Illustration by Alberto Miranda

When Kath Thompson’s mother needed to find a new rental property, it was no simple process. Her mother was in her late 70s and it seemed wise to future-proof her requirements by securing a flat that was close to the amenities of Harrogate, the town in northern England where she lives. One that had a lift would also be helpful – a tough call in a town centre that is famous for its Victorian buildings.

What Kath did not expect was the number of rejections they received from letting agents who would not even allow them to view available flats. “It was obvious that my mother wasn’t seen as a desirable tenant,” says Kath. “Despite having always paid her rent on time, having great references and having enough income to cover the rent, we struggled to get a foot in the door. It was so stressful for Mum who was being forced to move as her landlord was selling her home of many years.”

It took several months to secure a new flat that was suitable and with a letting agent that would consider an elderly tenant – and even then a relative had to become a lifetime guarantor to convince the landlord.

But Kath’s experiences are not unique. “The private rented sector is a particularly difficult place for older people,” says Lisabel Miles of Age UK, the British charity that advocates for rights for the elderly. She cites a worry among many landlords that elderly people will need adaptations made to the rental properties to remain in them as well as a fear that older tenants will not be able to fund rent rises. Although age discrimination contravenes the Equality Act, it is often difficult to prove and enforcement is even rarer.

The proportion of people entering retirement as property owners is falling, however, and this is already a problem and likely to become worse if landlords are reluctant to house them. The English Housing Survey of 2022 found that only 69% of 55-64 year olds owned their house in 2021 compared with 79% in 2011. Spiralling property prices, relationship breakdowns and the rise of single-person households have all played their part in this. The survey found 382,000 households with a tenant over the age of 65 living in the private rented sector in England. But the sector accommodates nearly 1.2m households of tenants between the ages of 45 and 64. Only a small proportion of those will be able to move into home ownership or social housing before retirement.

“A lot of single older women tend to be a [vulnerable] cohort. Housing the older generation is a hidden issue here” Scott Langford MRICS, community housing group SGCH

A global problem

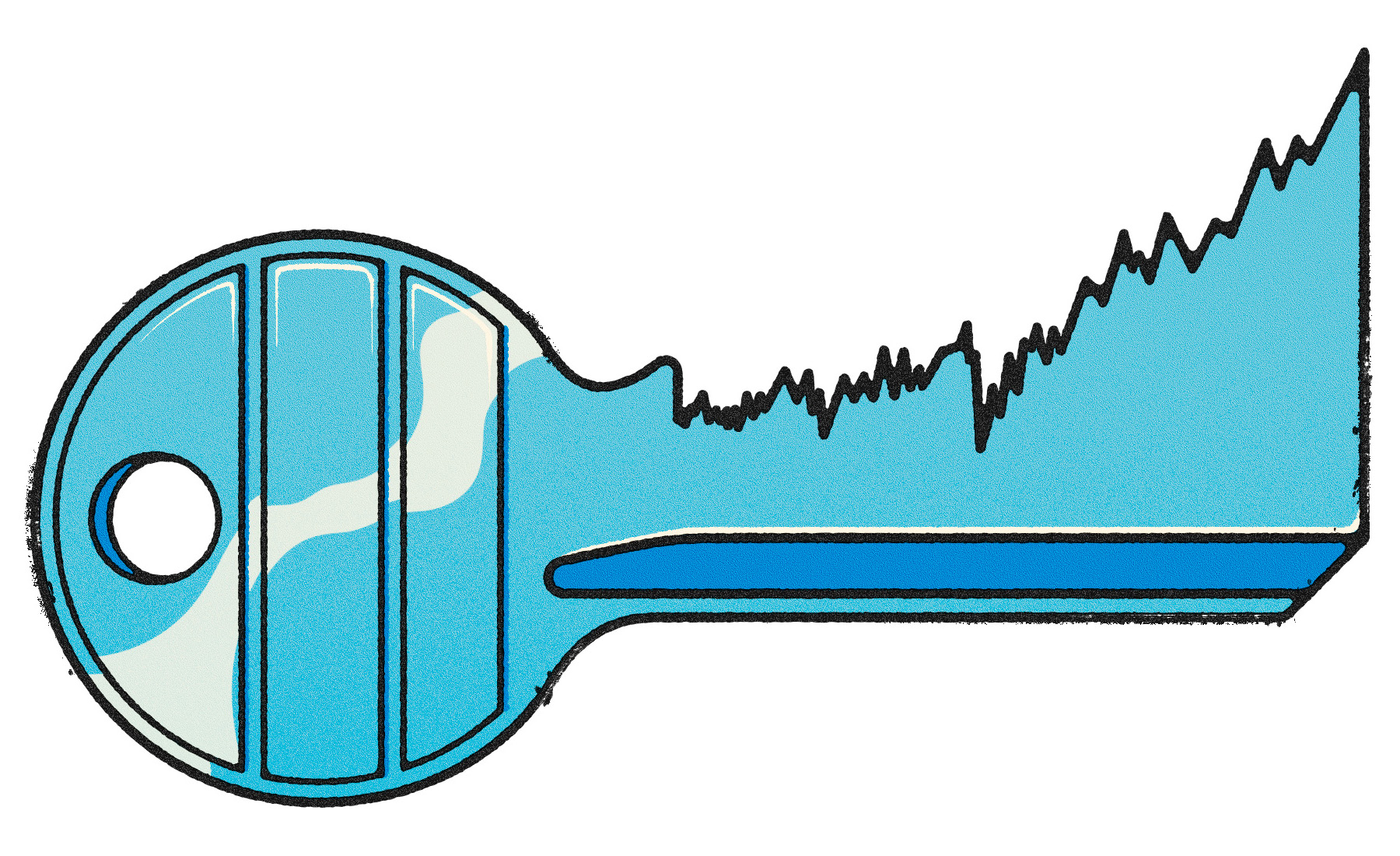

This is not just an English issue – or even a British one. Any market that has experienced a property boom in the past couple of decades is facing a ticking timebomb regarding how it will support elderly tenants. In many countries where elderly people may have once expected to stay in their rented homes as long as they wanted, the erosion of protected tenancies together with the lack of supply of social housing has made that a pipe dream.

“Since we’ve come out of COVID-19, Australia has experienced house price growth that has been extraordinary,” says Scott Langford MRICS of the community housing group SGCH in Sydney. “We’ve taken the last few years of cheap money and poured it into housing.”

An influx of people returning to the country once the strict COVID-19 protocols were over, together with a large number of wealthy overseas students choosing Australian universities, has put an enormous strain on the market. And in many of the country’s cities “the number of units being built doesn’t come close [to what’s needed]”. The result has been, in a country where owning your own home is very much part of the fabric of identity, home ownership is down to about 70%.

“The public discussion is about working households that are struggling to find or keep a home,” Langford says. “But a lot of single older women tend to be a [vulnerable] cohort. Housing the older generation is a hidden issue here.”

In March, the Demographia International Affordability Index ranked countries by their housing affordability (median house price over pre-tax gross median household income) – a score 5.1 or more is seen as “severely unaffordable”. The UK and Singapore scored 5.3; Australia scored 8.2 and New Zealand a weighty 10.8. But nowhere was close to the unaffordable might of Hong Kong which has an eye-watering score of 18.8.

“There is a dire housing shortage in Hong Kong,” says Paul Man Hong Li MRICS. As well as running his own surveying practice in the city, Li is a member of the Special Committee on Elderly Housing of the Hong Kong Housing Society, one of the largest providers of social and public housing in the region. Inevitably, in an area where accommodation is so hard to secure, the issue of elderly tenants isn’t so much hidden as hiding in plain sight.

“There is a dire housing shortage in Hong Kong” Paul Man Hong Li MRICS, member of Hong Kong Housing Society

“For people priced out of property ownership and renting private properties, there are other options,” says Li. “They can live in public housing but that is a five and a half year wait (on average) to get to the top of the list and many people end up waiting several years more. Another option is to live in subdivided units.”

Notoriously, not only is Hong Kong’s housing extremely expensive and in short supply, it is also very compact, even measured against European inner-city apartments. Li says that it is not uncommon for a family apartment of 500ft2 to be divided – with the help of partition walls – to accommodate four or even five units. “They’re not entirely legal,” he concedes, “but they’re difficult to avoid because of the lack of better alternatives.” A tenant may have to pay about HK$5,000 (USD$640) per month for one of these units.

The poverty rate among Hong Kong’s elderly is 45%, before policy intervention such as social security allowances. Leaving the crowded city and moving to more affordable parts of the mainland is rarely an option, due to language, cultural issues, lack of social support and difficulty accessing supportive resources, says Li.

And there is another issue which prejudices Hong Kong’s private landlords against elderly tenants: stigmatised property. “This happens when an unnatural death occurs in the property. The value goes down and the owner can find getting a mortgage difficult,” says Li. “It is not unusual to see a 30% discount in these circumstances.” It is understandable that landlords would want to protect their assets from this but very unfortunate for the elderly who are regarded higher risk.

A balanced property portfolio

Roger Southam FRICS is a Caribbean-based real estate consultant with 40 years of experience in the UK and US. He sounds a note of optimism about the issue. “Traditionally ‘small-time’ landlords that account for about 75% of the buy-to-let market and letting agents may have been blinkered,” he says. “But there are some very enlightened developers in many parts of the world and the multi-family homes [build to rent] market is growing exponentially. For those landlords it’s about the long-term.”

These large housing providers will want to establish a balanced portfolio of tenants, including mixed generations. It is a situation that Age UK’s Lisabel Miles would applaud. “Older people can be great tenants. They want to stay once they’ve moved in, they’re less likely to have parties or make a noise. They’re more responsible about looking after a home. We need landlords to recognise that.”