Image by Timo Lenzen

Big tech firms face a pressing problem: how to power their ever-growing portfolios of datacentres while still meeting their pledges to reduce carbon emissions.

Recent tie-ups between the likes of Google and Meta suggest next-generation geothermal power could be a crucial element of the solution.

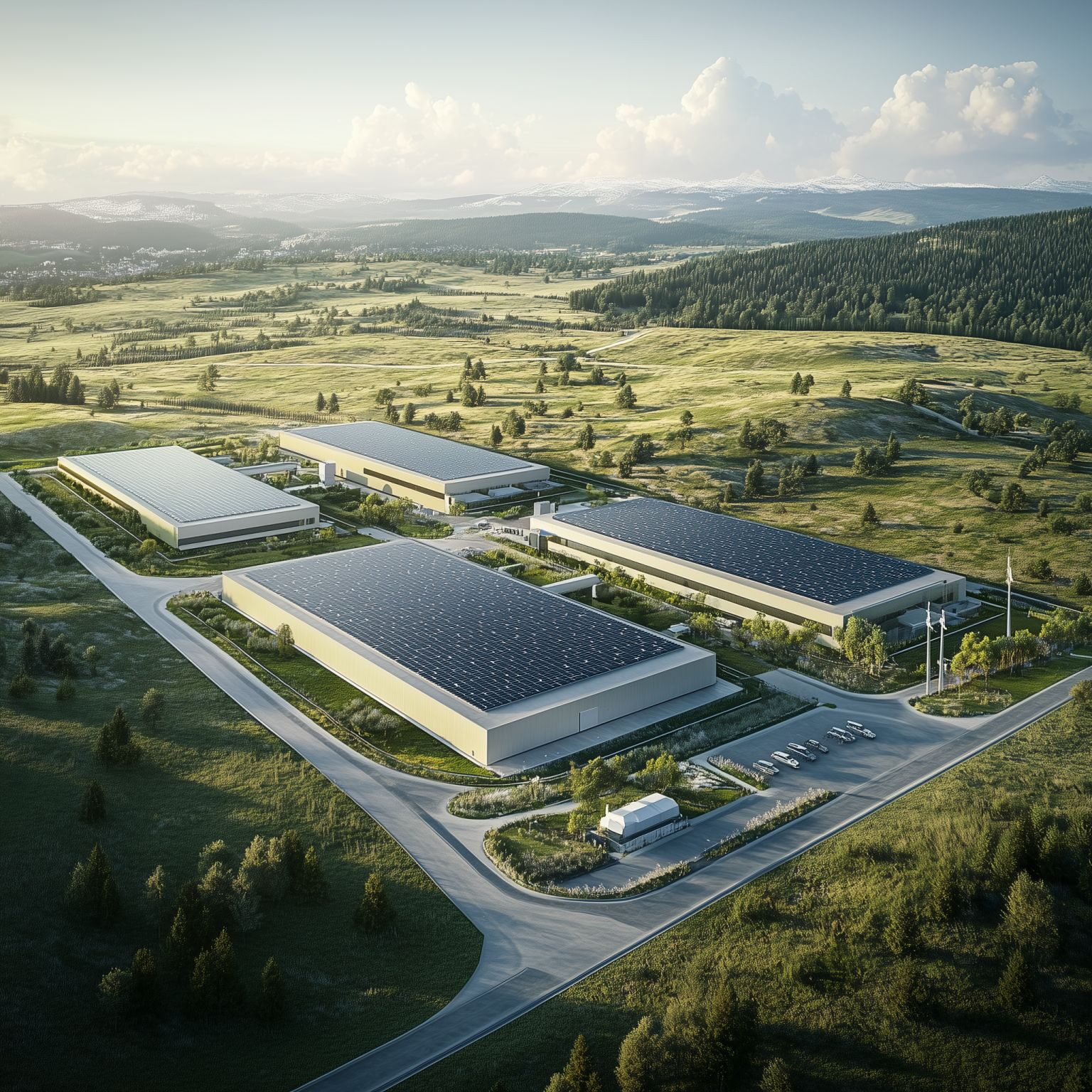

In August, Sage Geosystems announced an agreement to provide Facebook owner Meta with 150MW of geothermal power. For comparison, 1MW of electricity would be needed to meet the power demand of around 750 homes. Sage will use its Geopressured Geothermal System, which harvests pressure and heat from water stored deep underground, to provide carbon-free power to Meta’s datacentres at a site located “east of the Rocky Mountains” in the USA.

The partnership follows on the heels of the world's first corporate agreement for a next-generation geothermal power initiative, which was signed in 2021 by Google and another frontrunner in the next-generation geothermal space, Fervo Energy. Fervo’s 3.5MW pilot plant in the Nevada desert went online in November 2023, feeding low-emission electricity into the local grid that serves Google’s datacentres in the state. Following the successful test of its technology, the company has recently started construction of a 400MW project in Utah, that it expects to be online by 2028.

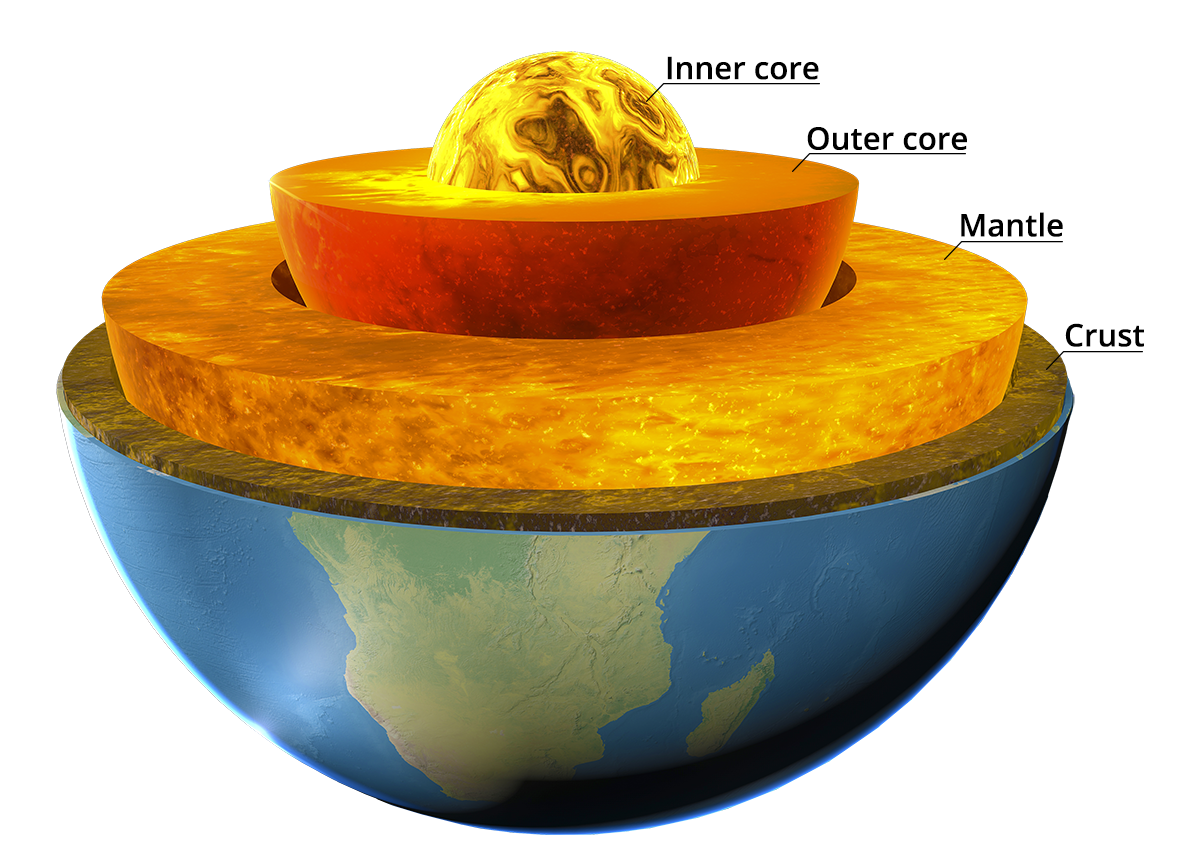

Geothermal energy generation is not an entirely new technology. But it has hitherto been viable only in the few geological regions where the heat simmers just below the Earth's crust, such as Iceland and parts of the western US. Next generation geothermal drills burrow down into areas where underground “hot rocks” are present, which are much more widespread. Using techniques developed by the shale gas fracking industry, water is pumped in to be heated by the Earth’s temperature to around 150oC, then the steam is brought back to the surface, where a turbine converts the heat and pressure to electricity.

For datacentre operators and developers, the technology represents a potential breakthrough. This is because pressure is growing for them to find affordable sources of what is termed “clean firm energy” – a steady, uninterrupted supply of low carbon power. The volume of electricity required to power datacentres has rocketed in recent years, fuelled first by the widespread adoption of cloud applications and now by the boom in datacentres used for “training” artificial intelligence (AI) applications.

Modern microchips are far more energy-intensive than earlier generations, with the consequence that server racks which once needed one to three kilowatts (KW) of electricity now require 40KW. Meanwhile datacentre buildings have got larger. Two decades ago, a typical facility would have consumed just a few megawatts at most. Today the most power-hungry datacentres require more than 100MW.

AI needs more power

Research shows that the appetite of generative AI tools for large quantities of data could mean that by 2030 datacentres will potentially consume up to 9.1% of US electricity generation annually, compared with an estimated 4% today. Other global regions are also struggling to meet demand, and in Europe some major datacentre markets have simply run out of power capacity for the industry to expand further. For example, Irish authorities have put a moratorium on new datacentres being built in Dublin until 2028.

Increasingly, decisions on where to locate datacentres are not driven by the desire to find a site close to major population centres, but by the availability of power, says Andrew Jay MRICS, head of datacentre solutions for EMEA at CBRE. “There's a mismatch between the time it takes to build a datacentre and the time it takes to build a power distribution system. If you were to submit an application for enough power from the grid to build a big datacentre in west London today, the response would come back with a date of sometime around 2038.”

The volume of funding required to meet datacentre developers’ electricity needs is an issue for US utility companies, says Dallas-based Ali Greenwood, executive director of Cushman & Wakefield's datacentre advisory group. “The scale has gotten so large – $50m to $100m to provide a substation to power a single datacentre campus – that we can't look to public utilities or the government to offset costs that are only benefiting datacentre development. It's not fair to burden residential and industrial customers with that capital expenditure,” she says.

Meanwhile, big tech firms have set ambitious decarbonisation goals. Google has committed to operate all its datacentres and office campuses on “24/7 carbon-free energy” by 2030. Meta has targeted reaching net zero emissions over the same period.

Going off-grid

The combination of power scarcity and pressure to decarbonise is driving tech giants to look at off-grid, or “micro-grid” solutions, says Jon Clark, a sustainability and ESG strategist at construction and property consultancy Rider Levett Bucknall. “They are providing their own power to sites, and if possible, providing surplus power back to the grid. We are seeing huge demand for solar and hydropower, where it is available, and new technology starting to come through like geothermal and small modular nuclear reactors.”

Hydro-electric generation is already in widespread use to power datacentres in regions where it is plentiful, such as the Nordics. Solar and wind will also meet some of the need, but because they are weather-dependent and therefore unable to guarantee a steady supply, they need to be backed up by gas-fired generators or expensive battery storage. They can also be land-hungry and unsightly.

Karine Kleinhaus, director of stakeholder engagement at Project Innerspace, a US nonprofit company formed to promote and accelerate the adoption of geothermal energy, argues that it scores more highly as a potential power source for datacentres than alternative technologies. “It's homegrown, it's resilient and it's 24/7. It's clean, and it has a small land footprint. It can feed directly into and co-locate with datacentres,” she says.

Modern drilling techniques will open up many more areas for geothermal, but how deep you have to drill and how hot it is, depends on the area’s geology, says Drew Nelson, Project Innerspace’s vice president for programmes, policy and strategy. In some places, it will still not be cost effective to drill deep enough to get to a temperature that will produce power, he admits.

Render of the Sage Meta geothermal powered datacentre

Fervo Google geothermal collaboration. Source: Google

Fervo Google geothermal collaboration. Source: Google

That means knowing the location of subterranean hotspots is crucial. To meet that need, Project Innerspace has partnered with Google to produce a global geothermal resource mapping and assessment tool, Geomap, “essentially a Google Maps for geothermal.” It collates ground temperature data produced by the fossil fuels industry, allowing landowners and project developers to see which locations have the greatest potential for a geothermal facility. In future it is also planned to include a function that maps whether existing datacentre locations have the potential to be retrofitted for geothermal.

Geothermal energy can be applied in most places on Earth, if ground source heat pumps and the use of absorption chillers for cooling is included, says Nelson. “Our analysis shows if we took the rate that we drill for oil and gas and we applied that to geothermal, we found that you could meet 77% of global projected energy demand and more than 100% of heat demand by 2050,” he claims.

In parallel, tech firms and governments are accelerating efforts to harness the potential of small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs), like those used to power nuclear submarines. Google is again at the forefront, and in October signed an agreement with California-based Kairos Power to supply six or seven SMRs, which it hopes will generate around 500MW by 2035.

Meanwhile in the UK, four companies are bidding to be selected by the government to develop SMR technology. To date both the UK and US lack a robust regulatory framework for their introduction, however, and it is expected to take several years to develop one.

“The scale has gotten so large that we can't look to public utilities or the government to offset costs that are only benefiting datacentre development” Ali Greenwood, Cushman & Wakefield

Geothermal potential in the UK

Kim Moreton MRICS, a land and resources surveyor operating as an independent European project director, recently carried out a survey of geothermal potential in the UK. He says there is an existing “rich skill base” in areas such as geophysics and deep well extraction developed in the oil and gas industries that can be repurposed for geothermal.

Identifying sites to satisfy the datacentre boom will also play into surveyors’ skill set, he argues: “They will require land referencing and geoscience skills, especially for geothermal, and the ability to interpret cost implications, investment opportunities and taxation classes. They will very definitely be involved in the matrix of assets, rights and income opportunities, particularly for the largest estates and landowners.”

With coal and gas-fired stations being wound down and datacentres’ appetite for power only likely to increase, developers and operators will look to a mixture of sources including geothermal, renewables, nuclear, and other innovative technologies like gas with carbon capture to fill the short-term gap between supply and demand.

That means it is vital to support pilot projects so that they are up and running as quickly as possible, says Nelson. “We want to make sure that as this boom in datacentres and other electricity demand happens, that that all these clean technologies, particularly geothermal, are well positioned to take advantage of it. As citizens of Earth, we need these solutions, and we need them now.”