Featured above: Old Bridge Mostar, Bosnia & Herzegovina and Hungarian Parliament Building, Budapest, both European UNESCO sites

Recent data released by UNESCO shows a startling imbalance in the geographical spread of what it classes as World Heritage sites.

There are now 1,199 sites that the United Nations body has declared are of “outstanding universal value to humanity”, since the inception of the programme in 1972.

These range from areas of stunning natural beauty covering millions of hectares to the entirely man-made, which can cover just a few square metres, such as the Holy Trinity Column of Olomouc in the Czech Republic. But nearly half (47%) of the sites are found in Europe and North America.

World heritage sites in these regions include many of those most closely associated with the designation: Roman and Greek archaeological ruins and historic city centres renowned for their beauty such as Venice, Bath, Florence, Cordoba and Bruges. Italy alone has 58 sites.

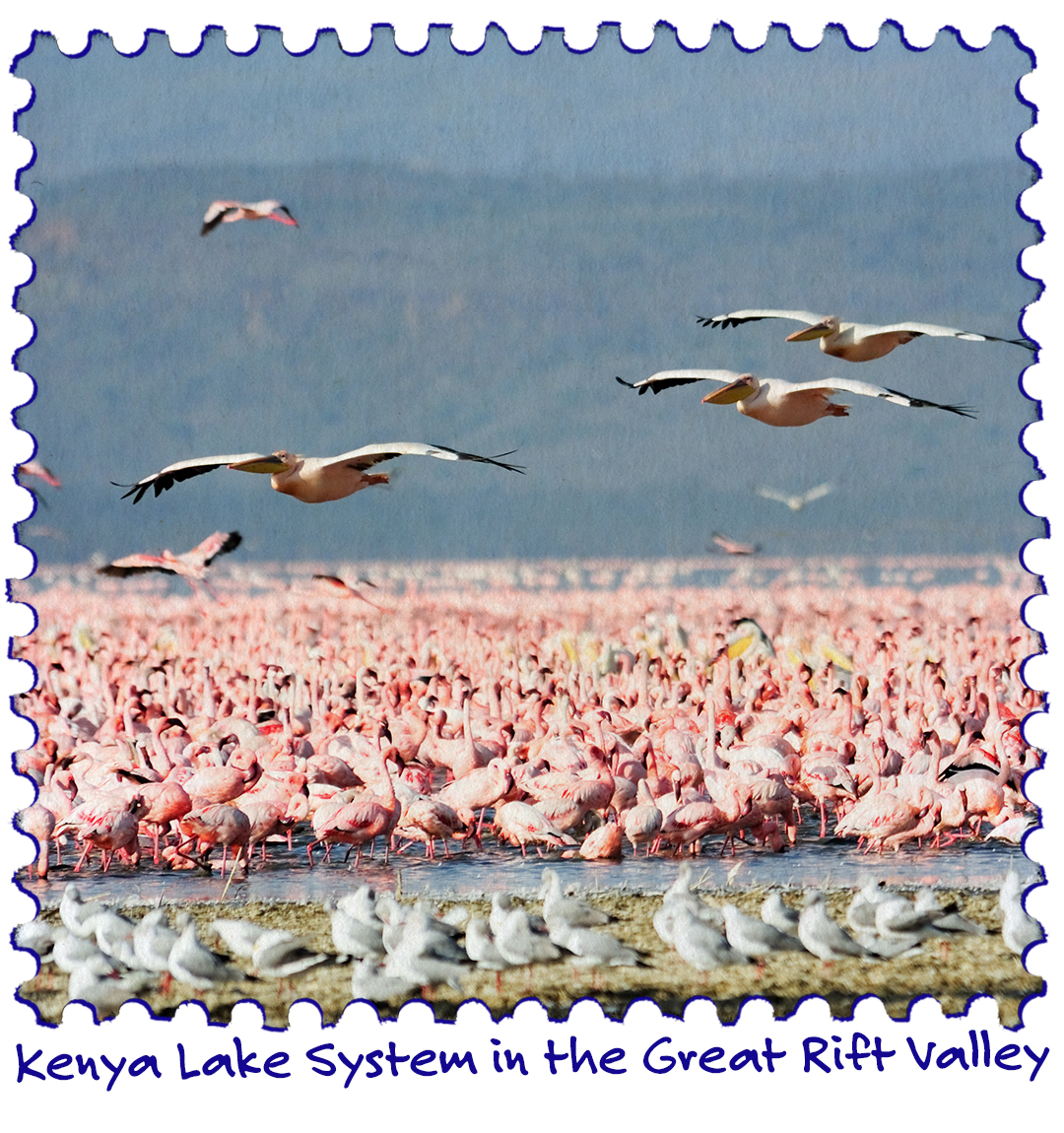

Meanwhile Africa, which has a similar landmass to Europe and North America, has only 8.5% of the world’s sites. Of those, about 40% are natural sites, compared to Europe and North America’s 565 sites which are overwhelmingly cultural (86%).

Kenyan archaeologist and professor of Heritage Studies at the University of Mauritius, Dr George Okello Abungu, has been outspoken about the paucity of UNESCO designations in Africa. "The process is too Eurocentric,” he told Deutsche Welle. “African countries have to prove the extraordinary value of their sites to humanity through a Western perspective in order to make it onto the list.”

Not everyone would state this opinion as bluntly, but it is hard to escape the uncomfortable truth that there may be some Eurocentric bias when considering which places receive UNESCO’s stamp of authenticity. After all, even among the few dozen African sites of cultural heritage, several, such as Mombasa’s Fort Jesus, Cote d’Ivoire’s Grand-Bassam or Ghana’s collection of forts and castles, are relics of European colonial activity rather than indigenous African monuments. It's a similar story in Latin America and the Caribbean, where the European-built centres of cities such as Quito, Lima, Cartagena, Willemstad, Georgetown and Santo Domingo are among the most visited.

But are there other reasons that might account for the concentration of designations within Europe and North America and their relative scarcity in the rest of the world? Perhaps there are factors at play which show, if not explicit bias, a tendency to make it much easier for Western countries to have their sites listed.

Just don’t want the designation

One thing that everyone agrees upon is that a UNESCO listing brings a site attention. There are tourists – known as ‘World Heritage baggers’ – who specifically arrange their travel around visiting as many sites as possible. And travel writers often use a UNESCO designation as the centrepiece of an article about a destination.

But that attention is not always welcomed by the residents who live near a World Heritage site. An influx of visitors may have short-term benefits for some locals but, unless carefully managed, neighbourhoods – and even entire cities in some cases – can be overwhelmed, leaving locals feeling pushed out.

Having witnessed the problems that over-tourism and over-preservation has caused – one journalist coined the term UNESCO-cide to describe it – it’s not impossible to imagine a scenario where authorities and heritage organisations decide that the costs outweigh the benefits and prefer to keep a site under the radar.

Financial implications of making an application

High among these dissuading factors is cost. While some imagine UNESCO works like a Michelin Guide, sending an anonymous team of inspectors to comb the globe for wonders before choosing the very best, it is, in fact, up to member countries to make the case for their own heritage sites. And make that case hard.

Warren Adams MRICS, the land use control administrator for Montgomery, Alabama, is involved in an application by the Georgia State University World Heritage Initiative to inscribe 13 sites associated with the civil rights movement.

This includes the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church in Montgomery, at which Martin Luther King was, for many years, the pastor. The original application for the UNESCO’s consideration was lodged in 2008 and has been added to the organisation’s tentative list.

“It’s a huge honour to be considered for inscription. It draws on the significant impact the civil rights movement had, not just here but throughout the world,” says Adams. “The application process really does require a lot of support. I don’t know what the overall cost is – especially as this application deals with 13 different sites in different municipalities – but I spend time on it, there are a lot of meetings and additional research. I would imagine it is a fairly significant cost, but the time I’m putting in is justified.”

A DCMS report from 2007 put the cost of steering a British monument or natural asset towards UNESCO inscription at between £420,000 and £570,000, which would pay for specialist staff to progress the application, consultants and marketing. This figure will undoubtedly have grown in the intervening years. But it’s likely that heritage designations rank far down the list of competing priorities in countries which do not have generous tourism and cultural budgets to fall back on.

Not able to preserve monument or environment

One of the most significant areas of concern to UNESCO is the number of world heritage sites that are classified as “in danger”. Part of the application process involves making extensive promises about the preservation of the site itself and the surrounding area in which it sits.

“We need to make sure that any future development respects the importance of the site,” says Adams of the Dexter Avenue church which sits in Montgomery’s downtown district.

While there is no doubt that he and his colleagues are very focused on treating these tentative sites sensitively, a UNESCO listing can be seen as a potential brake on development. This is because authorities that are seen to breach their commitments to preserving the “context” of the sites can be punished by the humiliation of delisting.

Liverpool’s waterfront was stripped of its UNESCO listing in 2021, because of to the local authority’s decision to develop the area in a way that UNESCO observers felt was detrimental to its historic integrity. However, Steve Rotheram, mayor of the Liverpool city region, called it a “retrograde step that does not reflect the reality of what is happening on the ground.” He added that it was “a decision taken on the other side of the world by people who do not appear to understand the renaissance that has taken place in recent years”.

“The application process really does require a lot of support… I would imagine it is a fairly significant cost.” Warren Adams MRICS, City of Montgomery

Similarly, Dresden had a referendum in 2005 to decide whether to build a new road bridge within a UNESCO world heritage site – infrastructure triumphed over conservation and, in 2009, when the bridge was completed, the city lost its listing. The Al Wusta wildlife reserve in Oman was delisted in 2007 after the habitat that protected endangered Arabian oryxes was developed for oil exploration. The Bagrati Cathedral in Georgia was also delisted in 2017 after a radical restoration although a monastery on the site remains listed.

In many countries, the need to develop areas takes precedence over the desire to conserve monuments and wildlife – particularly when a UNESCO listing comes with onerous obligations but little in the way of grants to offset them.

Instability and conflict

Parallel to authorities in the global south being unwilling or unable to make copper-bottomed guarantees around the preservation of sites as they develop, the twin threats of war and climate change make these sites even more precarious.

The vast majority of sites designated as “in danger” are in Arabic or African countries and include Palmyra which was partially destroyed by ISIS in 2015, while nearly all Syria’s other sites have suffered during its protracted civil war. Roman sites in Libya have been the target of looting and vandalism since the overthrow of Gaddafi in 2011. In Mali, civil unrest and political instability threaten three of the country’s four sites. Civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo makes it near-impossible to manage the country’s natural assets such as Garamba National Park, Kahuzi-Biega National Park and Virunga National Park.

Elsewhere, climate change is the culprit. A UNESCO report from 2021 estimated 60% of its sites were threatened by climate change (although not all these have been added to the in-danger list). Chief among these are, of course, natural assets such as the 50 world heritage sites that include glaciers or the many forests damaged or destroyed by drought or wildfires.

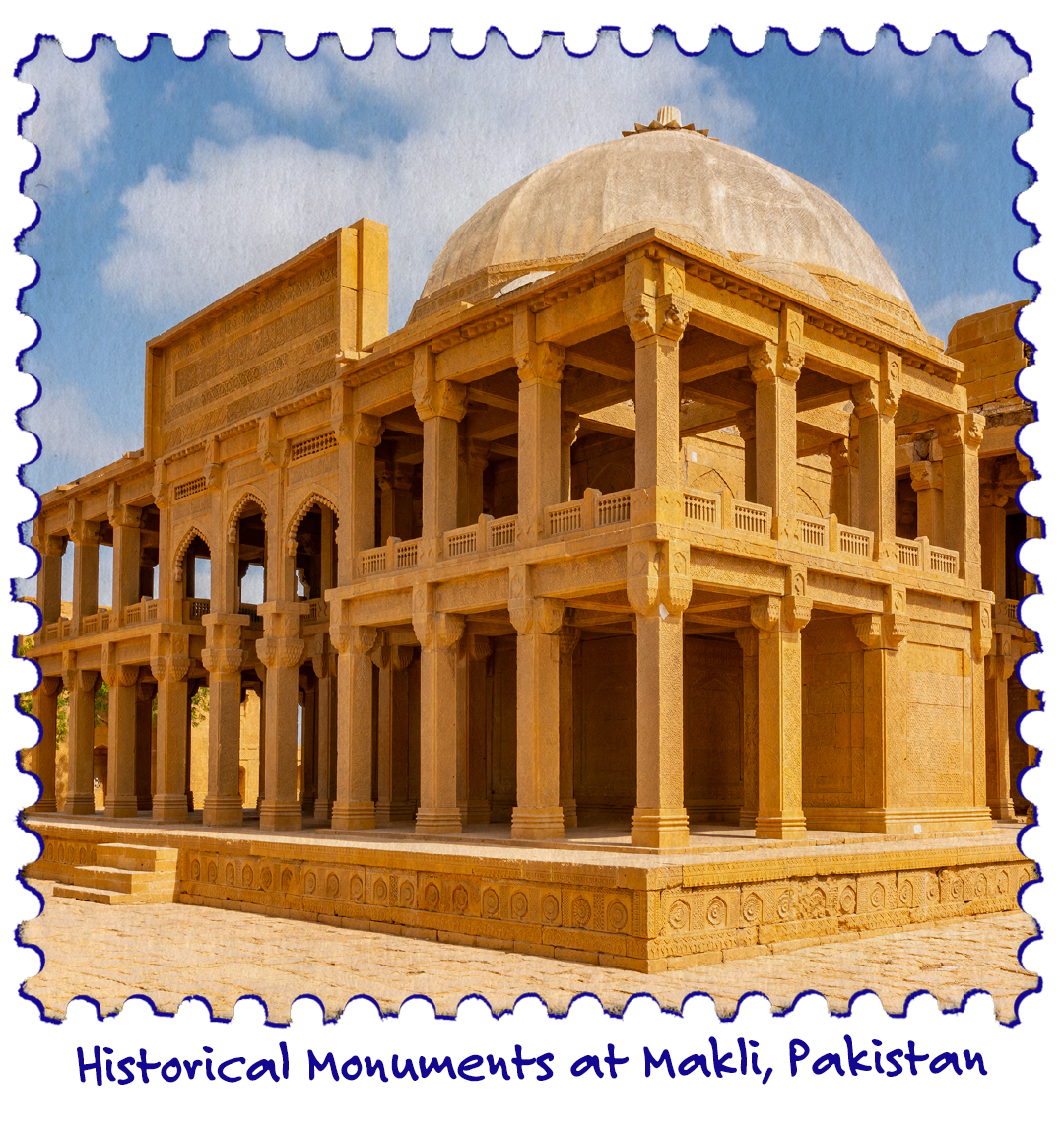

But it’s not just natural sites that are being affected: the famous statues of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) are being eroded by stronger, wetter winds; Kilwa Kisiwani in Tanzania, a collection of 12th century ruins, is also under thread of coastal erosion. In Pakistan, the historic monuments of Makli were damaged in the 2022 floods.

Bureaucracy

The sheer amount of report-writing and form-filling that goes into a successful application is a daunting pile of paperwork. The path to inscription requires five main steps, each divided into several sub-sets which need coordination and interdisciplinary oversight.

“Now we’re on the tentative list, the next step is to prepare the list of requirements including a management plan,” says Montgomery’s Adams. “UNESCO want to know how the site will be conserved, how it will be protected, how we will deal with increased tourism, how the site’s story will be told, how we will interpret its history, how the setting will be maintained.”

Once a site has been inscribed, there are regular reports to be submitted to update UNESCO. It is an onerous task and, without enthusiasm, a solid budget and a clear benefit, it is easy see why it would not be a very attractive process.