Photography by Peter Landers

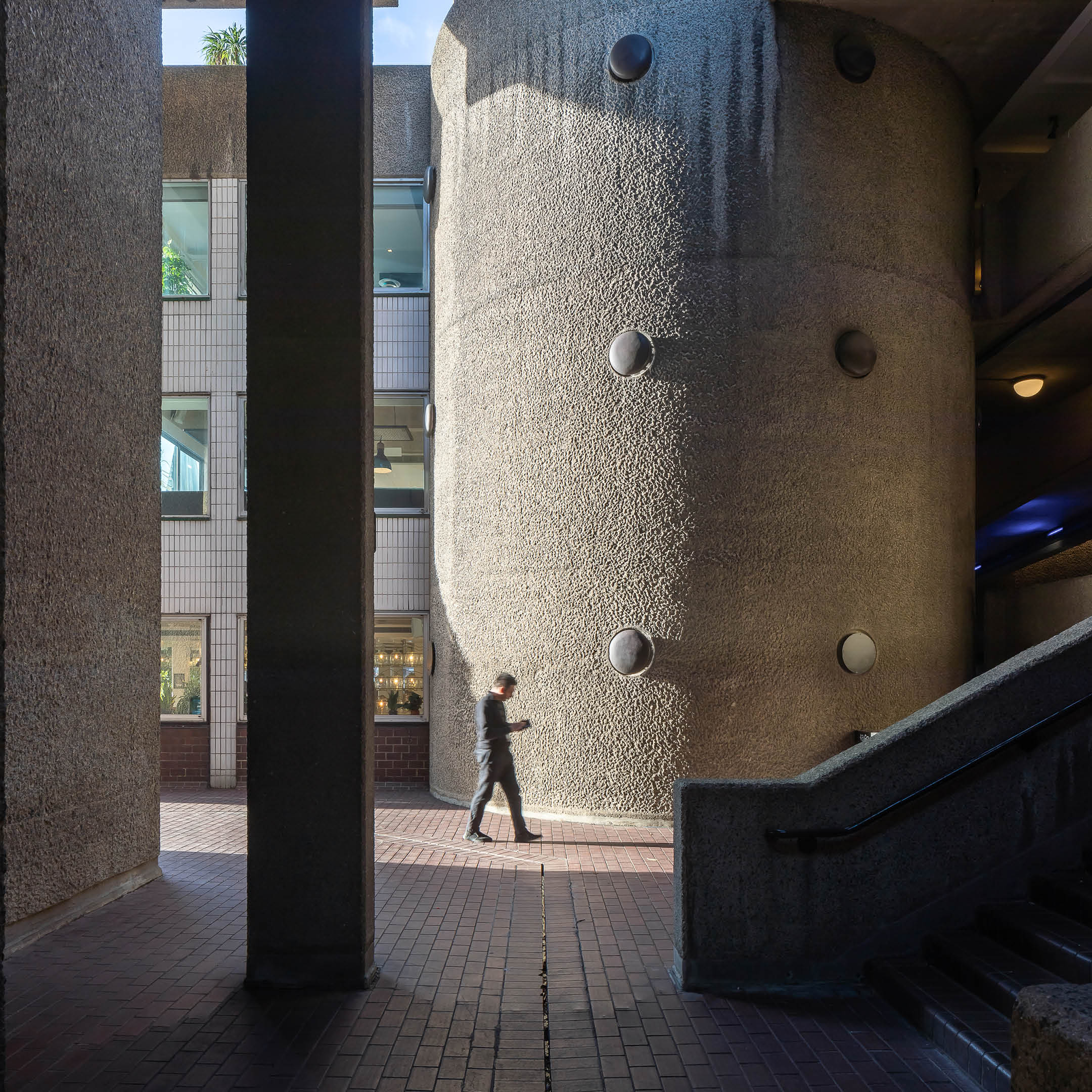

The Barbican Estate is an instantly recognisable brutalist development of 2,000 flats in central London and contained within it is one of the country’s foremost arts venues, the Barbican Centre.

There is a common misconception that the Estate began life as council housing in 1969, however it was always intended to be a profit-making venture for the City of London Corporation. The target market was senior-level city workers who lived in the suburbs – these modern, well-located rental flats meant they wouldn’t have to endure the grind of the daily commute.

To lure potential residents back to an area that had been virtually flattened during the Blitz, the Barbican Estate offered a range of amenities. These included a lakeside terrace, library, on-site school and of course the Barbican Arts Centre (although that didn’t officially open until 1982). In many ways, it was an early example of the 15-minute city concept.

Lakeside terrace

Barbican towers

“It is only really in the last two decades that Brutalism has found a new fanbase” Jon Astbury, The Barbican

Initially, plans for a post-war development on the site were for commercial use but one of the motives for a residential development was boosting the dwindling population of the City of London constituency. In the mid-1800s, the population of the parish of St Giles Cripplegate (now the name of the church in the Barbican Estate) was more than 13,000 but by 1951 it was just 28 and the City of London was in danger of becoming a modern-day ‘rotten borough’.

“[Architects] Chamberlin, Powell & Bon were invited to pitch for the Barbican scheme having already worked for the City on the adjacent Golden Lane Estate,” says Jon Astbury, assistant curator at The Barbican. “A group called the New Barbican Committee sought to reframe the City of London as a place where relatively affluent, white-collar workers would want to live.”

Sports facilities and green space within the Barbican Estate

Bold concrete creation

“At the time, the use of what were more commonly considered unattractive, utilitarian materials such as concrete was very popular among the architectural avant-garde, but had little appeal with the public,” says Astbury. “If anything, it was looked on even less favourably by the time the Barbican [Centre] opened, and it is only really in the last two decades that Brutalism has found a new fanbase.”

There were, however, some major advantages to building with concrete on such a large project. Simeon Wilkie, an assistant scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute who specialises in historic concrete structures, says: “Concrete is relatively cheap when compared to many other building materials. It is a versatile material that can be poured into a variety of geometries … and can be used to construct large-scale projects relatively quickly.”

He also argues that the Brutalist style of the Barbican may have seemed controversial simply because it was so different to anything else being done at the time. “When compared to other architectural styles which came before it, Brutalism is very plain,” says Wilkie. “It lacks the decorative ornamentation of earlier styles such as Art Nouveau and Beaux Arts, and the colour palette of Art Deco. The fact that concrete is grey also doesn’t help – even Aberdeen with all its granite buildings is divisive for this reason.”

And the way we look at Brutalism now has been influenced by popular culture, he adds: “For almost 60 years, Brutalism has been used to represent dystopian societies and authoritarian regimes in movies, TV and comic books – this may have led to a negative association.”

“The fact that concrete is grey also doesn’t help – even Aberdeen with all its granite buildings is divisive for this reason” Simeon Wilkie, Getty Conservation Institute

Medieval church

In the middle of the Barbican Estate is St Giles Cripplegate church, which dates back to 1090. It’s one of London’s few remaining medieval churches and one that, despite several fires over the course of its history and losing all its furniture during the Blitz, remains an active church to this day.

“Despite the reputation of Modernism for rejecting historical styles and buildings, St Giles was embraced and reinterpreted as part of a town square at the centre of the Barbican site alongside the remnants of the old city wall,” says Astbury. “This area is also where there are some of the strangest elements of the Barbican’s design, such as tombs and gravestones incorporated into the new areas of high-walk around the lake.

St Giles Cripplegate Church

“The sheer scale and ambition of the Barbican makes it so unlike anything else to be found in the UK or even Europe” Jon Astbury, The Barbican

Time for renewal

It’s 54 years since the first residents of the Barbican Estate moved in and the Barbican Centre celebrated its 40th birthday last year. Despite having several decades on the clock, the Centre is in good shape, says Astbury.

“My understanding is that because the Barbican is built primarily from exposed, high-quality concrete with little to no exterior treatment, the appearance of the building has held up extremely well. Chamberlin, Powell & Bon went on extensive tours to countries like Sweden and Norway to determine the best means of casting and the best aggregate to use for the concrete.”

Architects Oliver Heywood and Asif Khan are co-leading the Barbican Renewal project that began last year. It aims to renovate parts of the Barbican Centre and offer new benefits for everyone using or visiting the Centre. Heywood agrees that the building has handled the test of time well but could do with some attention.

Exterior of the Barbican Centre

“The concrete has stood up well, but it’s suffered from a lack of maintenance,” he says. “You see it everywhere you go around the Estate if you’re looking for it. Over time, a lot of the mastic in the movement joints in the concrete has deteriorated, so there’s water leaking through those joints in the frame. The maintenance team has rigged this system of drip trays that run underneath the joints and connects to a mini drainpipe conduit. They’ve had to think creatively over time.”

“This is the first time in the building’s history that someone has looked at it holistically like we are,” says Heywood. “There have been projects over the years that have been localised responses to a specific issue, but this is a chance to zoom out and look at a masterplan for the next 40 years.”

Khan adds: “We have an indication of what the Centre needs to be able to serve the community around it. It doesn’t just have this evening economy, it’s something that can be better used during the day and become a major facility for the area.”

The outside of Frobisher Crescent and the Barbican Conservatory

A much-loved part of London

Heywood and Khan are both keen to stress that while the Barbican Renewal project does intend to overhaul the infrastructure and facilities of the Arts Centre, changes to the exterior will be minimal.

“When you tell people you’re working on the Barbican Renewal project, the first thing they say is ‘I love the Barbican,’” says Khan. “And the second thing they say is ‘Don’t mess it up!’ We’re in that camp too, we think it’s one of the greatest cultural institutions in the world and one of the most important assets London has. We want to give it a new lease of life.”

But what is it about the Barbican Estate that makes it so unique and provokes such a protective reaction from people?

Lakeside terrace at night

Barbican cinemas

Modern office buildings surround parts of the Barbican Estate

“We think it’s one of the most important assets London has” Asif Khan, Barbican Renewal project

Modern walkways connecting Barbican with the new surrounding office blocks

“The sheer scale and ambition of the Barbican makes it so unlike anything else to be found in the UK or even Europe,” says Astbury. “Empty sites of this size in such central locations do not come along often, and nor does the combination of wills to transform them so completely. I think the fact that it is such an oasis in which every detail has been designed and considered is what visitors cannot help but be drawn to, whether they find it visually attractive or not.”

The word ‘oasis’ is one that comes up a lot when reading about the Barbican, as if its designers managed to carve out a little piece of central London that offers a moment of tranquillity away from the city’s hustle and bustle.

“For me, the thing that always takes my breath away is the lakeside terrace and that feeling of being away from the city, away from everything in this calm environment,” says Heywood. It’s the closest version of a modernist utopia that I’ve experienced.”

“For me, the thing that always takes my breath away is the lakeside terrace” Oliver Heywood, Barbican Renewal project