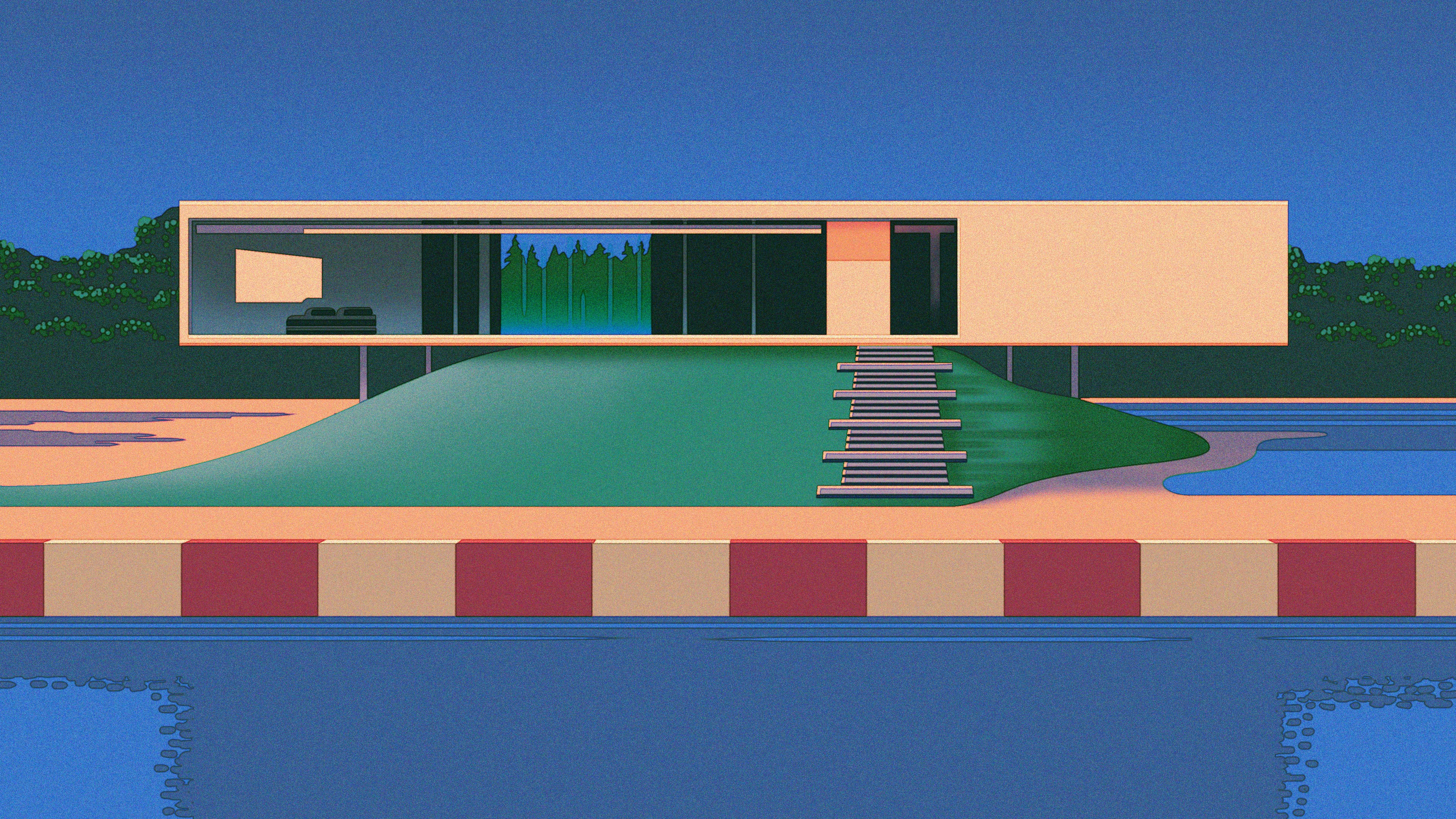

Qunli Stormwater Park, Haerbin City, China. View towards the north-east. Photo courtesy of Kongjian Yu/Turenscape.

Governments and built environment professionals are doing a lot of thinking about how our cities can adapt to cope with rising temperatures. There is, however, another issue that has thus far attracted less attention: urban water management.

As the recent devastating floods in Pakistan demonstrate all too clearly, the danger of climate change comes as much from severe rainfall as it does from extreme heat. The floods in Germany last year provide another potent example – they represent the worst such disaster in the country for decades. So, what is to be done about the situation?

While in many European nations the focus on how to adapt cities to cope with increased rainfall is a relatively recent phenomenon, in China it has been actively investigated for at least two decades. The country’s leading authority is generally held to be Kongjian Yu, president of Turenscape and founding dean and changing chair professor at Peking University’s College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture.

He has long made the distinction between grey and green infrastructure. The former includes ever bigger flood defences and run-off channels, depending on vast quantities of concrete – one of the most carbon intensive products on the planet. Green infrastructure, on the other hand, involves working harmoniously with nature.

“The alternative is nature-based solutions and nature based ecological infrastructure, which is critical for securing your ecosystems. Such ecological infrastructure has to be planned and built across scales: national, regional and local.”

Sponge cities

Yu refers to this as the ‘sponge city’ concept. “Its philosophy is to retain water, slow down water and be adaptive to water, which is totally opposite to the conventional solution of grey infrastructure,” he said. “Sponge cities are inspired by ancient wisdom of farming water management.”

More recently, international consultancy Arup put out a report entitled Global Sponge Cities Snapshot, which seeks to raise awareness of natural solutions to increased rainfall. “It’s all about trying to highlight the importance of cities moving beyond just concrete solutions to managing heavy rainfall,” says Tom Doyle, senior consultant at Arup, who worked on the report and is using it as the starting point for further academic research.

“The aim is to start conversations, encourage more cities to better quantify their natural resources and start thinking about them as assets and as infrastructure they should protect and enhance.”

The study looks at seven major cities around the world, examining their ‘sponginess’ based on three primary factors: the demands on blue and green space in the city; the hydrological properties of the soil; and the water runoff potential for the green areas.

“We then combined land use analysis with insights on the soil and types of vegetation, which allows us to estimate how much rainwater the city could absorb in heavy rainfall events. We tried to use a range of cities in different parts of the world with different urban profiles.”

Of course, some places came out of the study better by dint of their natural environment - there is little, after all, that authorities can do about the soil upon which their cities are built. The way in which urban areas have evolved over time is another critical factor. Cities with large areas of green space and plentiful lakes and other waterways are naturally more prepared.

However, Doyle says the report provides a useful starting point. “It’s a good indication of their baseline, which is a crucial first step to building a plan for enhancing their nature-based infrastructure,” he says. “And from there, cities can create ways to enhance and increase their green infrastructure.”

Simple solutions

While often difficult in terms of land ownership and cost, many of the solutions themselves are far from revolutionary. “It’s things like adding more parks, trees, greenery. Natural drainage to increase the city’s absorbency and make it more flood resilient,” says Doyle. “The benefits include cleaner air to breathe and habitats for escaping the heat.”

Naturally enough, installing such features is simpler when building a city from scratch, as has happened apace in China in recent years. It is far more difficult in existing metropolises. New York, one of the subjects of the Arup report, springs to mind. For all its wonders, the Big Apple is relentlessly urban – especially on Manhattan.

Even in such an environment, however, Doyle says that a lot can be done. “In heavily urbanised areas, the solutions often involve retrofitting blue and green infrastructure, as we’ve seen quite a lot recently in Brooklyn and Queens,” he says. “New York has probably implemented thousands of these green infrastructure solutions over the last seven years, but it still pales in comparison to the amount of impermeable space in the city.”

“Natural drainage increases the city’s absorbency and make it more flood resilient” Tom Doyle, senior consultant at Arup

Necessity is the mother of invention

One country that has better reason than most to think hard about increased rainfall and rising sea levels is the Netherlands. As anyone who has ever flown into Amsterdam must have noticed, it is incredibly vulnerable. It is no surprise that the country is rather ahead of the game, according to Floris Boogaard, professor at the Research Centre for Built Environment NoorderRuimte at Hanze University of Applied Sciences, Groningen.

“There are a lot of things you can do - technically, everything is possible,” he says. “In the Netherlands, we have over 10,000 locations [where we have made interventions], whether that is storing rainwater and trying to infiltrate it into the ground or measures from floating homes to bioswales.”

The idea of creating more absorbent cities may be relatively new to some countries, while others have been thinking about the issue for decades. Certainly, there is no shortage of solutions out there for those with the inclination and will to learn.

“There are a lot of things you can do, whether that is storing rainwater, floating homes or bioswales” Floris Boogaard, Research Centre for Built Environment NoorderRuimte