The historic address of 55 Oxley Road in Singapore is forever ingrained in Simon Monteiro’s memory for the house that is no longer there.

Built by French missionaries in the 19th century, before being converted to a gallery, the building was demolished and replaced by a more commercially viable condominium block. “It's sad it was ripped down, because it was beautiful,” says Monteiro, an associate vice president at List Sotheby’s International Realty, Singapore.

But on a landmass of 240 square miles with 6m people – London at 607 square miles, is 2.5 times larger, with 8.8m people – development land is precious. “We don't have much space in Singapore, whether we like it or not,” says Monteiro. He was one of the first to identify the commercial value of Singapore’s heritage buildings, after a developer he was working for bought 100 shophouses in the late 1990s. “I fell in love with these old buildings,” he says.

Dating back to the 1840s, shophouses reflect Singapore’s multicultural roots, that include colonial-era institutions and religious sites. “They serve as a reminder of Singapore’s history, anchoring identity in a city that’s always evolving,” says Leonard Tay, head of research, Knight Frank, Singapore.

He adds: “These buildings have architectural and artistic value, showcasing Art Deco and Anglo-Malay styles.”

A row of colourful shophouses in Singapore

A shophouse sits in front of a modern high rise building

More than 7,200 properties have been given conservation status in 100 conservation areas and today they are held in high esteem by a generation that embraces its past of immigration, trade, colonial influence, and local adaptation. The buildings have become tourist magnets, and some, like the shophouses, are so sought-after by savvy investors, they have emerged as their own asset class.

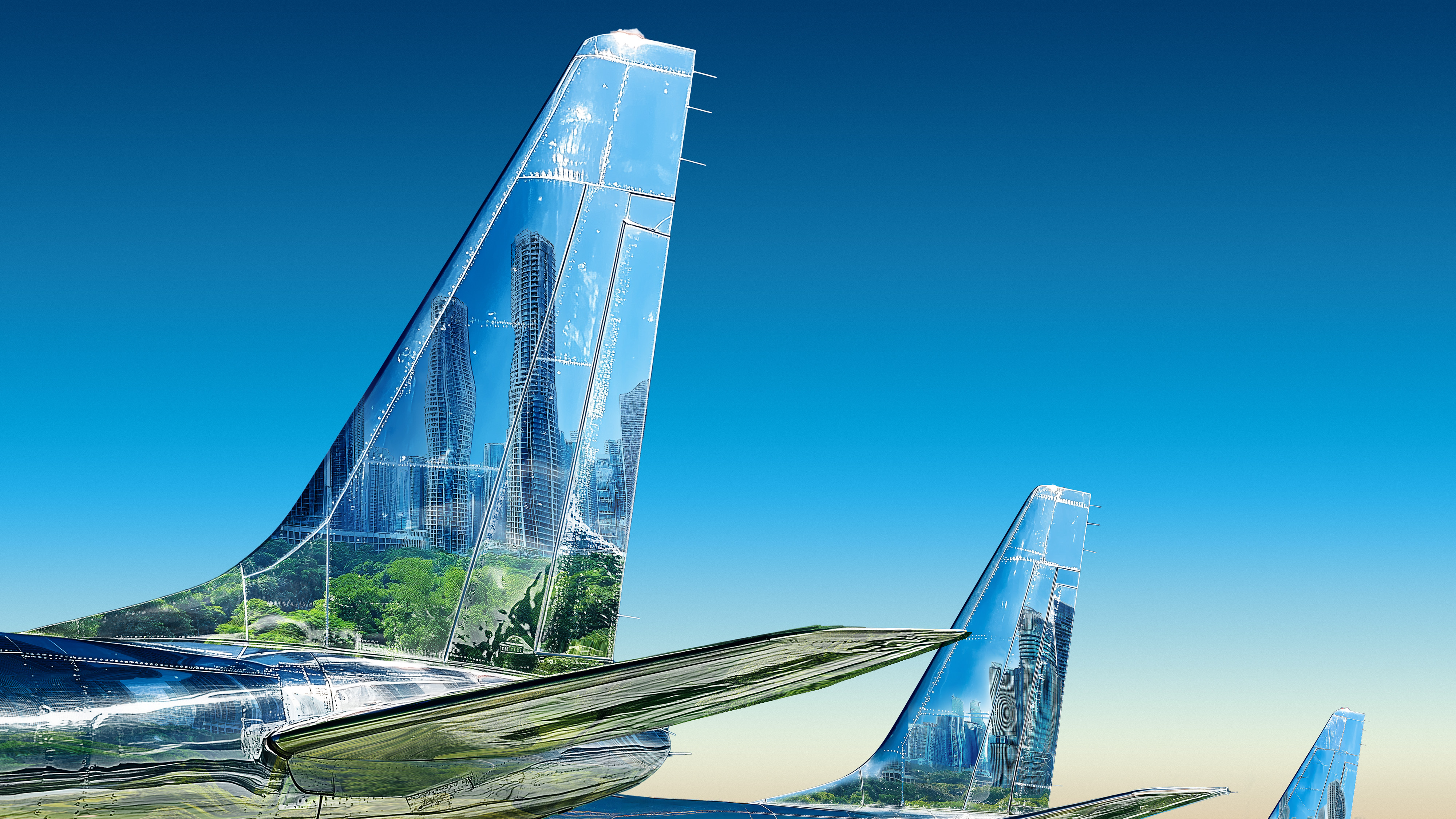

When it comes to old-meets-new, east-meets-west dynamics, a skilful balance is played in preserving older structures, surrounded by 21st century skyscrapers that have come to define Singapore’s glittering skyline, such as the instantly recognisable Marina Bay Sands.

The Ministry of National Development and the Urban Redevelopment Authority work with building owners and relevant stakeholders to identify properties of high architectural, cultural, social and historical significance. And the Singapore Land Authority (SLA) are involved in the management of the land and state properties – preserving, restoring and maintaining buildings when they are earmarked for conservation.

“Transforming heritage buildings requires collaboration with public agencies, industry players and non-profits,” says Colin Low, former chief executive of SLA (from 2021 to April 2025).

Guided by its vision of ‘Limited Land. Unlimited Space’, SLA’s mission is to unlock value in the approximately 11,000ha of state land and 2,600 state properties it manages, some of which are heritage buildings.

“[We] ensure state properties are put to meaningful use,” says Low. “Either in their original use or increasingly, adapted for new ones which give the buildings a new lease of life.” He highlights the Chinatown Smith Street rejuvenation, where shophouses are being transformed into creative lifestyle, retail, co-living and co-working spaces.

Smith Street in Chinatown, Singapore

A shop in Chinatown, Singapore

Smith Street, Chinatown, Singapore

Smith Street, Chinatown, Singapore

The rapid growth of newly formed Singapore

To gain recognition among newer developments, heritage buildings had to overcome initial neglect and destruction in favour of rapid economic growth and development when the city-state formed in the 1960s. (Having first gained independence from Britain in 1963, then Malaysia in 1965.)

Initially, freedom was not easy. Made up of the 30-mile-long mainland island, Pulau Ujong, and 62 smaller satellite islands, Singapore suffered high unemployment, poor infrastructure, and a housing shortage.

The mission of the Singaporean government, led by the country’s first Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, was to transform the country from an underdeveloped nation into a world class country and economy. Even if that meant tearing down its past.

“There were things more vital to the economic future of Singapore, so older buildings were demolished. They made some sacrifices” says Bill Jones FRICS, former RICS Governing Council member and client director of SBM Management Consultants for Real Estate, Singapore.

Despite the economic push, Lee Kuan Yew was thoughtful about the future of older buildings “because they're our past, our built heritage and they differentiate us from other places due to their beauty,” says Jones.

These include national monuments such as Raffles Hotel, Thian Hock Keng Temple Chinese temple, Sultan Mosque, and conserved buildings like Fullerton Hotel and The Arts House, formerly the Old Parliament House. Then there are the shophouses and the black and white houses.

Raffles Hotel, Singapore

Interior courtyard of Raffles Hotel, Singapore

“There were things more vital to the economic future of Singapore, so older buildings were demolished. They made some sacrifices” Bill Jones FRICS, SBM Management Consultants for Real Estate

The Arts House, Singapore

The Fullerton Hotel, Singpore

Sultan Mosque, Singapore

Thian Hock Keng Temple Chinese temple, Singapore

Investing in the shophouses

Constructed between the 1800s and the early 1920s, black and white houses were originally for municipal uses. With around 600 still surviving, they are mostly managed and preserved by the SLA and are often leased to the expat community as private homes, although some have been converted into leisure uses.

Shophouses are the most commercially transacted buildings, originally built as merchant homes and located in prime city-fringe areas of Tanjong Pagar, Chinatown, Kampong Glam, and Joo Chiat.

Known for their traditional Chinese architectural style, and continuous verandas, they are usually two to three-storeys with the ground floor commercial, and upper floors, residential or office space.

Their limited supply of just 6,500, combined with the potential for being mixed-use, and exemption from Additional Buyer’s Stamp Duty, makes them attractive to foreigners. The ability to own the entire structure, including land, has made them magnets for investors.

Monteiro says in 2005 he was buying shophouses for around S$385 per ft2. In 2025 they are S$3,800 per ft2 and now have their own asset class.

However, the allure of shophouses has also been their downfall. In August 2023, the Singapore Police Force broke a money laundering scheme by Chinese suspects, seizing cash and assets worth around S$2.8bn that included shophouses. The unprecedented scandal caused a slowdown in the shophouse market, as a spotlight was shone on regulatory measures within the sector.

“We don't have much space in Singapore, whether we like it or not” Simon Monteiro, List Sotheby’s International Realty

A detached black and white house

Terraced black and white houses

Valuing and sustainability

Valuing heritage buildings in Singapore is tricky, says Monteiro. The square footage price is not based on land, but on height due to the lack of information available on the buildings. “The government does not give you the total area,” he says. “They only give you the land area.”

Alvan Ng, associate at Singapore Realtors Inc, says doing valuations is “a numbers game” based purely on a commercial and capital standpoint and how much rent can be achieved. “But for shophouses, the rental value does not compare to the price it sells for,” he says.

Buyers are still willing to pay large sums of money for commercial use however, because “there is an irreplaceable heritage value of the property that appeals. You can't price it in terms of numbers, but people still purchase over and above the actual commercial value,” says Ng.

Given the high costs involved, shophouses can be marketed discretely, sometimes off-market, with surveyors working behind the scenes, managing buildings, doing renovations and maintenance. “It's not very transparent,” says Jones.

The biggest issue with heritage buildings can be water problems, says Ng. “Obviously, because these are old, there needs to be a lot of maintenance. Part of a critique of Singapore conservation is that it is very surface level because the government only requires that you keep the façade.”

One potential area opening to surveyors is BIM. In recent years, the National Heritage Board has been working on developing digital twins. “There could be some opportunities for BIM modelling for building, and surveying,” says Jones, adding, “they capture the history, and technical aspects of the building, which makes it easier to manage and track.”

Meanwhile, for older commercial buildings not considered ‘green’, owners need an ESG consultant to help them assess which areas to upgrade, says Alan Cheong, executive director at Savills Singapore. That consultant can also assist in applying to the Building and Construction Authority to get green certification.

Raffles Place, Singapore

Shophouses in front of modern high rise buildings

High rises behind Chinatown, Singapore

High rises behind Chinatown, Singapore

The old and the new

Older buildings in Singapore are not just for selling; they are often integrated into new developments or remembered in newer developments.

Butterfly House, a colonial home at 23 Amber Road, earned its moniker for its wing-like shape and stands as an example of “partly repurposing, partly keeping the heritage, but losing some of it at the same time,” says Jones. In 2008, developers clipped the wings, to build a condominium complex, preserving only a fraction of the street-facing façade.

At Raffles Place, Singapore’s first commercial area, the entrance of the eponymous MRT station features a façade that pays homage to the old John Little Building – the city-state’s oldest department store dating to 1842, that stood near the site until 2016. Meanwhile, the National Gallery Singapore has merged the former Supreme Court and City Hall buildings, integrating modern glass and steel, with the pre-existing colonial architecture.

It is a recognition of the importance buildings from bygone days have to the city-state’s tourist industry, that in 2024 drew 16.5m visitors. “Adaptively reusing historic buildings safeguards our cultural heritage and allows them to serve as valuable assets for tourism and economic growth, attracting visitors to the surrounding areas,” says Low.

The house at 55 Oxley Road was once a tourist draw in its incarnation as a gallery. Although long gone, the reasons why it was knocked down are accepted: “It was all about progress: getting rid of the old and doing the new,” says Ng, adding “but Singapore is a very young nation. As the society develops, it learns to value culture.”

And that means the heritage buildings will always be an integral part of Singapore’s future, just as important as the skyscrapers that have come to define the city-state.