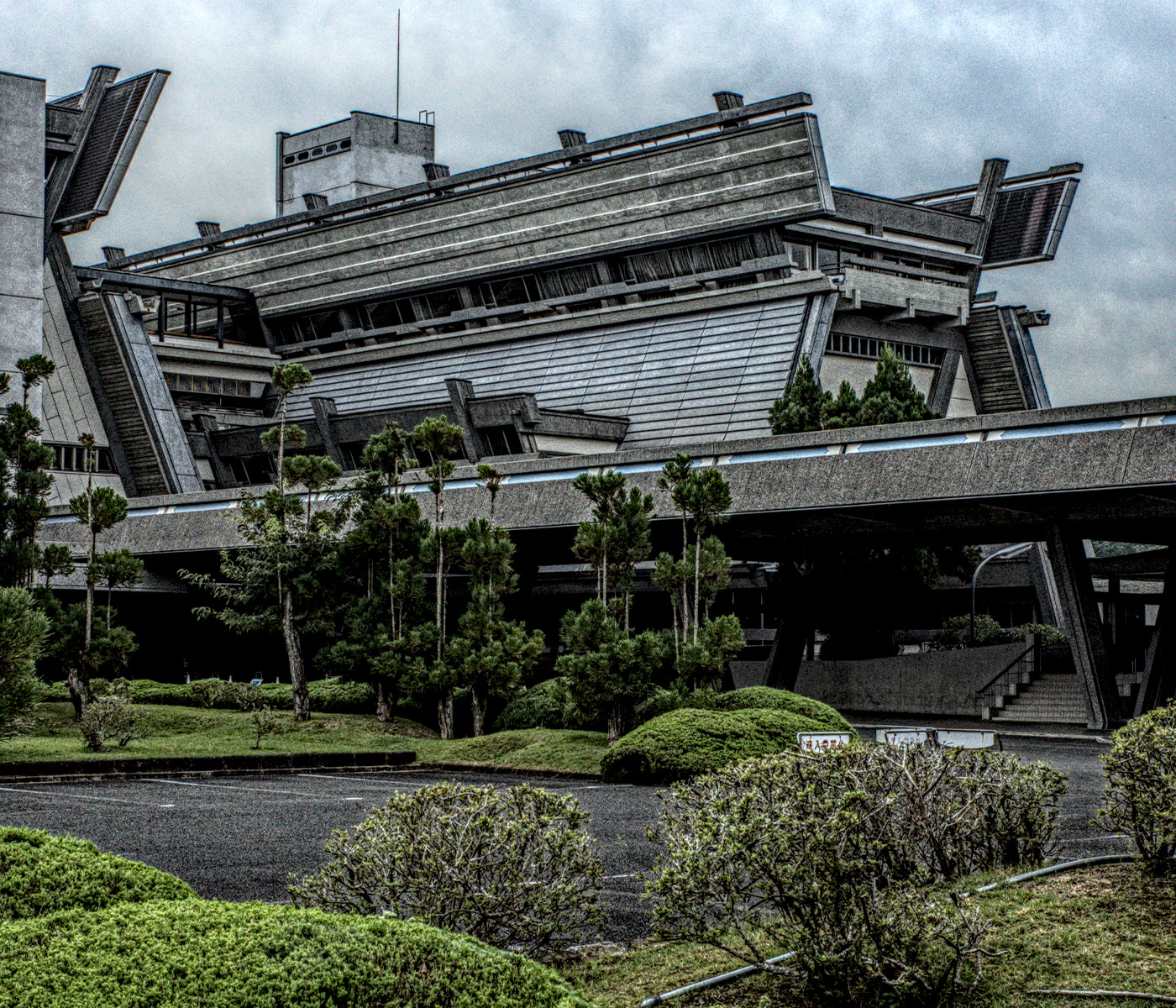

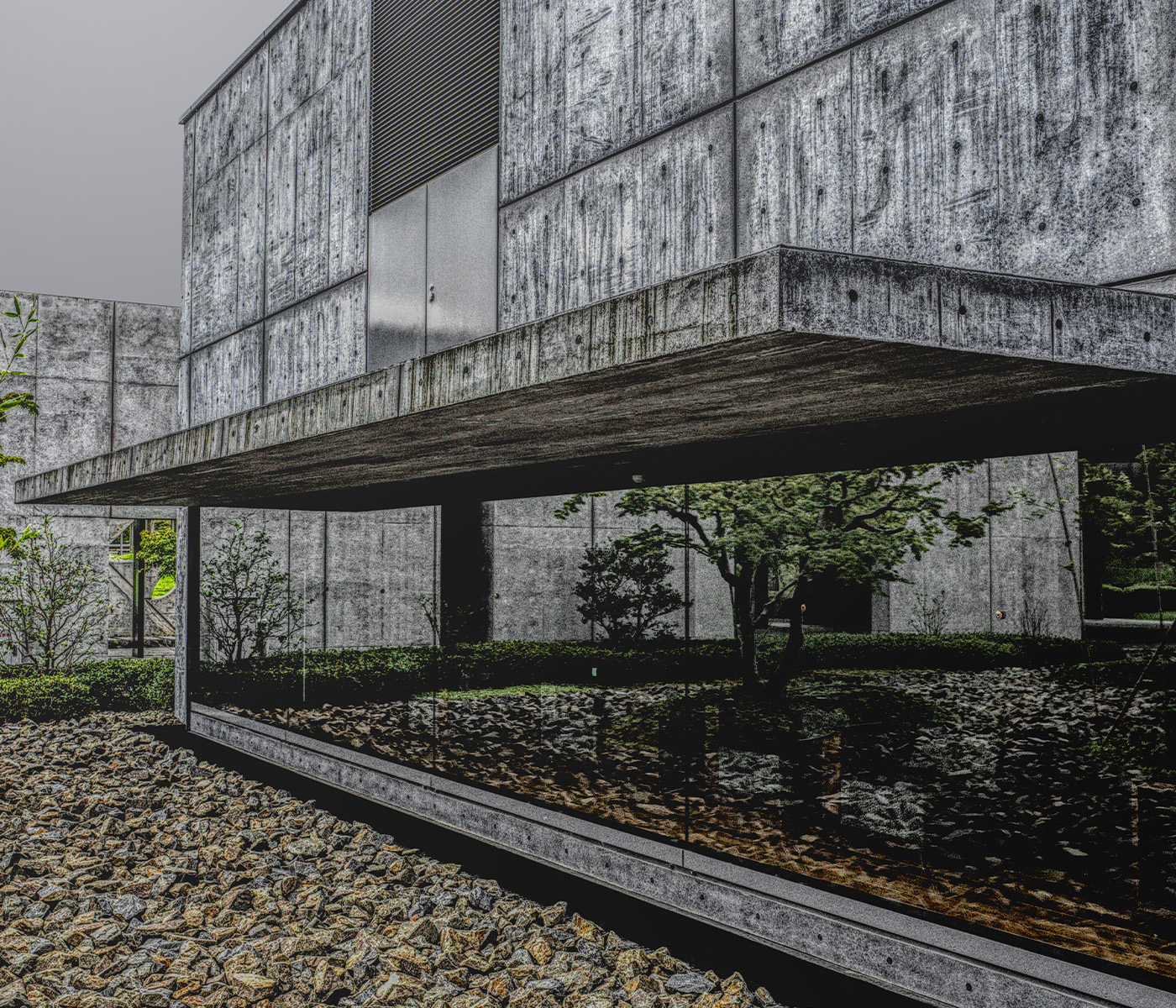

Matsubara Civic Library (Osaka), completed 2020. Photography by Paul Tulett (@brutal_zen)

Brutalist buildings with their large forms, stark exposed concrete and angular shapes have been part of many US and European cities since the 1950s. They are a symbol of post-World War Two rebuilding, which embraced the style’s low cost and speedy construction.

But the grey monoliths are also firmly part of Japanese architecture. From the Nago Civic & Meeting Hall in Okinawa to St Mary’s Cathedral in Tokyo, they symbolise the country’s evolution from wooden buildings with ornate entrances. This evolution was led by architects like Kenzo Tange, who saw the need to create large-scale functional structures quickly and efficiently.

“They were also seeking to break from the traditions of pre-war Japanese architecture,” says Paul Tulett, an Okinawa-based architectural photographer specialising in Japanese Brutalism since completing a Master’s degree in Urban Planning and Environment. “This starkness, this minimalism, was a contrast, an alternative to a more ornate traditional style. The goal of these cutting-edge architects was to build public support for new democratic institutions and civic society in the post-war period.”

At the same time the country saw another post-war style emerging, called Metabolism. These structures were seen as living organisms, developing, growing and being added to when needed.

Similarities in their timeline, in building megastructures and primarily using concrete, has fuelled debate about the fine line between the two movements, and which buildings sit in which style. Tange is also considered a leading figure of Metabolism, adding to the crossover confusion.

What both firmly have in common however, is surviving repeated calls to tear down these hulking concrete structures.

Brutalist beginnings

Today’s greener, tech dominated world was a far cry from post-World War Two Europe when British husband and wife architect team, Peter and Alison Smithson, evolved Brutalism from the style created by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier.

Brutalism’s low-cost modularity and material focus was used in institutional building and utilitarian, affordable social housing influenced by socialist principles. The architects believed their designs could help create a better, more egalitarian world. Architecture critic Reyner Banham associated it with the French phrases ‘beton brut’, meaning raw concrete, and ‘art brut’ meaning raw art.

The style spread worldwide, finding a home in Boston’s City Hall, Geisel Library in San Diego, Habitat 67 in Montreal, the Brunswick Centre in London, Jakiya Sangsad Bhaban in Dhaka and the Western City Gate in Belgrade.

While Japan also adopted this style of building out of post-war necessity, Juliana Kei, lecturer in architecture at the University of Liverpool, argues the country’s experimentation with Brutalist/beton brut buildings is parallel to or even predates the West’s.

“The Harumi apartments [in Tokyo Bay] by Kunio Maekawa can be considered an early example of Brutalism, and Maekawa worked with [architect] Le Corbusier on the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, a fine example of Brutalist architecture completed in 1959.”

In the late 1970s, Brutalism’s popularity began to decline – in part because its bleakness and connection to totalitarianism led to bad press. Being used as backdrops for dystopian films like Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange or Michael Radford’sNineteen Eighty-Four didn’t help.

However, the style has been re-evaluated in recent years. The Barbican is one of several much-loved Brutalist London landmarks and in 2015 a trio of Boston architects Mark Pasnik, Michael Kubo, and Chris Grimley wrote a book called Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston.

In Japan, “there isn’t that association with totalitarian state structures,” says Tulett. Japanese architects were influenced by modernists in Europe, but they were also influenced by traditional Japanese approaches to architecture. “It’s a give and take,” he says.

“There are similarities with simple lines, and appreciation of form. They go back to the Brutalist utilitarian function over form and how to lay things out. That intertwines with Japanese approaches to architecture that have been around for eons.”

And this is where Brutalism and Metabolism in Japan have been categorised similarly. “The two have common methodologies of giving a clear form to each function and expressing them in the external appearance,” says Tatsuo Iso, author of Brutalist Architecture in Japan. “I do not see ‘brutalism and ‘metabolism’ as existing independently of each other.”

Brutalism versus Metabolism

“The architectural movement in Japan is said [to be] Metabolism rather than Brutalism,” says Aki Kageyama, managing director and principal at Akihisa Kageyama Architects in Tokyo. He adds that Team X and Metabolism had a similar concept with style and “trying to change world by their work”.

Team X (or Team 10) was a group of 1950s architects, whose stated ideal was to arrive at “meaningful groups of buildings, where each building is a live thing and a natural extension of the others.”

The Metabolism poster building, demolished last April, was the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Toyko. It featured 140 capsules plugged into two cores, or as some critics labelled it, “a tower with washing machine units stuck on”. Another often used example is the Kyoto International Conference Center.

Metabolism treats a building as an organic entity that can be added to and evolve with changing needs, says Tulett: “Brutalist design does not consciously incorporate the notion of later addition. Metabolism and Brutalism happened to come about in Japan around the same time, around the 1960s, when there was rapid industrialisation. The economy was transforming quickly and there was so much new technology coming in.”

He does concede “there is overlap” but, “Metabolism’s organic form can be seen mainly from the outside, while Brutalism's adaptability seems internal.” This adds to the latter’s environmental credentials, making a plausible case to save the ageing creations.

Many Brutalist buildings have been pulled down including the five-storey former Karasuma Church in Kyoto, built in 1971 and demolished in 2019. In February, it was announced Tange’s 1960s-built Kagawa Gymnasium in Takamatsu would be razed, because its structure is not earthquake resistant and its ceilings are too low for certain sports competitions.

Brutalism goes green

Even though Brutalism is viewed as “concrete, monolithic and rigid, the interiors often have flexible layouts,” says Tulett, giving the example of the Japanese tradition of sliding doors easily separating rooms. “A lot of Brutalist architectural designs have a changeable layout, especially public institutional buildings. It’s just very open,” he adds.

The buildings are “proving to be very adaptable throughout their longevity, says Tulett. “They are ripe for renovation projects. Rather than tear them down … they are very much set up for urban agriculture, roof top greening and repurposing.

Their preservation would be very much in line with the ethos of Pritzker Prize 2021 winners, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal: “Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform and reuse!”

Plans to preserve Brutalist architecture aren’t without their obstacles though, says Iso: “Brutalist architecture is a strong reflection of the social conditions and building techniques of its time. It is therefore well worth preserving and passing on to future generations.

“However, it is difficult to make a case to refurbish a building if it is found to be unable to meet the performance requirements of the modern day.

“If concrete columns are widened to increase their earthquake resistance the proportions of the space will change dramatically, inevitably taking away from the original architectural qualities. There are some ingenious ways of retrofitting to prevent this, but the cost will be higher.”

Additionally, he says, as Brutalism is a widespread architectural style: “It would be unrealistic to try to preserve all the buildings in large numbers. I believe it’s important to encourage the preservation of the best of them though.”

Fans of the style

The Japanese Brutalist masters have clearly left their mark, yet whether all their masterpieces will survive is still uncertain. What is happening is something of a renaissance and love unexpectedly coming from a new generation of video gamers. “A lot of younger people are getting into Brutalism because it reminds them of backdrops in the video games they play,” says Tulett.

His own personal love for the style comes from its, ‘honesty and raw aesthetics’, and rings true for his 120,000 followers on his Instagram account, @brutal_zen. “People say there’s no colour, but I love the way it weathers if left unadorned, unpainted. People say it’s got no character, but I must disagree. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder but understanding builds appreciation.

“If you understood the incredible skill required to construct these 'monsters', you'd love them too.”