“In Grimsby we have stuck with the plan through some quite difficult times, COVID-19 being one, major inflation another, and we are now seeing a number of schemes either complete or go forward.

“It’s testament to how much resilience it takes to stick with it and keep going,” says Damien Jaines-White MRICS, assistant director of regeneration at North East Lincolnshire Council. He is describing the “hard grind” of regenerating the port town of Grimsby, which lies on the mouth of the Humber Estuary on the east coast of England. Once celebrated as the world’s largest fishing port, Grimsby has suffered the same fate as many of the UK’s former industrial towns, economic decline.

Over the last few decades, it’s become the go-to town for grim media portrayals of dilapidated, run-down places dogged by social and economic hardship. Parts of Grimsby are among England’s most deprived – it has a startlingly high crime rate (nearly 90% higher than the average in England) and low educational attainment, with 12% of its 90,000 population without any qualifications. But that’s not the whole story.

It’s also a place that has ambition. Grimsby is not only home to the UK’s largest seafood processing centre, but it’s also a world leader in offshore wind technology. It hosts Danish company Ørsted’s £14m operations and maintenance centre, servicing Grimsby’s six offshore wind farms (including the world’s largest, Hornsea) and powering 3.2m homes with green energy. “Because of our location and because of who we’ve attracted here, we’ve got a new idea of a future,” says Mark Webb, managing director of Grimsby business support organisation, E-Factor. “Grimsby has something to pin its aspirations to and I can’t tell you what a difference that makes.”

For Grimsby, a key part of realising these aspirations is regenerating the town centre and creating a place that is capable of capitalising on its economic opportunity. It’s four years into its reported £100m regeneration programme and the physical signs are springing up around the town, with most of its projects set to complete next year. But the question is, can it join places like Margate, Hull and Sheffield in regenerating its fortunes? And does it have the magic ingredients to really make a difference?

Creating a sense of place

Rewind a few years and like many places in the UK, Grimsby was grappling with how to create a 21st century town, one that was sustainable, adaptable and could serve multiple uses. Its primary focus was a shopping destination, but its high street was visibly suffering from changing consumer retail habits. Its commercial property vacancy rates were consistently higher than the national average and between 2011 and 2021 town centre footfall had dropped by 65%.

It was disjointed with parts of the town geographically, particularly its waterside, which was poorly connected. Its population was in dire need of improved employment, education and skills opportunities. Overall Grimsby lacked a “sense of place,” said its own council. But by 2020 it had both a masterplan and town investment plan, and more crucially, the ear of a government with money to spend.

The UK government had launched its £3.6bn Towns Fund to kick-start regeneration across 100 places in England. And Grimsby became its regeneration darling, attracting more than £64m in government funds. “We had unashamed ambition,” recalls Jaines-White. “We were not afraid to go down and knock on the doors of senior civil servants and ministers. We also articulated a very clear ambition for our place, focusing on what is possible.”

Since then, it’s made steady progress on its regeneration projects, all of which are built to sustainable standards as part of its economic link to the renewables industry. A new public and outdoor event space at Riverhead Square, close to the River Freshney, is complete. Down on Alexandra Dock, Projekt Renewable was opened last year. Made from shipping containers, it’s designed as the bridge between the renewables industry and the local community, providing educational and cultural events.

The town’s Grade II listed West Haven Maltings building is being redeveloped into the Horizon Youth Zone, which will offer education, sports and leisure for eight-to-19-year-olds. Next to the Youth Zone, developer Keepmoat is working with the council to develop a 6.25 acre brownfield site to create a 130-home waterfront community for the town centre. And adjacent to the town’s shopping centre, Freshney Place, land has been earmarked for a five-screen cinema, leisure and entertainment centre, which is expected to be completed by 2026.

But inevitably in a period marred by a global pandemic and an economic downturn, there have been a few bumps along the way. Jaines-White says these prompted “brave decisions”. Most notably buying Freshney Place, the largest shopping centre in Lincolnshire, for a reported £25m after it went into administration in early 2022. He says this opened up more redevelopment opportunities. But it also enabled them to locate an NHS community diagnostic centre in Freshney Place, adding a further use as a community hub. “I’m really proud of that one,” says Jaines-White, “We’ve put health in a location accessible to all and it will increase footfall, it’s a win, win.”

Sandy Forsyth, lead researcher at think tank Localis and author of regeneration report Design For Life, says there needs to be a recognition that urban areas can be very flexible, and community-driven healthcare should be at the heart of any programme. “Town centres especially can have multiple opportunities grow from them.”

She points to a similar scheme, the Dorset Health Village located in Beales department store in Poole and says the footfall of patients going into the clinic is also “rejuvenating the commercial premises in the department store and rejuvenating economic growth for the town”.

“In Grimsby we have stuck with the plan through some quite difficult times” Damien Jaines-White MRICS, North East Lincolnshire Council

Working with businesses

While Grimsby’s injection of government funding was a game changer, many see its approach to partnerships as one of its magic ingredients. E-Factor’s Webb says early on there was a real acknowledgment that no one organisation, notably the council, could do the regeneration alone. The business community set up its own ‘on the ground’ support organisation, the 2025 Group. “Most of the public didn’t believe it was going to happen,” Webb recalls. He says it was important to create a “sense of trust” and a momentum within the town. “We decided to bring every part of our network and influence to bear but only ever talk about what was actually going to happen. And that’s what we continue to do.”

These connections have also enabled many business owners to directly invest in Grimsby’s regeneration, including Webb and Ørsted, which put £1m into the Youth Horizon Zone. Webb worked in partnership with the council to apply for £1.5m government funding and matched the rest to buy St James House, a vacant building on St James Square. Work is already underway to create a business hub for the town called The Hive, which will include 20 offices, a rooftop garden and mixed-use space on the ground floor.

Webb says that while this will create vital new space for local businesses, it will also bring people to what had become a forgotten part of the town. “We’re going to bring that green back to life and make a space that is useful,” he says. “And that’s going to be key, there’s no use in investing in lovely buildings that are going to be empty 90% of the time, that does nothing for your regeneration.”

Interestingly, the town hasn’t just focused on the physical aspects of regeneration. Over the last four years it has held a number of community and cultural events, such Edible Grimsby and a Viking Parade – part of creating a sense of town pride and identity. “We’ve overlaid this with a much stronger focus on culture and heritage,” says Jaines-White. “We’ve really celebrated what’s happening in the town centre and that’s integral to it all.” Webb agrees: “Regeneration can’t just be about having buildings. Events make people engage in the town where they might not have done before. That took no buildings, just some people with imagination.”

Jaines-White says Grimsby is now the “cusp” of its regeneration jigsaw coming together and while the town has looked at what others have achieved, most notably in Sheffield, Barnsley and Stockton on Tees, it will always “plough its own furrow”. He expects the town to achieve its diversification, but the “ultimate test” will be whether people make an active lifestyle choice to live in Grimsby town centre.

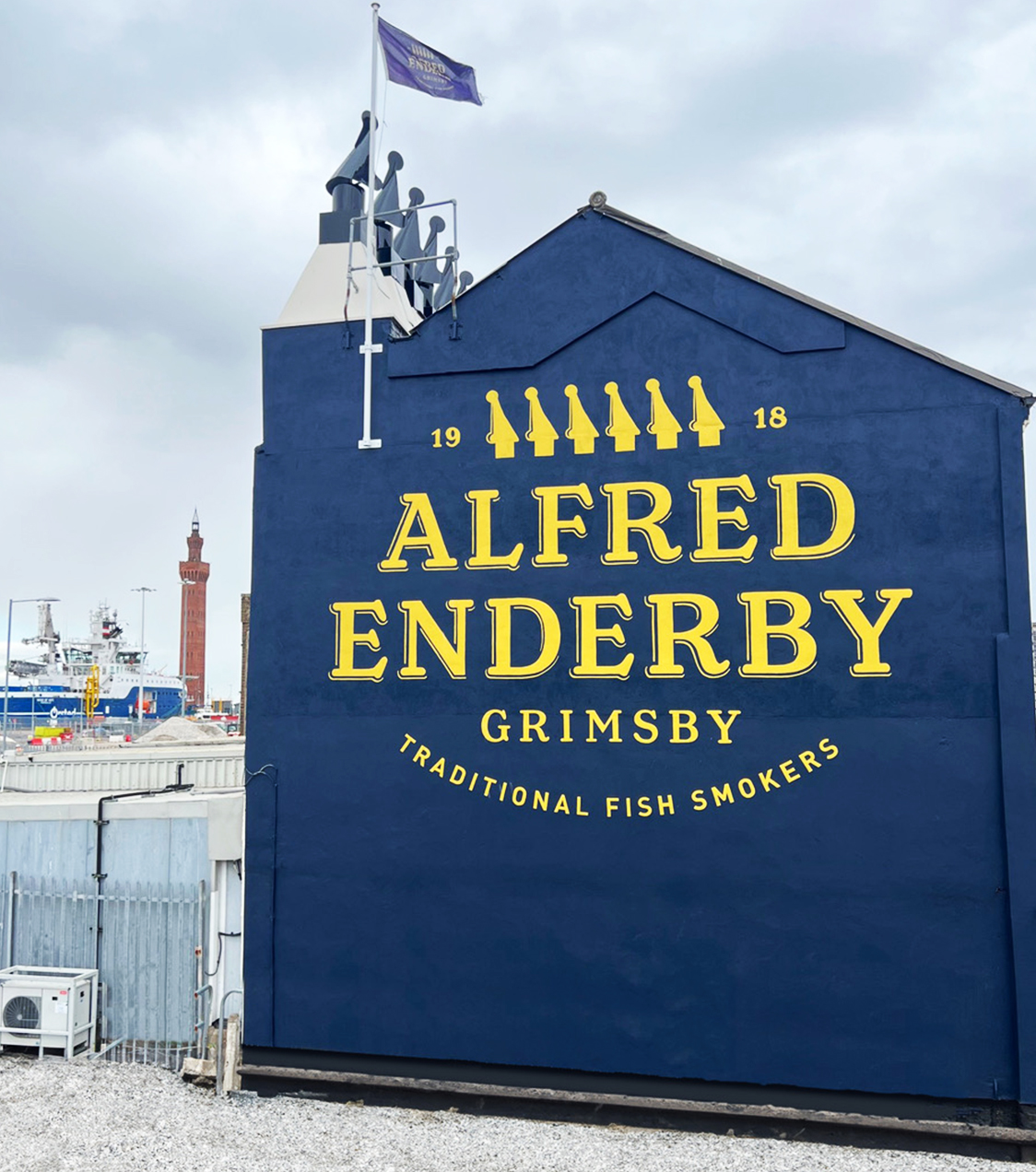

He adds: “We want to capitalise on our uniqueness. We want to celebrate the heritage that we have in our ports and seafood and we want to celebrate the future around the low carbon environment and offshore wind.”