Our celebration of significant buildings which have changed the course of architecture - and given their homes a worldwide recognition - has taken us all over the globe. From the inside-out splendour of Paris's Pompidou Centre to the iconic appeal of Sydney's Opera House, we explore twelve locations of special significance - plus three where the historic building fabric is under threat.

New York’s Little Island

Built on the site of a derelict pier, the 2.4-acre island floats above Manhattan’s Hudson River supported by 132 concrete stilts. Designed by Thomas Heatherwick and completed in 2021, the undulating landscape of the tiny park “engages the full range of senses” according to Rosalind Tsang of architectural practice BDP. “You feel a disconnection from the density and hectic pace of the city – you gain perspective. It is a moment of reflection and restoration.”

Kuala Lumpur’s Petronas Twin Towers

A modern interpretation of Islamic forms or futuristic spaceships, the 88-storey skyscrapers connected by a “sky-bridge” dominate Kuala Lumpur’s cityscape. The Petronas Towers not only represent “the future of the country but [their] location in the prime region of the city hub is a testament to the cultural diversity that is Malaysia and the possibilities waiting to be unleashed,” says Foo Gee Jen, managing director of CBRE.

North Wales’s Portmeirion

From the 1920s onwards, the architect and landowner Sir Clough Williams-Ellis salvaged architectural bric-a-brac to create his own surreal interpretation of a Tuscan Renaissance town on the Welsh coast. “The Planning Act hadn’t been thought of when he was building most of Portmeirion,” Meurig Jones, the site’s location manager. “Imagine going to the planning committee now and saying you want to put your fireplace on the front of an old building. It wouldn’t happen.”

Paris’s Pompidou Centre

The inside-out building at the heart of the city’s 4th arrondissement and its arts scene, the Pompidou gave Paris an uncharacteristic blast of modernity and fun when it was built in the 1970s. “The Pompidou Centre is a game changer. Not necessarily for the originality of the idea but because a city had the audacity to build it,” says Chris Harding, chair at architect firm, BDP. “It is wonderfully impractical - causing further debate and rolling of eyes.”

Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront

The sprawling Victoria & Alfred harbour redevelopment almost single-handedly regenerated a historic but overlooked corner of the city, turning a run-down site into an attraction that brings 24million visitors a year. The V&A Waterfront “should be seen as an urban intervention rather than a single development,” says Francois Viruly FRICS of the University of Cape Town. “It has been acclaimed as one of the world’s most successful waterfront redevelopments.”

Paris’s Grands Ensembles

Elegant and progressive post-War interpretations of social housing, les Grands Ensembles have been allowed to deteriorate over recent years. “Low-cost housing cannot be a side dish, it should punctuate the city,” declared one of its architects, Ricardo Bofill. “It provides all the elements we need to produce a city; mixed use brings a vibrancy”

Titanic Belfast

Not just a museum, but a whole quarter configured out of the old shipyards where the infamous liner was made. The 2012 building at its centre is a collection of dramatic angles which conjure up some of the scale of a ship’s hull – breathtaking. “Generally, things tend to become ‘iconic’ over a period, rather than starting that way,” says Paul Crowe, managing director at TODD Architects. “The design adopted was a leap of faith and unlike any other building in Northern Ireland.”

Chicago's Sears Tower

The world’s tallest building for the final quarter of the 20th century, the Sears Tower is a marvel of engineering innovation. “Part of [the retailer] Sears’ DNA was ‘bigness’,” says architecture journalist, Blair Kamin. “Architects … were able to convince their clients to go for the world’s tallest building title because it was great publicity for Sears – and it was great for Chicago because all of the sudden, we were number one!”

Sydney's Opera House

A roofline redolent of the sails of galleons, oyster shells or, as the critic Clive James put it, like nuns in a rugby scrum, the Sydney Opera House is far more than a concert space, it’s an instantly-recognisable landmark. “[Architect Jørn] Utzon’s sketches reference billowing clouds over the ocean, floating curved forms over a linear plinth and a floating Chinese pagoda roof,” says Philip Vivian, director of Sydney-based Bates Smart architects. “A unique expression on the end of a peninsula surrounded by a water.”

Miami's Atlantis

A post-modern apartment building that became synonymous with the revival of Miami (the city was the US’s murder capital when the Atlantis opened in 1982), its design included a dramatic five-storey palm court punched through the façade.

Birmingham's Bullring

Covered in 15,000 metal disks, this sinuous, space-age building has come to define modern Birmingham, completely side-stepping expectations of what a shopping centre should look like. “It’s a building that continues to evolve,” says Robert Bentley of Benoy architects, the practice that reimagined for the Bullring. “They created an icon that Birmingham could then rally around and promote itself on.”

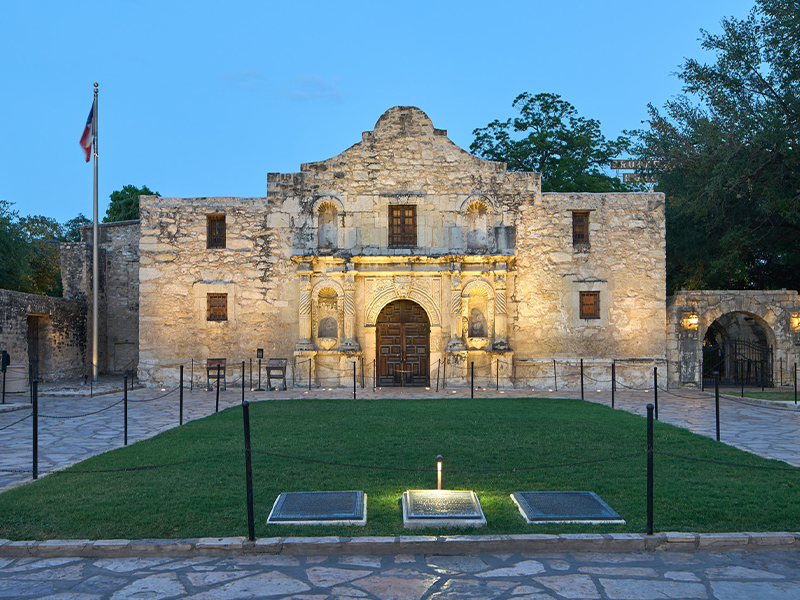

Texas's Alamo

Site of Davy Crockett’s last stand in 1836, the 300-year old mission close to the modern Mexican border, is starting to show its age. “Increased visitor numbers do provide a valuable source of revenue,” says cultural director Warren Adams MRICS, of its 2.5 million annual visitors. “This also leads to a number of challenges.”

Singapore's Marina Bay Sands

There are three towers at the Marina Bay Sands and while many think the design is all about the enormous canoe-shaped roof garden that they support, its architect Moshe Safdie says the point is the spaces between that allow the sea to be glimpsed. “They wanted a museum piece for Singapore, and by that definition it had to be an iconic structure,” says Nicola Greenaway, of design company, NIKAU. “Marina Bay Sands really is our legacy now.”

St Louis’s The Wainwright

The building that almost never was, the Wainwright’s revolutionary steel-frame design was introduced after the original architects dropped out. The 10-storey block became an important stepping stone in the development of skyscrapers. “After the Wainwright, the potential for office and warehouse blocks to reach upward and express their structural grids clearly,” says Michael Allen of the National Building Arts Centre, “to announce that they were modern buildings, became realised widely, even when architects retained classical details.”

Stuttgart’s Weissenhof Estate

In 1920s Germany, some of the greatest names in architecture gathered to push their agenda with an exhibition of Modernism. Their designs not only reverberate today but survived Hitler’s ire. “Why do most architectural historians consider the Weissenhof so important?” says Dennis Doordan, professor of architecture. “The Nazis did not like Modernist architecture. In the long view of history, it helps your reputation whenever bad guys hate you.”