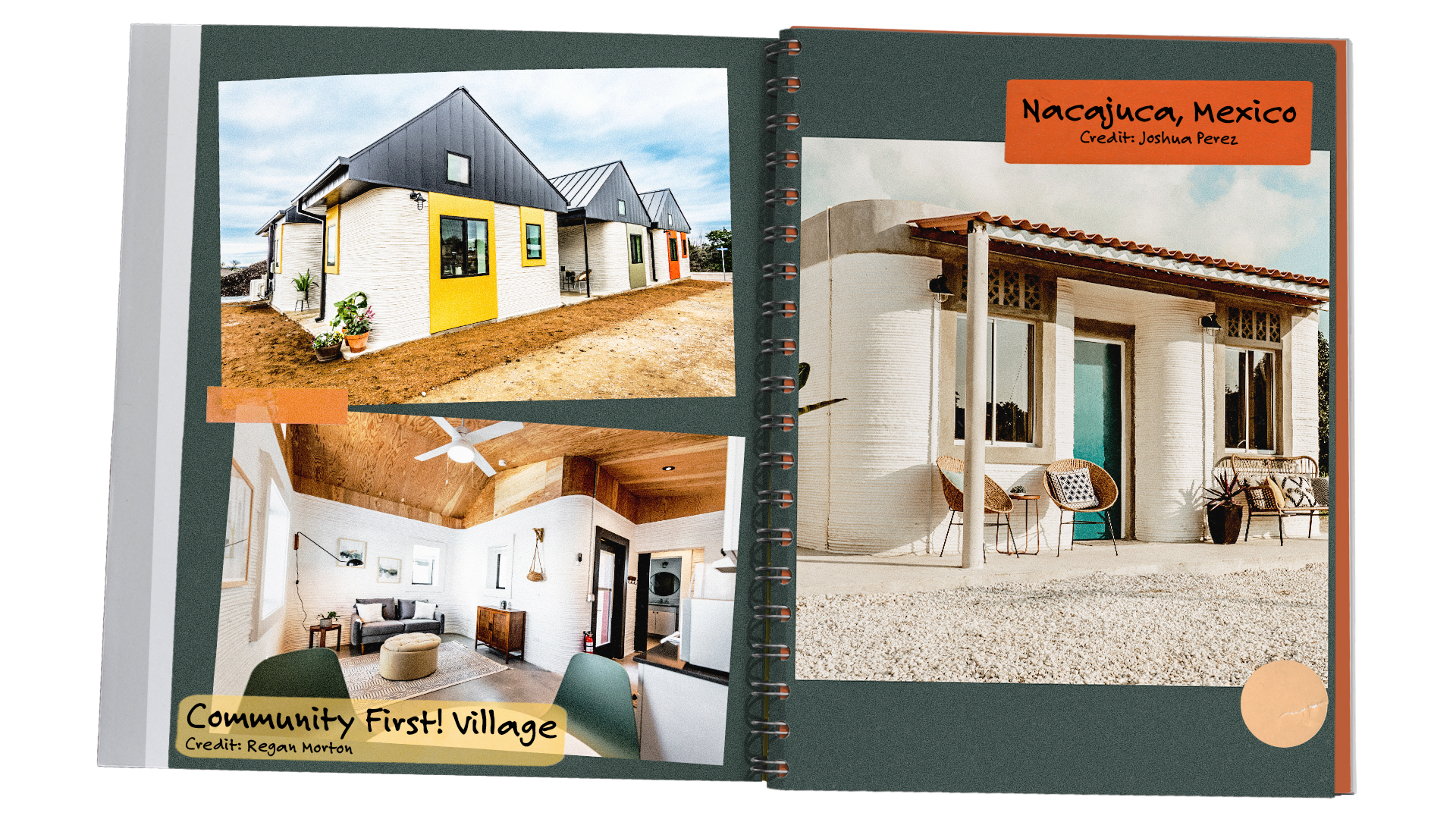

In 2018, the Austin, Texas-based firm turned heads in their hometown before a SXSW audience when they exhibited a 3D printed house that met US building codes: a 60 m2 single-storey concrete abode printed in two days for only $10,000 (£7,965). ICON has built 130 homes across the US and Mexico, which they claim is the most by any company working in the field of 3D printed construction.

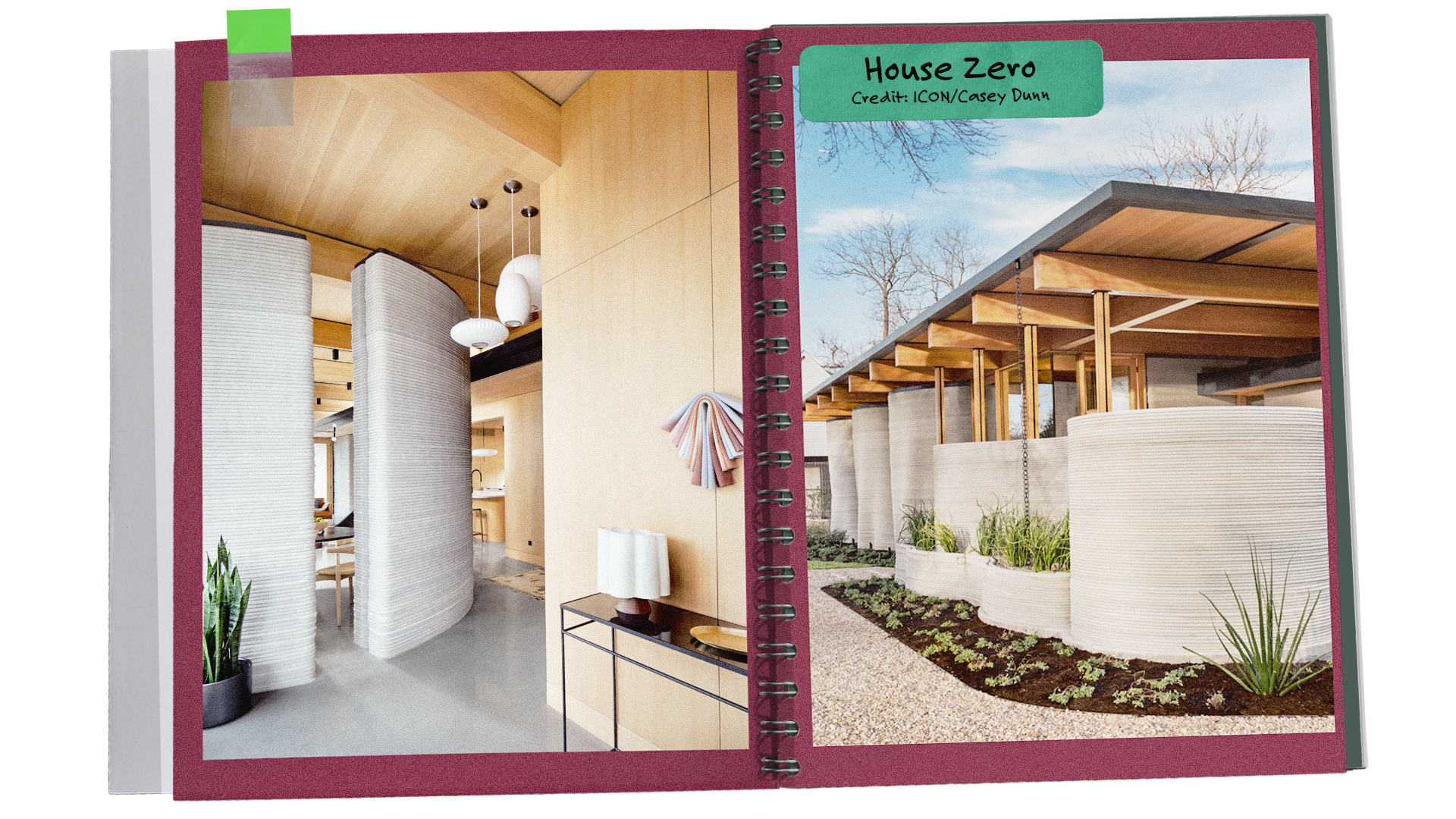

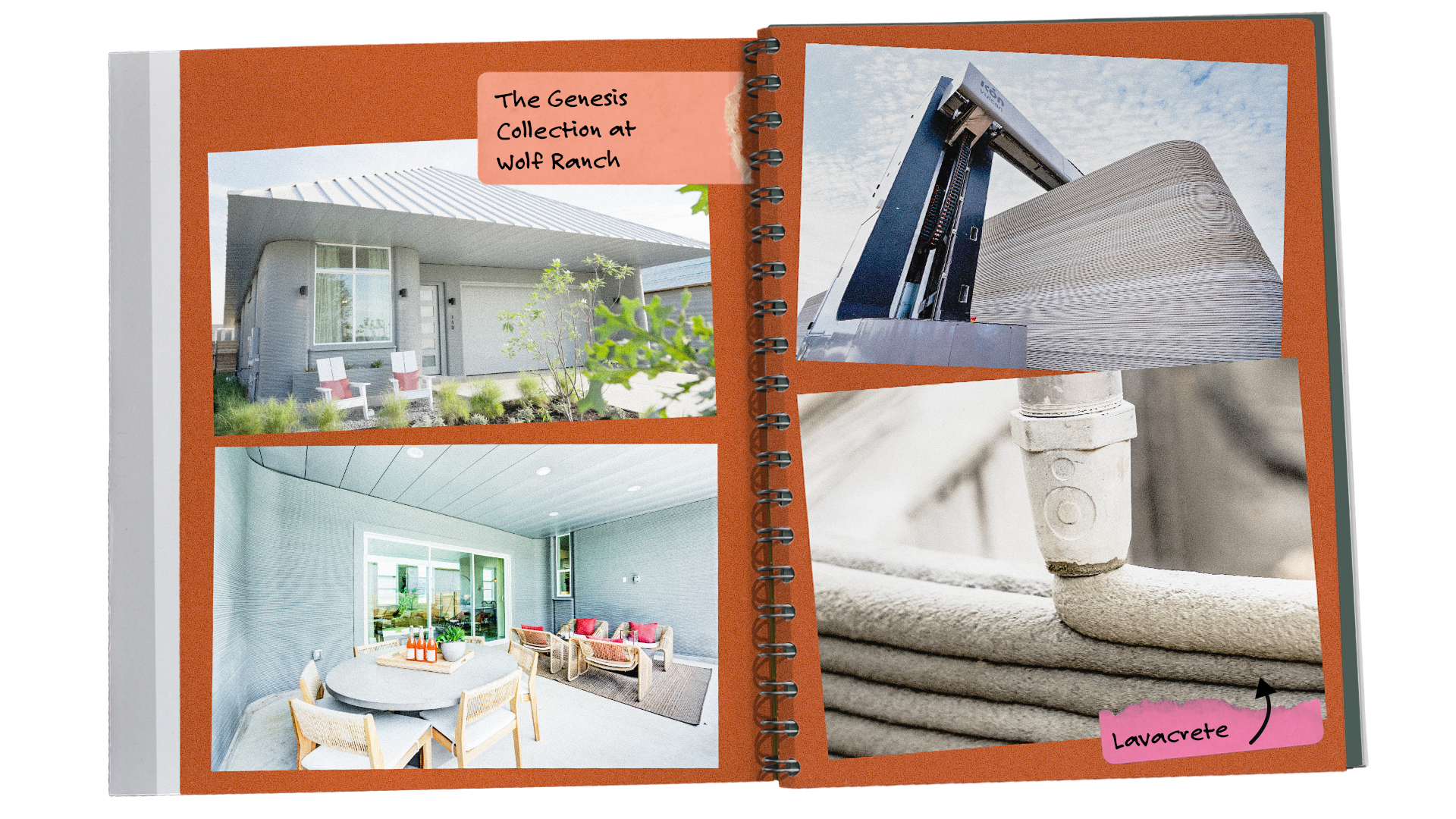

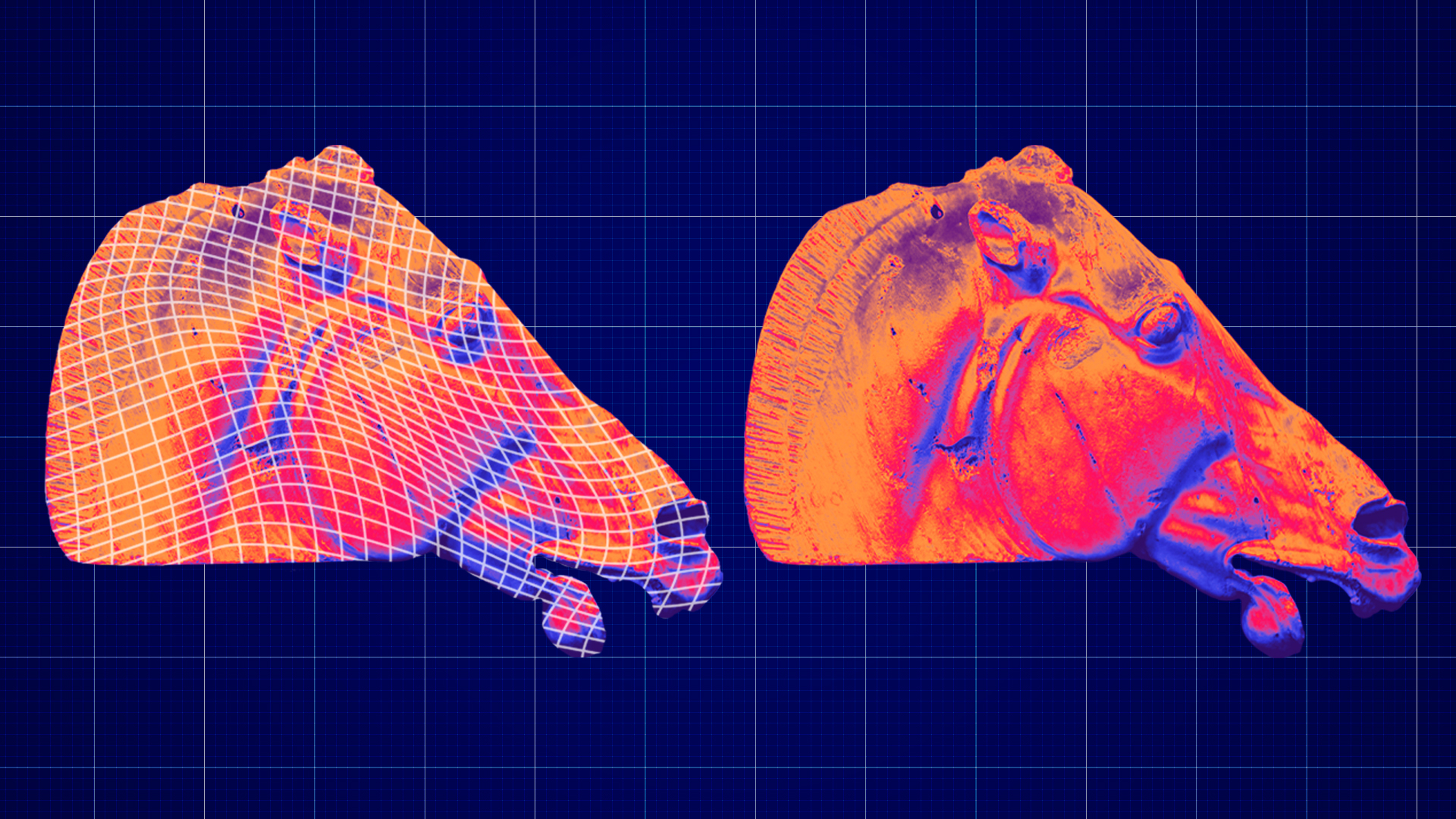

3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, is a process to turn digital models into three-dimensional objects. The printers themselves typically spit out thin layers of plastic to produce the physical form. When it comes to 3D printed housing, in turn, the material of choice is concrete. ICON’s first iteration of a printer big enough to build a house is shaped like a 46-foot-wide gantry, while its newest model has a swiveling robotic arm that allows for more precision application. A printer typically produces 10-15 mm of concrete per application, building layer upon layer, often giving the walls a ribbed texture in the finished product.

At this year’s SXSW event, ICON announced bold developments that could see this new construction technique scale quickly: lower-carbon concrete that can feed into a more advanced printer capable of tackling multi-storey construction, as well as a suite of 60 residential designs and architectural software powered by artificial intelligence to more quickly adjust homes to customer preferences.

“In the future, I believe nearly all construction will be done by robots, and nearly all construction-related information will be processed and managed by AI systems,” said ICON founder and CEO Jason Ballard in a press release after the launch of Domus Ex Machina.

“It is clear to me that this is the way to cut the cost and time of construction in half while making homes that are twice as good and more faithfully express the values and hopes of the people who live in them.”

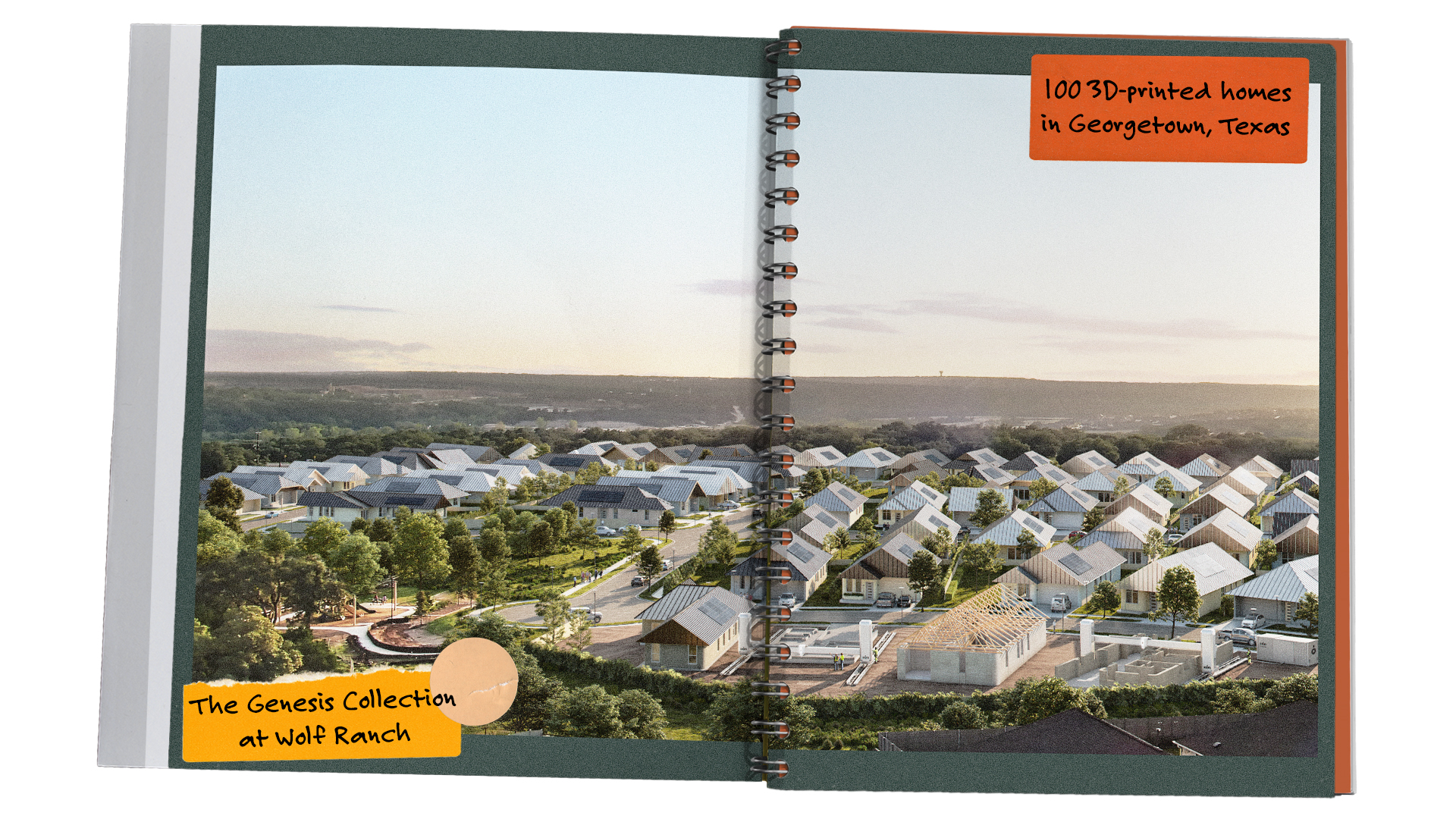

ICON is the nascent industry’s leading player, having formed partnerships with famed Danish architect Bjarke Ingels and US homebuilding giant Lennar to deliver on an entire subdivision, while most other start-ups have prototypes at best.

Affordable housing

The charity sector also sees potential in the technique. Citizen Robotics printed its first house in Detroit last year as part of a gambit to populate some of the 72,000 vacant lots in the post-industrial city with affordable housing. Habitat for Humanity employed 3D printing with the help of private firm Alquist to create new homes in Virginia.

While much of the trend is concentrated in North America, there are 3D printed structures on six continents, according to a 2023 survey by Danish additive printing firm COBOD International A/S. Those figures, while already outdated in the fast-moving industry, were nevertheless quite modest: just 129 buildings. COBOD, which built Europe’s first 3D printed building in 2017, has sold more than 50 printers capable of making such buildings. Most recently, a COBOD printer was the muscle behind the largest 3D printed structure on the continent, a 600 m2 data centre in Heidelberg, Germany.

Proposed alternatives to traditional methods like mason-built brick or site-built wooden frame houses are nothing new, of course. Prefabricated, modular and panelised construction – all increasingly popular responses to the 21st century’s housing supply crunch – trace their roots as far back as the 17th century, when English settlers brought panelised wooden houses to colonial Massachusetts. And yet, 97% of new housing in the US is still site-built, according to the Urban Institute.

But 3D construction advocates argue this time is different, given both skilled and unskilled worker shortages in the building trades, rising labour costs and supply chain constraints.

“You’re going to have leapfrogs because incremental innovation is not an option for the construction industry anymore,” says KP Reddy, a civil engineer by training who founded and manages Shadow Ventures, a seed-stage venture firm focused on the built environment, which has invested in ICON. “This is the first time where builders don’t have a choice.”

While ICON and its investors are true believers, independent experts like Dawud Muneer MRICS, senior specialist for construction and infrastructure management at RICS, concur that the technique has valid potential. “3D printing, as a modern method of construction (MMC) could have a transformative impact on how we build globally, resulting in building faster and more efficiently, while meeting ESG targets,” he says.

Customisable construction

3D printing also has the added benefit of customisation. “If we look back over the last five to 10 years, modular construction has risen in popularity. But perhaps the design aspect has its restrictions, which is prevalent in the use of steel, timber and composite sandwich panels built in high volume,” Muneer says. “Whereas 3D printing enables further flexibility in design and geometric freedom, given its use of concrete as the predominant material.”

Consequently, he believes the industry on a whole, should start to draw attention towards how this method could be incorporated into the industry and how technological advancements could assist. 3D printed construction is a marriage of high-tech equipment and the built environment that will ultimately require a new set of skills, blending both IT knowledge and construction expertise.

For starters, Muneer foresees a new method of working in relation to 3D printing, particularly in relation to planning and design, project and commercial management, as well as health and safety. For estimators and quantity surveyors alike, when it comes to quantifying and costing projects, the fact that 3D printing relies heavily on concrete, a familiar material to the construction industry, will eliminate some measure of uncertainty.

Some aspects of the project might be simpler on a 3D printed development, given the need for volumetric calculations of concrete rather than unitised calculations of myriad parts such as blockwork, steel, and timber, as well as less labour. Quality assurance will also be of paramount concern as inspections relating to building control will need to provide a human eye that can check the work, so to speak, of an automated process.

“3D printing, as a modern method of construction (MMC) could have a transformative impact on how we build globally” Dawud Muneer MRICS, RICS

A concrete answer?

Already, there are quality assurance concerns when building with advanced robotics exposed to the elements. Andrew McCoy, director of the Virginia Center for Housing Research at Virginia Tech University, has worked on several 3D printed prototype houses. He has seen walls differ in height because of varying wind, humidity and temperature differentials – for example if one wall goes up in direct sun, versus another in the shade – and struggles to keep concrete at just the right consistency to support more weight above but also bond to the layer below. Not to mention that concrete itself is becoming a scarcer global commodity.

“I believe fundamentally in 3D printing for housing, but I don’t know that it’s concrete we’re going to be using in five years,” says McCoy.

Widespread uptake by consumers will depend on a range of factors. While a lower price point is appealing, early mass-market homes are not orders of magnitude less expensive. As of March, homes for sale in Lennar’s Wolf Ranch development outside Austin were selling for $278-298 per ft2, compared to the Austin market’s median price per square foot of $312. With its new technology unveiled in March, ICON is offering new builds at $25 per ft2 for wall systems or $80 per ft2 including foundation and roof.

Some critics point out that land acquisition, servicing sites with utilities and artificial scarcity from zoning restrictions are the primary factors in the high cost of housing rather than labour and construction costs. Finally, concrete homes cannot be renovated as easily as wood frame houses. The expression “down to the studs” does not apply when there are no studs.

“Property owners are going to ask surveyors about 3D printing as it becomes more prevalent” KP Reddy, investor

Any prospective homebuyer, meanwhile, still needs financing. If 3D printing takes off in the UK, it does hold some promise vis-à-vis other non-traditional methods. “Modular and composite construction have not been approved in terms of getting a mortgage,” says Muneer. “Because of the strong performance rating, this type of construction has a stronger chance of mortgage approval.”

Reddy, the venture capitalist, made an early stage bet that ICON could be the construction tech sector’s next unicorn. 3D printing may become the future of construction, or it may flop. But the potential is sufficient, he argues, for surveyors to get up to speed.

“Property owners are going to ask surveyors about 3D printing as it becomes more prevalent,” he says. “The right answer to an owner is not going to be ‘we don’t believe in this.’ Now is the time and opportunity for surveyors to get educated and informed.”